Selected Presentations

- The Soul’s Eye: Art in the life of people with terminal illness

The Fourth Annual Symposium "The Collective Soul", January 30 -31, 2015, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center - Unspoken Stories

Houston Seminar, February 2013 - Modest Witness: A Collaboration with Donna Haraway, 2009

- Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Techno-Angels: A Series of Spectacles

Center for the Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, 1996 and Arizona State University, February 1998 - Between Cultural Eras: The Effects of Postmodern Thinking on the Modernist Concept of Regionalism

College Art Association 83rd Annual Conference, San Antonio, Texas, January, 1995 - The Ilusas (deluded women): Representations of women who are out of bounds

Presentation for the Society of Institute Fellows at the Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 1993 - Secular Uses of Traditional Religious Images in a Postmodern Society

Women's Caucus for Art, February 1991

Modest Witness: A Collaboration with Donna Haraway, 2009

by Lynn Randolph

When I read Donna Haraway’s Manifesto for Cyborgs in 1989, I was intrigued and inspired. Here was a piece that resonated with my political, feminist and moral values. Haraway was getting up close, magnifying and focusing on science, technology and socialist-feminism while contesting the “old world order.” Her work brought to mind Robert Hooks’ first look through a microscope and William Blake’s painting of a flea. Donna Haraway was creating new ways to approach Nature/Culture. She insisted that we find new relationships to nature besides possession and reflection, and that we converse with wily coyotes. We are not innocent players and we must assume responsibility for constructing alternative cultures within our own specific environment. It’s a curiously hopeful view. Haraway drew on metaphors and narratives and deconstructed myths to envision the alternatives. She recommended blasphemy, irony and humor as the means toward a comprehensive subversion of the cultural practices surrounding science, technology, and socialist-feminism as she dismantled and reassembled their codes. She offered pleasure, pleasure in becoming competent in the use of new techno-scientific tools and the opportunities they presented. Some of her tools, particularly the factual detail and heightened metaphoric language, as well as the use of narratives, were a central part of my repertoire.

The figure she proposed for this salvation was a cyborg, a hybrid of machines and organisms. The cyborg could contain incompatible truths. The cyborg might change our perceptions of reality and alter old beliefs. Cyborgs are both real and fictional. We are all cyborgs in that we rely on various chemicals and communication technologies to see us through each day.

Along with the cyborg figure, Haraway pointed to contemporary science fiction writers such as Octavia Butler and John Varley, who use techno-surreal cosmic scapes, vehicles, and time warps to gain perspective. Octavia Butler contests with the borders and boundaries of race, class, and gender. Butler and Varley have been part of the scarce contingent of artists who offer a new or different vision in a culture caught up in simulations and appropriations and the linear patterns that modernism promoted. Haraway recognized that they were creating speculative futures informed by transnational technoscience and that they had opened up a space where they could intervene and tinker with critical social, political, and ethical concepts. In Butler’s Xenogenesis Trilogy, her “aliens” view the earth from deep outer space. The Oankali and Ooloi (the Aliens) know we are inferior because we are eaten up with a bad case of the “hierarchies.” They are gene traders and think our cancer cells could be useful, so during a period of nuclear and ecological annihilation on Earth, they capture a group of humans and “pod” them. The rescued and awakening earthlings have to confront totally other creatures and begin to renegotiate life. In their desire to survive, the humans overcome the difficulty in mating in a tri-partite scheme with physically repugnant aliens. These strategies fit well with my surrealist tendencies to juxtapose images of real people, places and things into potent fusions and new couplings, to subvert the old order, transgress boundaries, make the marginal central, dream others dreams and re-code the representations of woman in U.S. cultural life.

