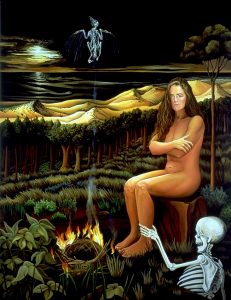

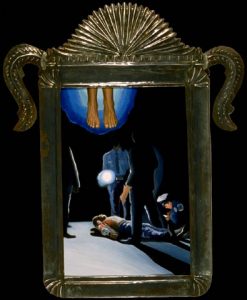

fig. 19

Presiding, 1991

Oil on canvas, 58 x 46 inches, Courtesy of the artist

Catalog essay from Millennial Myths: Paintings by Lynn Randolph, Arizona State University Art Museum, 1998

Lynn Randolph’s paintings infiltrate the fibers of my flesh and spirit. I mean this statement literally Randolph’s powerful figures protect, haunt, incite, soothe, instruct, and trouble me. Where I write, where I sleep, and where I eat, my daily life is suffused with the figures and stories that structure Randolph’s relentlessly narrative vision. Her metaphoric realism is, for me, a primer for the multilayered visual competence needed in the late twentieth century To see these paintings is to learn, in the words of Randolph’s engagement with the art historian Barbara Marie Stafford, how not to “become dumb watching” the visual pyrotechnics of our times.1 Prints of Randolph’s paintings appear in my books not as illustrations but as parts of arguments–as sites of meditation, dense feeling, and political reflection.

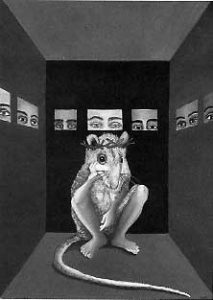

In my office at home, I write beneath a portrait of a mouse-human chimera that I experience as my sibling. My last book was revised literally under Randolph’s portrait of “The Laboratory/The Passion of OncoMouse,” 1994 (fig. 20).2 Set in the simultaneously global and parochial timescape of the end of the Second Christian Millennium, the book “Modesty_Witnesses@Seond_Millennium. FeMale-Man©_Meets_OncoMouse®” is about the figures, tools, and stories of technoscicnce as I have lived it in the United States in the 1990s. The biotechnological-biomcdical laboratory animal is one of the key figures inhabiting contemporary culture; Such figures take up and transform those they touch. They “body forth” meanings for communities: Randolph painted her trans-specific human-mouse hybrid in conversation with my chapter “Mice into Wormholes,” which examines the sticky threads ramifying from the natural-technical body of the world’s first patented animal–OncoMouse®, a breast cancer research model, produced by genetic engineering, that combines genes from different kinds of organisms: As a model, the transgenic mouse is both a metaphor and a tool that reconfigures biological knowledge, laboratory practice, property law, economic fortunes, and collective and personal hopes and fears.

In Randolph’s rendering, the white, female, breast- endowed, trans-specific cyborg creature is crowned with thorns: She is a female Christ figure, and her story is that of the Passion: She is a figure in the sacred-secular drama of technoscientific salvation history, encapsulating all of the disavowed links to Christian narrative that pervade U.S. scientific discourse. The laboratory animal is sacrificed; her suffering promises to relieve our own; she is a scapegoat and a surrogate. She bears our diseases, literally. Circled by peering eyes of many colors, she is the object of transnational technoscientific surveillance and scrutiny the center of a multi-hued optical drama. The bare-breasted hybrid mammal seems also to look at the viewer from inside a natural history diorama in a museum of natural- technical truth. Perhaps we also leer at her through a keyhole to a pornographic peep show; Her eyes lock with ours in a troubling and highly ambivalent gaze that, to me, suggests compassion, anger, reflection, pain, and curiosity; Her Passion transpires in a box that mimes the observation chambers of the laboratory, rooted in the dramas of the birth of modern science. OncoMouse is a figure both in secularized Christian salvation history and in the linked narratives of the Scientific Revolution and the New World Order–with their promises of progress, cures, profit, and if not eternal life, then at least life itself Randolph’s OncoMouse invites reflection on the terms and mechanisms of these less-than-innocent genetic stories of both nature and society. Her figure invites us to take up and reconfigure teehnoscientific tools and metaphors so we might practice the grammar of a mutated experimental way of life, one that does not issue in the New World Order, Inc.

