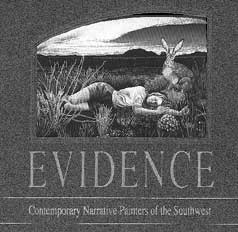

cover plate:

Therapeutic Alliance, 1987

In her painting “Therapeutic Alliance,” Lynn Randolph paints an allegorical and psy-choanalytic portrait. The rabbit standing over the sleeping woman is compositionally a contemporary response to the lion sniffing at the sleeping gypsy of Henri Rousseau’s famous painting. In Therapeutic Alliance, the radiant golden glow on the forehead also illuminates the inner ears of the attendant rabbit. A psychic link connects the rabbit to the woman and the golden glow (of the mind and the ear) relates to the universal symbol of becoming illuminated, of achieving enlightenment. Painted with meticulous realism, both figure and landscape are fused symbolically; in Lynn Randolph’s work, the landscape and sky, even as a backdrop and “stage” for the figures, have their own psychology; “if the landscape (earth) is understood as corporeal, then natural phenomena-lightning, dust devils, rain squalls–are the psychic forces that spiritually animate nature’s body”. In “Therapeutic Alliance,” the bank of clouds over the distant mountains arch back into the sky like an angel’s wing covering the sun.

• In “Time’s Journey,” Randolph has painted a powerful portrait of her mother, the four heads pirouetting into the sky are her mother’s portraits from youth to middle age. As an old woman, her mother sits cross-legged upon a celestial carpet which reflects the night sky. The desert landscape is painted with a crystalline fidelity–a nearly surreal clarity of plants and earth forms. In contemplating Times’ Journey, I could not help but be reminded of the Hopi and Navajo cultures of the desert southwest who thought of nature as a perfect organic structure and that we as humans–if we were to become ill or err in our humanness can physically and psychologically re-center ourselves through ritual sandpainting which acknowledges our presence in alignment with the powers of nature and spirits. Lynn Randolph’s mother in the painting Times Journey, can be seen as a symbol of feminine power and rejuvenation as well as one women’s progression through the stages of life.

• In an age of artmaking which supports, in part, illustrations of the denial of self, Randolph’s paintings offer testimony to what John Yau has refered to as self and body recognized “… it believes in the rhymes of autobiography and archetype. It posits that, like language, paint is both a highly mediated system and a constantly changing organism, both anonymous and personal, both a medium and a membrane that permits a recuperative and therefore imaginative response to the conflict between the public (surface) self and the personal (hidden) self.”

• In a statement for a recent exhibition, Jerry West wrote the following “…I hope to objectify, to expose, to disclose, to allow feelings and ideas to surface. I want also to address the mysterious aspect of human existence- the mythic quality of man and beast. The thoughts and memories themselves become enshrinements. This act of painting serves to release, to reveal, to focus and thereby become a nurturing, healing, and renewing process.”

• This statement verifies what the paintings by these narrative painters show: that their art is fundamentally an intense response to life. And in their positive as well as negative form of criticism, a plea for the return to humanistic issues.

_____________________________________________________________________

Evidence, Contemporary Narrative Painters of the Southwest exhbition catalogue, 1989, curated by Jim Edwards for the San Antonio Museum of Art. Catalogue essay by Jim Edwards.