In 1989 I left Houston (where I still reside) for a year in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I had been given a painting fellowship at the Bunting Institute (now the Radcliffe Center for Advanced Studies) for my project, a series of paintings entitled ” A Return to Alien Roots: Painting Outside Mainstream Western Culture.” Just before leaving Houston, I read Haraway’s manifesto. When I arrived at the institute, I participated in many discussions of the piece with the Bunting Fellows. Several found it baffling and the writing difficult; others like myself were completely knocked out. Many of the colloquia given that year mentioned this article. Haraway gave a presentation at Harvard that fall. Within the university there was both great excitement about and great resistance to her approach.

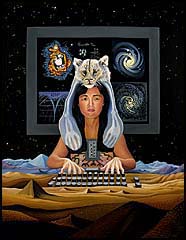

Haraway’s description of Asian women with nimble fingers, working in enterprise zones for very little remuneration stuck in my head. I had recently met a young Chinese woman, Grace Li, who was one of my late husband’s sociology students at the University of Houston. We were particularly concerned for her that spring because her parents lived only a few miles from Tiananmen Square. I asked Grace if she would pose for me and she agreed. Personal computers were still relatively young in the technological revolution and I could clearly see their potential for empowerment.

So I placed my human-computer/artist/writer/shamans/scientist in the center and on the horizon line of a new canvas. I put the DIPswitches of the computer board on her chest as if it were a part of her dress. A giant keyboard sits in front of her and her hands are poised to play with the cosmos, words, games, images, and unlimited interactions and activities. She can do anything. The computer screen in the night sky offers examples. There are three images that graphically display different aspects of the same galaxy, using new high-technological imaging devices. Another panel exhibits a diagram of a gravity well. The central panel offers mathematical formulas, one from Einstein and the other a calculation found in chaos theory. In the same panel a game of tic-tac-toe has been played using the symbols for male and female and the woman has won. The foreground is a historical desert plain replete with pyramids, implying that the cyborg can roam across histories and civilizations and incorporate them into her life and work. Finally I placed the shamanic headdress of a white tigress spirit on her head and arms. The paws and limbs of the tigress reveal its skeleton. They both look directly at the viewer. The underlying intent was to create a figure that could visually do what Haraway was describing as the potential for re-figuring our consciousness.

So I placed my human-computer/artist/writer/shamans/scientist in the center and on the horizon line of a new canvas. I put the DIPswitches of the computer board on her chest as if it were a part of her dress. A giant keyboard sits in front of her and her hands are poised to play with the cosmos, words, games, images, and unlimited interactions and activities. She can do anything. The computer screen in the night sky offers examples. There are three images that graphically display different aspects of the same galaxy, using new high-technological imaging devices. Another panel exhibits a diagram of a gravity well. The central panel offers mathematical formulas, one from Einstein and the other a calculation found in chaos theory. In the same panel a game of tic-tac-toe has been played using the symbols for male and female and the woman has won. The foreground is a historical desert plain replete with pyramids, implying that the cyborg can roam across histories and civilizations and incorporate them into her life and work. Finally I placed the shamanic headdress of a white tigress spirit on her head and arms. The paws and limbs of the tigress reveal its skeleton. They both look directly at the viewer. The underlying intent was to create a figure that could visually do what Haraway was describing as the potential for re-figuring our consciousness.

Shortly after completing my cyborg painting I sent a slide to Donna Haraway. She had recently begun teaching at the University of California at Santa Cruz, History of Consciousness program. She called me at the Bunting Institute to ask if she could use the Cyborg painting for the cover of her new book Simians ,Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. She explained that it had already gone to press and that there would be no accompanying text. I was delighted. We talked about the painting and I felt that she completely understood my effort. She asked to see other work that I’d done and I began regularly sending her slides of completed work. A year or so later she wrote asking if she could use a black-and-white print of the Cyborg painting as the final image in her essay, “The Promises of Monsters.”1 Her essay included a description of the painting. She put into words everything I was trying to articulate in the painting. She made me aware of the way I had used skeletons as an organizing tool. “The painting maps the articulations among many cosmos, animal, human, machine, and landscape in their recursive sidereal, bony, electronic, and geological skeletons,” she wrote, “The mathematics and the games are like logical skeletons.” Haraway’s description helped me talk about the painting when I presented it to others. Our dance had begun.