fig. 20

The Laboratory / The

Passion of OncoMouse,

1994

Oil on Masonite

10 x 7 inches

Courtesy of Donna

Haraway, Santa Cruz,

California

I am part of the audience for Randolph’s work, certainly I enjoy her paintings; they give me visual and visceral pleasure. But also, beginning with Cyborg, 1989, she and I have found ourselves joined in a common project that is at once analytical, spiritual, metaphoric, and narrative. Randolph painted her Cyborg in conversation with my 1985 essay “A Manifesto for Cyborgs” providing a feminist portrait of the dangerous machine-human hybrids that populate our political, technological, corporeal, and imaginary landscapes; The painting maps the articulations among cosmos, animal, human, machine, and landscape through their recursive sidereal, bony, electronic, and geological skeletons; Their combinatorial logic is embodied; analysis is corporeal; The painting is replete with organs of touch and mediation, as well as with organs of vision; Direct in their gaze at the viewer, the eyes of both the woman and the white tigress shrouding her head and shoulders center the composition; The stylized DIP switches of the integrated circuit board on the human woman’s chest are devices that set the defaults in a form halfway between hard-wiring and software control–not unlike the X-ray-stripped, echoing, homologous bones of the feline paws and human hands; Beneath the woman’s fingers, a computer keyboard is jointed to the sandy desert-skeleton of the planet earth, a pyramid rising in the middle ground to her left. The spiraling skeleton of the Milky Way, our galaxy, appears on a screen behind the cyborg figure in three different graphic displays made possible by assorted high-technology visualizing apparatuses. The fourth square charts the gravity well of a black hole. Three tantalizing signs lace the space between the astronomical graphics: a tic-tac-toe game played with the European male and female astrological signs (Venus won); an equation from the mathematics of chaos, and a calculation found in Einstein’s theory of relativity. The math-ematics and games are logical skeletons in a painting intent on structural inquiry. The whole painting has the quality of a meditation device. The large cat is like a spirit animal. The woman, a Chinese student from Beijing residing in the United States in 1989, the year of the Tiananmen Square protests, figures the human, the universal, and the generic: a particular and recognizable person resonating with local and global conversations built into the skeleton of the earth and its galaxy in the late twentieth century. In this painting, she embodies the oxymoron of woman, “Third World” person, human, organism, communications technology, mathematician, writer, worker, engineer, scientist, spiritual guide, lover of the earth. This is the kind of “symbolic action” transnational feminisms have made legible. This is the kind of action that animates Randolph’s work for me.

fig. 21

Time’s Journey, 1987

Oil on canvas

58 x 46

Courtesy of the artist

“Cyborg” and “The Passion of OncoMouse” are important coordinates on the map of Randolph’s inquiry into technoscientine hybridity. These paintings highlight her immersion in processes of figuration and storytelling. But in order better to explore the spiraling story cycles built into Randolph’s work. I want to loop back, to begin again with another pair of paintings. “Time’s journey,” 1987 (fig. 21), is a life-cycle portrait of Randolph’s mother. A round-shouldered old woman dressed in a simple blue skirt and blouse, she is seated in a half-lotus position at the center of the picture. Her prayer rug is a thick, round, luscious blue and black carpet of the cosmos. Spiraling galaxies–typical of the celestial objects that recur constantly in Randolph’s iconography–lace the starry space that supports the curved body of the elder woman. Snaking down from the top of the composition in a sweeping curve, four faces mark the passage of a life from babyhood through mature middle age. The viewer of the painting looks from the Mexican side of the border toward Big Bend. The lavender-and lime-hued xeric plants of the desiccated desert in the foreground rise into a sere, sharp-peaked, rugged background–both elements reiterated throughout Randolph’s work. We have the ages of a particular woman here, one located in a specific, if capacious, landscape–not the ages of Universal Man in abstract time and space. This specific wise woman, whose body is threaded with the moments of her life, links the earth and the heavens into a single vivid timescape. This is the woman-centered vision that animates Randolph’s art to its core.

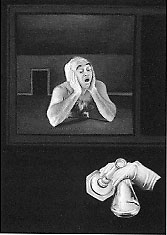

fig. 22

Fra Angelico

The Mocking of Christ

1440-41

Fresco

74 x 64.5 inches

Museo de San Marco

(cell 7), Florence, Italy

Like “Time’s Journey,” “Presiding,” 1991 (fig. 19), is a large canvas that deals with the passages of life and death. But unlike the recursive spiraling in “Time’s Journey” the motion in “Presiding” rises from bottom right to upper left-of-center in an ascending trajectory, emphasized by the smoke rising from a large burning nest at the feet of a nude, straight-backed, young, chestnut-haired woman seated with arms crossed over her breasts. Judge or witness–but mortal herself–the upright woman is presiding over the opening of a grave. The rectilinear, expulsive force of the painting is emphasized by the straight, thin tree trunk, topped with a coppery foliage, placed to the side of the woman. The bony hand of a human skeleton clutches her left ankle, while from the burning nest the birdlike skeleton of a compacted and fossilized archaeopteryx surges into the velvet-black night sky above a golden sunset / sunrise that is echoed by the gold sheen of beach dunes. The rising fossil is a fleshless phoenix, ambiguously promising life and death in the millennial last days of the painting. The portrait looks without flinching into the decade of the 1990s recorded in the present exhibition. I want the young woman of this painting, and the old mother tracing the moments of her life, to preside over my readings of Randolph’s “Millennial Myths.” 4 Graves open, indeed, but what issues from them is a matter for careful witness and judicious nurture.