“The Promises of Monsters” expanded my thinking. At that moment the cultural landscape seemed flat. With few exceptions, cultural workers were creating a mosaic of simulations of the past. I was attracted to Haraway’s attempt to find a different space, a place from elsewhere, where the sacred images of commodity production and the deadly images of the same were no longer present. This is not a fantasy place, but one that is present and available and where we might find new meanings and different values.

I am an imagist. I believe that the closest we ever get to a provisional “truth” is through metaphors and I think of my paintings as metaphoric realism. More than forty years ago I set a course in opposition to mainstream Western painting, resisting modernism’s nearly exclusive concern for the sequencing of differences in linear illusions of progress (the avant garde) and formalism (art about art). I rebelled when abstraction triumphed over the figure and when, in pursuit of the sublime, empty universalism (transcendentalism) was elevated over earthly evidences of the human spirit. The art world today is much more pluralistic, but it seems to me to be commodity–driven and committed to aesthetisizing the banal. I remain committed to painting particular people, places and things. In going from the specific physical object to the metaphysical, via the metaphorical arrangements and juxtapositions of objects, the content or subject will bind itself to the structure and forms in which it occurs.

Metaphoric realism is a literary term and describes a kind of text. I use the word real to mean resembling the real, feeling real, not naturalistic. Images can often do more than words, and more efficiently. Images can constitute metaphors that can be read/interpreted. There are antecedents for this kind of reading in pre-modern art in Native American sand paintings, Hindu religious miniatures, and nineteenth-century Mexican retablos, to name a few. This language of images requires a different kind of participation from the viewer than much of modern art. It asks to be interpreted or apprehended, not just appreciated. Visual metaphors are hybrids, they call upon the beholder to combine and synthesize experience that analysis has fragmented or dissected. Metaphors can be a powerful means of communicating the rationally ungraspable. They are both a mode of persuasion and a catalyst for change. However, we should never shrink from asking: Whose metaphors?

The connection between visible surface and invisible depth is crucial, particularly for me as a painter. The inarticulate relationships of interior to exterior, idea to form, private pathos to public patterns, from local events to global ramifications, and the sacred metaphors that draw on outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace, all remind us that visual and verbal skills and critical thinking are necessary to artist and viewer alike.

I like the idea of engagement and being in informed touch with multiple fields of knowledge. Underneath a work of art are traces of what shaped it: the artist’s values, knowledge, psychological make up and spiritual force. Art, allied with its various sources, can serve as a vibrant shaper of thought.

The connection I felt with Haraway’s work was not just limited to her exciting metaphors and narratives and her ideas. It was strongly linked to her process of thinking and writing. Her use of hypertext as a metaphor for reading and writing practices relates to my own way of making the connections that form my paintings2.

“Hypertext,” she writes, “both represents and forges webs of relationships. Hypertext actively produces consciousness of the objects it constitutes.”… “Hypertext is a computer mediated indexing apparatus that allows one to craft and follow many bushes of connections among the variables internal to a category, … Helping users hold things in material-symbolic-psychic connection, hypertext is an instrument for reconstructing common sense about relatedness…Perhaps most important, hypertext delineates possible paths of action in a world for which it serves simultaneously as a tool and metaphor. Making connections is the essence of hypertext. Hypertext can inflect our ways of writing fiction, conducting scholarship, and building consequential networks in the world of humans and non-humans.”(2)

The conversation with Donna Haraway continued. In 1990 she wrote of our creative relationship, “Somehow we ended up with cross-linked religious, political, and psychological imagery!” I whole-heartedly agreed. In 1991 she wrote “Where did you get such a biologic imagination?”

During the early 1990s I was working on a series of paintings I called the Ilusas (the deluded women). They are representations of women who are out of bounds. I was interested in the questions about female sexuality and pornography that were being contested and I wanted to add spirituality to the equation. I was grounded by the work of my late husband William Simon (see Postmodern Sexualities 1996)3 as well as Jessica Benjamin’s text The Bonds of Love,4 1988 and Margaret Miles’ book Carnal Knowing5 1989. Luce Irigaray’s piece “La Mysterique” in Speculum of the Other Woman6 1985 was particularly exciting to me. The first-person accounts of the mystic saints may have been the earliest recorded by women of their spiritual /sexual experiences.

One of the paintings to emerge out of all this reading, thinking, and visioning is entitled Venus. It is an image of a contemporary woman (and friend) who is pregnant. She is not a goddess in the classical sense of a contained figure. She is an unruly woman, actively making a spectacle of herself, queering Botticelli, leaking, projecting, shooting, milk, transgressing the boundaries of her body. Botticelli’s shell has been turned upside down, and it is raining. Hundreds of years have passed since Botticelli painted his Venus and we are still engaged in a struggle for interpretive power over our bodies in a society where they are marked as a battleground by the church and state in legal and medical skirmishes.7 I sent Haraway a slide of Venus and she included it in Modest Witness. In the essay she wrote for an exhibition of my work at Arizona State University Art Museum,8 she stated: “In Modest Witness, I used one of Randolph’s descriptive women to frame a double argument about the female body in technoscientific visual culture and the terms of reproductive freedom for woman linked in unequal transnational circuits of milk and diarrhea in the struggles over infant death and breast feeding.”

One of the paintings to emerge out of all this reading, thinking, and visioning is entitled Venus. It is an image of a contemporary woman (and friend) who is pregnant. She is not a goddess in the classical sense of a contained figure. She is an unruly woman, actively making a spectacle of herself, queering Botticelli, leaking, projecting, shooting, milk, transgressing the boundaries of her body. Botticelli’s shell has been turned upside down, and it is raining. Hundreds of years have passed since Botticelli painted his Venus and we are still engaged in a struggle for interpretive power over our bodies in a society where they are marked as a battleground by the church and state in legal and medical skirmishes.7 I sent Haraway a slide of Venus and she included it in Modest Witness. In the essay she wrote for an exhibition of my work at Arizona State University Art Museum,8 she stated: “In Modest Witness, I used one of Randolph’s descriptive women to frame a double argument about the female body in technoscientific visual culture and the terms of reproductive freedom for woman linked in unequal transnational circuits of milk and diarrhea in the struggles over infant death and breast feeding.”

After completing about ten of these small Ilusas paintings that dealt mostly with spiritual/erotic constructions, I started to enlarge their context to include more social and political concerns. Technoscience became a dominant theme. I felt as though I were living with Donna Haraway’s work and interests, and they had became a part of me. In 1992 I painted one I call La Mestiza Cosmica, a version of the Virgin of Guadalupe who is not represented as a mother. Rather she is related to the Virgin of the Apocalypse, who crushes the serpent and possesses the heavens, the place from which she protects her chosen people. She is still revered in Mexico as a symbol of rebellion against the upper classes. She unites races and mediates between humans and the divine, the national and the technological. In my painting, a Mestiza stands with one foot in Texas and one foot in Mexico. Although she doesn’t describe any particular text, she was born from the belly of Donna Haraway’s pregnant monsters. The figure in La Mestiza Cosmica is taming a diamond-back rattlesnake with one hand and manipulating the Hubble telescope with the other. There are two additional hands coming out of the cosmos and the four together echo a giant sculpted image of the Aztec goddess Coatilique. She seems to me more relevant today as we deal more intently with borders, fences, free trade, the deaths of many (some say over 300) young women working in the maquiladoras and stores and restaurants that proliferated in Juarez after the NAFTA agreement. My Mestiza knows how to straddle the border, tame the rattlesnakes, and enjoys manipulating technoscientific apparatuses.