1 grew up a Catholic in Colorado, and it is impossible to see Randolph’s images and not recall the complex physicality and spirituality of Mexican and Hispanic religious art that this Anglo Texas woman has inherited. Inter- laced in Randolph’s work with the currents of living artistic practice along the U.S.-Mexico border is the bodily spirituality that erupted in Italian late medieval and Renaissance visual art, especially the fresco cycles of men like Fra Angelico (see fig. 22). I spent a week in Florence in the summer of 1997, drowning in the reticulated imagery of the layer upon layer of stories laid down in the frescoes and paintings sedimented in that city. I cannot help but see Randolph’s millennial visions as part of the lineage of these symbolic, corporeal, technical, mystical art practices. Formal elements from Renaissance visual art and many devices and symbols from Mexican work pepper Randolph’s paintings. But, for me, the strongest evidence of her historical kinship with these two disparate forces is that her painting returns so often and so vigorously to the themes of suffering and hope. Her response, however is much more than symbolic: her mctaphoric realism is unmistakably political.

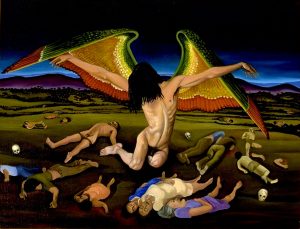

figs. 23

Merciful Angel, 1984

Oil on canvas

20 x 26 inches

Courtesy of the artist

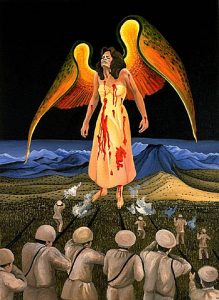

In the mid 1980s, Randolph painted several canvases of angels in the context of activism on Central American issues. She was an organizer of the Houston Area Artists’ Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America.5 A print of one of the paintings from the angel series hangs over my desk in my office at the University of California at Santa Cruz. “Merciful Angel,” 1984 (fig. 23), shows a compassionate nude male angel with cruciform wings and arms enfolding a field of corpses and skulls, a killing field resulting from the wars and military repressions tied to U.S. foreign policy. Profits from the sale of this print helped defray the costs of legal fees for Central American refugees. In Randolph’s paintings from the 1990s, angels continue to bear messages about war, suffering and injustice, all requiring a response. “U.S. Peace Plan,” 1990 (fig. 24), was painted in memory of the six Jesuit priests and their housekeeper who were murdered in El Salvador. In the center of the painting, an upright bloodied female angel with mottled Flemish-Renaissance wrings furling in death is executed by a firing squad of anonymous soldiers, backs to the viewer. Hot golds, reds, and oranges color the angel against a deep black sky, limpid blue mountains, and the sterile tans of the landscape and soldiers’ uniforms in the foreground. In “Angry Angels,” 1991, a bleeding androgynous figure with its head sagging toward earth is held aloft by two raging boy angels of military age, while bombs rain over the night sky of Baghdad, illuminating the spires of its mosques. The blue, red, and yellow wings flame with a fierce, angry energy.

fig. 24

U.S.Peace Plan, 1990

Oil on canvas

36 x 19 inches

Arizona State University

Art Museum

Angels protect, announce, and incite in more contexts than war, and I could not resist their solicitation in working out the arguments for “Modest_Witness@Second _Millenninm.” “Millennial Children,” 1992, helps me question the popular apocalyptic narratives of fin de siecle America without losing track of the all-too-literal devas- tations of land and soul around us. Stalked by African hunting dogs and mocked by a dancing medieval clown- devil with the leering face of George Bush for a stomach, two embracing girls kneel on the flaming ground outside the burning city ot Houston on the banks of an oil-polluted bayou. Facing the viewer, these millennial children ask if there can still be a future on this earth. Condors perch on the limbs of a blasted tree, its roots miming the bird-feet of the cavorting demon. Towers of a nuclear power plant loom in the background, and a stealth bomber dives toward the ground out of a lightning-scorched sky. Reds, blacks, and slashing yellows dominate the large canvas, relieved only by the sepia flesh and pastel dresses of the children and the greens of the not-yet-burned bushes.

The girls are whole and firm, flanked by diminutive guardian angels. Sober in their regard, the children have not been destroyed, but they are menaced by the apocalypse that engulfs the world. They are in the dangerous borderlands between reality and nightmare, between a comprehensive futurclessness that is only a dire possibility and the blasted futures of hundreds of millions of children that are a fierce reality now. These urban children in their polluted and abandoned cityscape call the viewer to account for both the stories and the actualities of the millennium.

fig. 25

A Way Out, 1991

Oil on Masonite

14.75 x 7 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Cityscapes do not dominate Randolph’s iconography, but when they appear, they are ferocious in their judgment. “Somnambulist Mall Walking,” 1995, shows us an immense, nightgown-clad, blond, zombielike woman with her arms outstretched. Oblivious to the troubles of Houston below, the space shuttle Explorer rises into space behind her. At the end of the millennium, “going where no man has gone before” seems a higher priority than walking through an evening cityscape free of violence and human devastation. Unmoored from her natural habitat–a suburban mall where culture, consciousness, and politics have been reworked into a theme park for the undead–the looming woman glides above the ruin of public urban culture. Children erupt from exploded buildings; bodies fall from the sky; a helicopter patrols the dangerous streets with its denuding spotlight trained on a knife fight below; armed and uniformed men sweep the streets. Perhaps at street level, we would see the drama portrayed in “A Way Out,” 1990 (flg. 25), which Randolph painted several months before Rodney King was savagely beaten by arresting officers in Los Angeles. Framed in the beaten tin of a Mexican retablo, “A Way Out” shows a prone,bleeding black man pinned under the pitiless lights held by erect, dark blue policemen. In the top center left, rising out of the frame of the picture, the lower legs of a brown- skinned human figure suggest another ascension. Is the prone man dead? Will he rise and bear witness to the truth above which the somnambulist from a gated subur ban community floats? Can the small retablo force the sleeping giant to wake?

The angelic messenger of the “Annunciation of the Second Coming,” 1996, which I used for the cover image of “Modest_Witness,” returns us to the technoscientific worlds of “Cyborg” and “The Passion of OncoMouse.” Our response to science and technology must be just as personal and just as structural as our response to war and the devastation of lands and cities. But if it is possible “simply” to oppose the latter outrages (in which science and technology are deeply involved), technoscience as a whole merits a much messier response. Randolph’s angel, painted according to Renaissance conventions except for her transparent wings, announces not the birth of Christ, but the warning–and also the promise–that life on earth is changing irrevocably. On the right side of the painting, a wormlike galaxy made of a giant DNA molecule echoes the angel’s message. This molecular genetic bioscape pre- sented in the vast proportions of a celestial starscape re- curs in many of Randolph’s paintings of the 1990s. Molecular dimensions, marked off in nanometers, recur-sively echo the orders of measure for astral vastness and questions for finite, mortal, historically specific human persons are coded into both sets of technoscientific scales. Striding through a stylized fifteenth-century Italian colonnade along the pathway of a computer circuit board, this classical and statuesque electronic Galatea carries in her troubling body both a threat and a promise. A “Wired goddess,” she is a matrix pregnant with the contradictions, emergencies, delusions, and hopes of colliding sociotech-nical worlds. No creator-Pygmalion will decide her fate; that is a task for human men and women in complex interdigitation with each other, their tools, and the other beings on earth and in space. Cyberutopia is a bad joke; cyberspace is not an option but a present responsibility. The child is already born.

In the early 1990s Randolph painted a series of nine small portraits, framed in worked tin in the style of nineteenth-century Mexican nichos, which she called “The Ilusas” (deluded women). These representations of women out of bounds (figs. 14, 15, 16), along with several other thematically related canvases in other sizes and styles. form a looping story cycle in thick conversation with both her angel paintings and her technoscientiftc figurations all exploring spirituality, power, excess, pain, embodiment, and knowledge. Each of the “Ilusas” paintings has at its center the single nude upper body or head of a woman with specific racial-ethnic markers (Japanese, Anglo, African-American, etc.). The “Ilusas” are like the paintings of saints in retablos. Each woman is given attributes of ecstatic, boundary-breaking speech and action. The women recall their seventeenth-century Mexican foremothers, condemned by the Inquisition as “las Ilusas” for their dangerous, disordered, independent discourse in public spaces. Their mystical experiences and disobedient bodies, ejecting blood, milk, and excrement, resignified the religious myths that had stigmatized them as prostitutes, widows, orphans, and estranged wives. Randolph presents her canvases in explicit conversation with writings in feminist theory, including work by Luce Irigaray, Jean Franco, Margaret Miles, and myself, as well as by Randolph’s husband, William Simon. Randolph’s unruly witnesses must remind us, too, of the uncounted homeless women–“ecstatic,” i.e., out of place in the most literal sense–who wander our cities today, also under the scrutiny of an inquisition in the service of the well-situated and privileged.

fig. 26

The Visitation, 1990

Oil on Masonite

10 x 7 inches

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

In this context, I remember Randolph’s painting of a homeless man whom she had photographed a year before his death. Framed in the same treated tin nichos as “The Ilusas” series, “Visitation,” 1990 (fig. 26), presents an old Tejano behind bars, in the company of a winged messenger –here not an angel but a singing, man-sized meadowlark whose vivid gold-yellow breast emphasizes the drab brown state-issued clothes of the human prisoner. Both figures are in a cage, and it is hard to imagine Mary’s Magnified! as the fruit of this visitation. Instead, in this confinement, “his soul magnifies the security of the comfortable, who disdain the lowliness of his presence.”8 A bird-sized man out of the bounds of scale, imprisoned in the established disorder that passes for normal in the last decade of the twentieth century, he demands a response proportionate to the outrage of his condition.