After completing about ten of these small Ilusas paintings that dealt mostly with spiritual/erotic constructions, I started to enlarge their context to include more social and political concerns. Technoscience became a dominant theme. I felt as though I were living with Donna Haraway’s work and interests, and they had became a part of me. In 1992 I painted one I call La Mestiza Cosmica, a version of the Virgin of Guadalupe who is not represented as a mother. Rather she is related to the Virgin of the Apocalypse, who crushes the serpent and possesses the heavens, the place from which she protects her chosen people. She is still revered in Mexico as a symbol of rebellion against the upper classes. She unites races and mediates between humans and the divine, the national and the technological. In my painting, a Mestiza stands with one foot in Texas and one foot in Mexico. Although she doesn’t describe any particular text, she was born from the belly of Donna Haraway’s pregnant monsters. The figure in La Mestiza Cosmica is taming a diamond-back rattlesnake with one hand and manipulating the Hubble telescope with the other. There are two additional hands coming out of the cosmos and the four together echo a giant sculpted image of the Aztec goddess Coatilique. She seems to me more relevant today as we deal more intently with borders, fences, free trade, the deaths of many (some say over 300) young women working in the maquiladoras and stores and restaurants that proliferated in Juarez after the NAFTA agreement. My Mestiza knows how to straddle the border, tame the rattlesnakes, and enjoys manipulating technoscientific apparatuses.

In 1994 Haraway sent me a draft of “Mice into Wormholes: A Techno-science Fugue in Two Parts.”9 It was an implosion of science and technology loaded with images. I loved the visual possibilities of what she referred to as “startling hybrids of the human and unhuman in technoscience. “ Shaping technoscience is a high stakes game, she wrote, “a form of life.” I was captivated by her description of the herbicide-resistant crops and genetically engineered plants. It was hard to resist combining a tomato and a flounder in a painting. But the image that lingered was of poor little OncoMouse, the first patented life form. After many months of running various images across the screen in my head, I saw her sitting in front of me. She had human arms and legs and little breasts. Her hand was tucked up under her mouse chin and she looked rather annoyed and resigned to her fate. I gave her a crown of thorns to acknowledge, as Haraway had, her passion, and placed her in a laboratory box, one where the eyes of the world were watching to see if she would save us, if she would be a rich commodity. I sent Haraway a slide and she wrote back: “ I am in love with ‘The Laboratory or The Passion of OncoMouse!’ It is playful and moving all at once, she is a perfect human/animal hybrid of technoscience, in the optic chamber of the lab and a superb FemaleMan!” I was thrilled by her response and gave her the painting. After receiving it, she wrote to me, ‘Your OncoMouse and the other potent images lets me tell people what figuration means in a critical theory of technoscience. Your painting has become part of my soul and part of my analysis, when I show your slides in my talks, people love them for themselves and also understand what I am trying to do better. Last week in Europe, I used the Laboratory in lectures I gave from my paper ‘Mice into Wormholes’. There is no question that audiences felt and thought differently because of the splicing of our work…We have built a dialogue in our work that neither of us imagined in advance. Our dialogic visual and verbal troping has become deeply synergistic.”