In “Modest _Wilness@,Second_Millennium,” I used one of Randolph’s disruptive women to frame a double argu-ment about the female body in technoscientific visual cul-ture and the terms of reproductive freedom for women linked in unequal transnational circuits of milk and diar-rhea in the struggles over infant death and breast feeding- “Venus, 1992, is a formal feminist intervention into the conventions of the female nude and her associated secre-tions and tools. Scrutinizing the standard line between pornography and art, Randolph writes:

This contemporary Venus is not a Goddess in the classical sense of a contained figure. She is an unruly woman, actively making a spectacle of herself. Queering Botticelli, leaking, projecting, shooting, secreting milk, transgressing the boundaries of her body. Hundreds of years have passed and we are still engaged in a struggle for the inter- pretive power over our bodies in a society where they are marked as a battleground by the church and the state in legal and medical skirmishes.9

This frontal nude portrait of a “woman of color” marks one of the many risks Randolph takes in the looping story cycles other female figurations. Her representational technique, content-rich narrative, and symbolic material put her into argument with the formalist orthodoxies of the elite art world. And her insistent interrogation of culturally and historically located, as well as racially and sexually explicit, bodies places her at the heart of explosive feminist debates. What does it mean for an Anglo woman to depict a Chicana-Mexicana for her own reading of the Virgin of Guadalupe (“La Mestizo Cosmica”)? Can a white woman, no matter what her intentions and careful framings, paint nude women of color without reproducing the appro

Three paintings that I see in deep conversation with the “Ilusas” are “La Mestiza Cosmica,” “So?” and “Alone in the Wetlands of Desire.” Each of these paintings addresses the dilemmas I outlined above in very different ways.

“La Mestizo Cosmica,” 1992 (fig. 27), gives us a modern Virgin of Guadalupe, a figure Randolph describes as:

…related to the Virgin of the Apocalypse who crushes the serpent and is in possession of the heavens, the place from which she protects her chosen people. She is still revered in Mexico today as she is a symbol of rebellion against the rich upper and middle class. She unites races and medi- ates between humans and the divine, the natural and the technological. In my painting a Mestiza stands with one foot in Texas and one foot in Mexico. She is taming a dia- mond-back rattlesnake with one hand and manipulating the Hubble telescope with another.10

fig. 27

La Mestiza Cosmica

(detail), 1992

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 inches

Courtesy of the artist

“La Mestizo Cosmica” is the kind of modest witness coming into existence at the end of the Second Christian Millennium, when what can count as freedom, justice, knowledge, and skill are again very much at stake in the mutated experimental way of life. Randolph’s Mestiza straddles the borders that are even now being redrawn by both thefree trade agreements of the New World Order, Inc., and the fierce anti-immigrant politics of the rich nations against poor and non-white peoples. Technoseicnce is fundamental to the dense flows of capital, people, know-how, machines, genes, and much more across these borders. “La Mestiza Cosmica” is historically specific, located in a particular time, place, and body; she is, therefore, a figure representing the kind of global consciousness a modest witness should cultivate. The rattlesnake and the four hands suggest a mode of con-sciousness called the Coatlique state, associated with an Aztec goddess, as theorized by Gloria Anzaldua.11 Not unlike Anzaldua, who maintains a necessarily eclectic altar on her computer, Randolph’s Mestiza joins the snake and the Hubble telescope to demonstrate the kind of vision needed in the New World Order. This woman is a scientist and a wise person situated on the planet earth and in space, a position underscoring the technoscientincally mediated globalization that is transforming chances for life and death for all of earth’s inhabitants. Randolph risks the imagery of the New Age and the charge of appropriation across races and cultures to locate her figure so that the parts of her body are in potent physical and symbolic zones. Like her contemporary model on the Texas-Mexican border, “La Mestiza Cosmica” is indigenous to these millennial border-lands. Able to establish crucial matters of fact, she is a retooled modest witness to that border’s present transformations.

“So?,” 1993 (fig. 1), presents a young African-American woman seated on an open vulva like flower with orange- red tissues that reminded me of the soft parts of a marine mollusk. The mollusc a creature whose siphons extend from one medium into another so that the animal may eat and breathe, is like the woman–a liminal being at the limit of multiple dangerous border states. She is under the earth entangled in the roots of a tree of life, while her hands are lifted in a questioning gesture toward the bright edge of earth and sky above. The time could be sunrise or sunset, and the woman herself is naked, situated at the join between the ravages of history and a threatened, but still open, future. Like the woman in “Venus,” this is not one of Botticelli’s earth-sea nymphs, but a being rooted in quite different histories and inquiries into power and knowl-edge; In the loops of the tree roots; five stories cling like nodules; these stories must be built into memory if the fu- ture is not to be nourished by lies. In one node, a figure is lynched by the Ku Klux Klan; in another, an African woman with a child on her back bends over parched agri- cultural fields. In the third, a Black preacher piouslv cau-tions silence about outrages the woman knows well. In the next nodule, a white-handed policeman holds a gun in the mouth of an African-American man, and in the final oval, Anita Hill testifies before the pig-headed Senate Judiciary Committee in the confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court. The nude figure is a whole woman, not a body part. Her eyes call the viewer to critical consciousness on many levels–the conventions of the female nude in art; the history of representation of women of color, in particular; and the specific conditions of labor, sexuality, gender, speech, and credibility for people of African descent in the “new world.” The tree of life is not dead in this landscape but reticulated with roots of pain. Still, the woman refuses to be another suffering servant hanged on the tree of Jesse in either a religious or a secular version of Christian salvation history. Her “so?” insists on a different response. Read her with the large canvas of “Sky Walker Biding Through,” 1994, showing a powerful, big-breasted woman thrusting aside the cosmic obstacles in her path to stride through space with a compelling earthly presence. Then read both of these figures with the strong middle-aged blond woman in “Interpellating,” 1994 (fig. 28), who is ripping apart the entrapping silk fibers of a giant spider web, perhaps “interrupting the hype-webs of cyberspace by being physically there.” 12

Many of Randolph’s paintings explore a womn in the solitude of her own company or in the company of natural andartifactual non-human others. These women alone are potent beings, not fragments waiting for completion. The human figure in its relentless specificity pervades Randolph’s work, but the female nude presents special problems for a feminist artist alert to the visual exploitation of women’s bodies. Randolph avoided painting female nudes for several years, but prohibition did not exorcise the demons of a complex history–of the personal psyche, of Western art, of patriarchy, or of racism. “Alone in the Wetlands of Desire,” 1993, confronts these matters with risk and with hope. In the dreamspace that Randolph sees as existing before and after patriarchy, before and after conquest; a nude Iranian-American woman lies on a bed of melting ice set in a dense forest. Her buttocks are toward the viewer, but there is no invitation for a missing lover to join her or to consume her visually. She lies alone as a complete figure, in a space of desire that encompasses the primal opposites of the setting. Are the contradictions of history culpably elided and the violences of representation illegitimately suspended? Or is this dream sustaining a needed vision of elsewhere, where a particular woman’s desire, whole in itself, must endure if she is to tear apart the entangling spider webs of the informatics of domination, wake the somnambulists mall walking toward the millen-nium, and bide through on a real earth?

I want to end by looping back through Randolph’s story cycles of technoscience, where our engagement with each other’s work began. If the marked female nude is “forbidden” to the unmarked feminist artist–and so must be faced by a border painter whose mother sits watching her from Big Bend–then the pleasures and dangers of technoscience are also forbidden to the woman, who could not be part of the masculine clerical culture of secular-sacred knowledge issuing from the machines and laboratories of transnational modernity. And so, the artist who sees a rattlesnake and a Hubble telescope in the hands of a young Chicana cannot not cross the raced and gcndered border that guards powerful knowledge and skill. I will order my final reading of Randolph’s story cycle under the sign of OncoMouse and the Cyborg–one a human-animal chimera, the other a human-machine hybrid, each a sister to the other and to me. It’s all in the family in the borderlands of millennial myths. I imagine that these spliced beings are the viewers of the last three paintings, all large and dramatic, that I will address: “Yesterday Inventing Tomorrow Today,” “Managed Care,” and “Transfusions.”