In 1994 Haraway sent me a draft of “Mice into Wormholes: A Techno-science Fugue in Two Parts.”9 It was an implosion of science and technology loaded with images. I loved the visual possibilities of what she referred to as “startling hybrids of the human and unhuman in technoscience. “ Shaping technoscience is a high stakes game, she wrote, “a form of life.” I was captivated by her description of the herbicide-resistant crops and genetically engineered plants. It was hard to resist combining a tomato and a flounder in a painting. But the image that lingered was of poor little OncoMouse, the first patented life form. After many months of running various images across the screen in my head, I saw her sitting in front of me. She had human arms and legs and little breasts. Her hand was tucked up under her mouse chin and she looked rather annoyed and resigned to her fate. I gave her a crown of thorns to acknowledge, as Haraway had, her passion, and placed her in a laboratory box, one where the eyes of the world were watching to see if she would save us, if she would be a rich commodity. I sent Haraway a slide and she wrote back: “ I am in love with ‘The Laboratory or The Passion of OncoMouse!’ It is playful and moving all at once, she is a perfect human/animal hybrid of technoscience, in the optic chamber of the lab and a superb FemaleMan!” I was thrilled by her response and gave her the painting. After receiving it, she wrote to me, ‘Your OncoMouse and the other potent images lets me tell people what figuration means in a critical theory of technoscience. Your painting has become part of my soul and part of my analysis, when I show your slides in my talks, people love them for themselves and also understand what I am trying to do better. Last week in Europe, I used the Laboratory in lectures I gave from my paper ‘Mice into Wormholes’. There is no question that audiences felt and thought differently because of the splicing of our work…We have built a dialogue in our work that neither of us imagined in advance. Our dialogic visual and verbal troping has become deeply synergistic.”

At this point we recognized that something extraordinary was going on. In that same letter she included an outline of her new book and requested that ten images be woven into the text. Besides “Venus” “The Laboratory” and “La Metiza Cosmica,” Haraway ultimately selected six more.

At this point we recognized that something extraordinary was going on. In that same letter she included an outline of her new book and requested that ten images be woven into the text. Besides “Venus” “The Laboratory” and “La Metiza Cosmica,” Haraway ultimately selected six more.

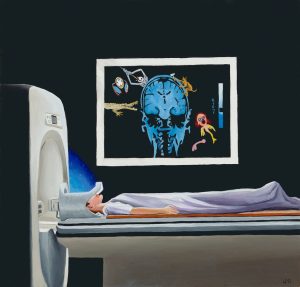

“Immeasurable Results” (1994) is an image of a woman entering a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine, one of the new medical imaging devices that promised so much. She is a response to our non-innocent resistance to the domination of technoscience in life and death decisions. The diagnostic film above the figure reveals more than a medical condition. A tiny red demon is pounding on her skull, repeating the loud noise the machine expels, a clock without hands but external crab claws hangs in anticipation, a calavera (skeleton) figure with a spear also awaits the crucial decision. An open-mouthed mermaid and a floating penis and testicles all attest to the immeasurable fears and desires in this woman’s head.

“Millennial Children” (1992) was painted in preparation for the Republican National Convention in Houston. Two young sisters (my granddaughters) kneel on the banks of Buffalo Bayou at night, surrounded by flames, like little Renaissance figures praying in purgatory. Behind them downtown Houston is burning and vultures perch in a tree awaiting their carrion. In the distance the towers of the South Texas nuclear power plant are smoking away, an oil field is blazing, and a stealth bomber is diving to the ground. The bayou on the right is polluted and the fish have bellied up. On the left, four large African wild dogs are stalking the girls. In the middle ground, a dancing demon with an image of George H. W. Bush in his belly rejoices in the havoc. It is a dystopian vision. Each child has a small guardian angel. The girls see the reality, but that may not be enough to save them from the apocalypse that engulfs the world in the new millennium.

“Millennial Children” (1992) was painted in preparation for the Republican National Convention in Houston. Two young sisters (my granddaughters) kneel on the banks of Buffalo Bayou at night, surrounded by flames, like little Renaissance figures praying in purgatory. Behind them downtown Houston is burning and vultures perch in a tree awaiting their carrion. In the distance the towers of the South Texas nuclear power plant are smoking away, an oil field is blazing, and a stealth bomber is diving to the ground. The bayou on the right is polluted and the fish have bellied up. On the left, four large African wild dogs are stalking the girls. In the middle ground, a dancing demon with an image of George H. W. Bush in his belly rejoices in the havoc. It is a dystopian vision. Each child has a small guardian angel. The girls see the reality, but that may not be enough to save them from the apocalypse that engulfs the world in the new millennium.