fig. 28

Interpellating, 1994

Oil on casonite

30 x 24 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The dead hand engineering the germ of the future is the theme of “Yesterday Inventing Tomorrow Today,” 1996. Three white men and a white woman, all clothed, inhabit a sere black knowledge-manufacturing chamber. My spliced viewers get their temporal and bodily bearings from a human skull on a stand in the foreground and, in the background, from a mid-body sonographic image of a pregnant woman and a transverse MRI scan of a human brain. These are the chief diagnostic icons of popular conceptions of biomedicine, past and future. A large DNA molecule snakes from behind a man in the center of the composition holding a tiny gemlike germinal object–a microprocessor chip. The luminous double helix, master molecule of genetic ideology, spirals out of the window and into its proper celestial sphere. A red-shirted man to the left rear of center is seated at a keyboard from which rises a small, gold-lit tree with a gleaming yellow pear englobing a magic seed. I read here a subtle joke about the tree of knowledge that grew in a much more luscious garden of Eden in a sibling origin story. The interface of informatics and biologies in writing the codes of life is unmistakable. The technoscientific objects seem like the attributes of a saint by which the viewer could identify the drama depicted in medieval art. We are in a morality play of a rather skeptical sort. The chip, gene, seed, fetus, and brain all mark stories origin and potency in transnational technoscience; they are the attributes of the saint called Progress. The self-serious iconography makes the Cyborg and OncoMouse laugh. This is their family’s primal scene, after all, am they are disobedient offspring with a great deal of life in them. To the right of the composition, a middle-aged blond woman stands with her hand massaging her tired neck; she is pensive, perhaps bored, maybe worried, but definitely not worshipful in this secular-sacred theater of time. She reminds the hybrid viewers that technoscience may be full of fine surprises and deep interest, but its pretensions to creation are a dangerous–or maybe just a boring–sham. The death’s head skull ends up as a reassuring reminder that all that is gold returns to fertilizing dust. The upright woman of “Presiding” knows that mortality, not transcendence, is a friend. Without mortality, we would not care much about suffering, or about desire and pleasure; we, with DNA, could be raptured out of thi body onto an astral plane.

figs. 29

Managed Care (detail),

1996

Oil on canvas

60 x 48 inches

Courtesy of the artist

“Managed Care,” 1996, is an unambiguously angry paint-ing, done in the aftermath of the defeat of comprehensive national health insurance in the United States at the beginning of the 1990s with the subsequent profit-driven development of corporate health maintenance organizations. The body in pain dominates the composition. Once again, we are in a tcchnoscientific chamber, this time looking down on a screaming adult Anglo with white hair, stark naked on a hospital bed and gnawed by the mice famous to biomedical researchers and to readers of the science news in the daily paper. OncoMouse takes particular notice of the sorry fate of her rodent kin, engineered like herself to be models for the relief of human disease. A white mouse with a human ear growing out of its back and a naked mouse important to cancer and immune-system research snack on the hapless gentleman. Disembodied doctor-hands with syringes, forceps, flasks, and test tubes surround the suffering figure, and diagnostic films line the walls like the Great Art they are taken to be in advertising, courtrooms, television, conferences, laboratories, and clinics: A man reminiscent of the figure in Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” 1893, peers from the back of the painting into this chamber of horrors that should be a healing room (fig. 29). The man is the same person as the figure on the hospital bed: he is seeing himself in this theater of pain; The black field of the painting is punctuated by the disordered stark white sheets, the yellow-pink flesh of the patient, and the ultraviolet glow of the diagnostic scans; The promise of managed care becomes the reality of the sick body managed for profit. OncoMouse, in particular, is not amused.

After helping to organize a grassroots meeting for comprehensive health insurance and a research agenda at- tuned to human and environmental needs–a meeting that brings patients, students, artists, scientists, clinicians, street people, and policy-makers together–OncoMouse and Cyborg leave the hospital and head for the movies. There, the undead make a more ambiguous and interesting technoscientific promise than that dramatized in the primal scenes of lab and hospital just visited. “Transfusions,” 1995, has haunted me since Randolph painted it in conversation with a paper I did on racial categories in twentieth-century biology called “Universal Donors in a Vampire Culture: It’s All in the Family.”13 A print of Randolph’s vampire story sits on a shelf above my bed, where it can inform my dreams of kinship in a reworked primal scene.

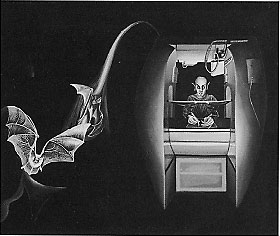

fig. 30

Transfusions (detail),

1995

Oil on masonite

48 x 60 inches

Courtesy of the artist

In an unrelieved black space, a blue-clad dancer’s body lies prone on a stark white gurney, her neck penetrated by a vampire bat whose wing vessels pulse with her red blood. A transfusion bag on a medical stand ties into the circulation of the woman and the bat, which is linked in swirling time-lapse photographic repetitions to the tele-operator chamber in the top right-hand quadrant of the painting (fig. 30). Inside the chamber and operating its controls is the rat- toothed figure of Count Graf Olock (Max Schreck) from “Nosferatii: The Vampire, F.W. Murnau’s 1922 German Expressionist silent film that was the first vampire movie.14 The fingernails on the hand of the mad doctor-vampire are clawed, and the chamber swathed in the sterilizing light of blues, purples, and ultraviolets. The black field of the painting is transected by the white of the slab and punctuated by the reticulatioi and pools of red blood. The Surrealist traffic of informatics and biologies in the circulating fluids of the cables governed by the joy sticks of the remote control machine, the dancing bats, and the prone woman infuse the visual field.

Remembering the toxic cocktail of organicism, anti-Semitism, anti-capitalism, and anti-intellectualism that percolates through vampire stories, I cannot see Randolph’s painting as a simple affirmation of the woman and an indictment of the techno-vampire. The painting is disturbing, but not in any simple way. One of my responses to “Transfusions” is to feel myself in the circuit of fluid exchange in the drama, joined to the currents that pulse through the bodies of Cyborg and OncoMouse, not so far from the wells of milk, excrement, and blood known to the “Ilusas.” Drawing on her practice of metaphoric realism, and in conversation with cyborg Surrealism, Ran-dolph uses the vampire-cyborg mythology to interrogate the undead psychoanalytic, spiritual, technical, and bodily zones where biomedicine, information technology, and the techno-organic stories of kinship implode. This is the kinship exchange system where gender, race, and species–human, animal, and machine–are all at stake.

Randolph’s vampire story is neither denunciatory nor celebratory of technoscience; Rather, her paintings inhabit the dreams and nightmares of technoscientific culture to interrogate its stories, to taste its pleasures and dangers, to remember and recollect specific bodies–literally, as always. There is no reductive ideology in Randolph’s millennial myths; instead, the paintings make the viewer ask whose millennium is this, whose story takes flesh here, whose borders are at stake? Randolph’s border art is hostile to technophilic euphoria, to New Age rapture,to self-satisfied political critique, or to any other device for evading the irreducible contradictions of earthly histories. That is the message that Randolph’s angels and other winged beings deliver. And that seems to me precisely the right discipline for learning how not to “become dumb seeing.” The woman who poses the question in “So?” expects a response.

NOTES

1 Lynn Randolph, “Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Technoangels: A Series ot Spectacles,” paper presented at The Center for the Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, April 23, 1996.

2 Donna J. Haraway, “Modest_Witness@Second_Millen-nium.” FeMaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse (New York: Routledge, 1997).

The title is to be read as an email address.

3 Donna J. Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs,” Socialist Re- view, no. 80 (1985): 65-108. Lynn Randolph, “A Return to Alien Roots,” Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, Spring Solo Exhibition, 1990. Randolph’s “Cyborg” is the cover image for Donna J. Haraway’s, “Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991).

4 “Millennial Myths: Paintings by Lvnn Randolph,” solo exhi- bition at theAriona State University Art Museum, February 27- May 24, 1998.

5 Randolph also helped organize to the Women’s Action Coalition (WAC) to greet the 1992 Republican Convention in Houston. They drowned out Operation Rescue during the convention with their erotic, anti-military rhythms. She played with the WAC drum corps, which has had a tine afterlife. A reconstituted Houston drum corps, “The Ilusas,” practiced regularly at St. Stephens Epis- copal Church. In 1996, the drum corps turned out to welcome Newt Gingrich to Houston on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.

6 “Angry Angels,” 1991, oil on masonite, lO.5 x 7.5 in. Courtesy of the artist.

7 From Randolph’s description in her “Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Technoangels.”

8 I paraphrase Mary’s announcement of her pregnancy to her cousin Elizabeth, “My soul magnilies the Lord,…for he has re- garded the low estate of his handmaiden.” Luke 1:46-48 (Revised Standard Bible).

9 Lynn Randolph, “The Ilusas (deluded women): Representa- tions of women who are out of bounds,” paper and slide presen- tation at the Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 30, 1993.

10 Ibid.

11 Gloria Anzaldua, “Borderlands / La Frontera” (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute, 1987).

12 Lynn Randolph to Donna Haraway, personal correspondence, Jan. 29,1995.

13 Donna J. Haraway, in “Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium,” pp. 213-65.

14 “Nosferatu” was loosely based on Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, “Drucula,” the dominant source of the twentieth-century image of the vampire in popular culture. The anti-Semitic, sexualized swamp of images in which earlv vampire stones flourished silently soaked the tissues of”Nosferatu,” from the rat-toothed Count Orlock who controlled the rodents thai brought plague to Bremen; to the word “Nosferatu,” derived from an old Slavonic word tied to the concept of carrying the plague; to the illicit sale of German prop- erty, signifying the “foreign” threat to an “innocent” German town, a danger mediated by money trafficking; to the mobiliza- tion of the “Volk” to chase the monster; to the virgin of pure heart who must save the people by her sacrifice. See Ken Gekler, “Read- ing the Vampire” (New York: Routledge, 1994).