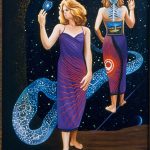

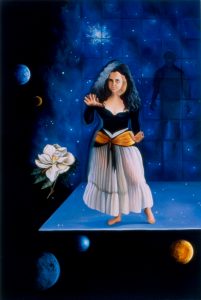

“Self-consortium” (1993) portrays a young woman (my niece) and her cloned android or trans-individual. They move inside and outside inner and outer space with a large serpentine strand of DNA. This young woman is like the Spider Woman, who spins her web out of her own body. The clone flaunts her electronic bio-constructedness. She grew out of Haraway’s work and many sci-fi novels. She crosses borders while doubling her power with new body codes. She will be able to negotiate a new world order.

“Self-consortium” (1993) portrays a young woman (my niece) and her cloned android or trans-individual. They move inside and outside inner and outer space with a large serpentine strand of DNA. This young woman is like the Spider Woman, who spins her web out of her own body. The clone flaunts her electronic bio-constructedness. She grew out of Haraway’s work and many sci-fi novels. She crosses borders while doubling her power with new body codes. She will be able to negotiate a new world order.

“Transfusions” (1995). Haraway sent me a copy of “Universal Donors in a Vampire Culture: It’s All In The Family, Biological Kinship Categories in the Twentieth- Century United States”10 in 1995. I was immediately taken with the possibility of painting a vampire, and not just any vampire. It had to be Max Schreck, the actor who played Count Orlaf in the original Nosferatu, F.W. Murnau’s 1928 silent film. I rented a copy and started drawing. The vampire sits in a teleoperating cubicle using his claw-like hands to manipulate the joysticks that control the activity of some dancing vampire bats as they penetrate the neck of a consensual woman laid out in black space. A medical stand with a blood bag and tubing is attached to her. The blood is moving from human to animal to machine to unhuman. It is a strange mating ritual in the night, a non-phallic fusion. It exemplifies the trafficking of vital substances across gender, race, species, and machines. Bloodlines are no longer pure. Racists beware!

“Diffraction” (1992). This painting alludes not to a specific text, but rather Haraway’s metaphoric use of a visual phenomenon that interferes with light. Diffraction does not reflect or displace light, but changes its direction. She uses diffraction as a metaphor for a place where change occurs and new meanings take place. In my painting an image of a powerful man stands behind the central figure of a young woman. He is a screened memory, one that marks a site of diffraction. The shifts that occur with age and psychic transformations, the multiple selves incorporated in one body are presented in the figure with its two heads, multiple fingers and the metaphysical space in between. Diffraction occurs at a place at the edge of the future, before the abyss of the unknown, the space occupied by the young woman in my painting. I’m trying to create bodies that matter. By imagining a woman’s realty in a sci-fi world, a place composed of interference patterns, we might become something different, something inappropriate, deluded, unfitting, and magical, something that might make a difference. I believe we need to be active about this, not removed, transcendental and clean, but finite, real (not natural) and soiled by the messiness of life.

“Diffraction” (1992). This painting alludes not to a specific text, but rather Haraway’s metaphoric use of a visual phenomenon that interferes with light. Diffraction does not reflect or displace light, but changes its direction. She uses diffraction as a metaphor for a place where change occurs and new meanings take place. In my painting an image of a powerful man stands behind the central figure of a young woman. He is a screened memory, one that marks a site of diffraction. The shifts that occur with age and psychic transformations, the multiple selves incorporated in one body are presented in the figure with its two heads, multiple fingers and the metaphysical space in between. Diffraction occurs at a place at the edge of the future, before the abyss of the unknown, the space occupied by the young woman in my painting. I’m trying to create bodies that matter. By imagining a woman’s realty in a sci-fi world, a place composed of interference patterns, we might become something different, something inappropriate, deluded, unfitting, and magical, something that might make a difference. I believe we need to be active about this, not removed, transcendental and clean, but finite, real (not natural) and soiled by the messiness of life.

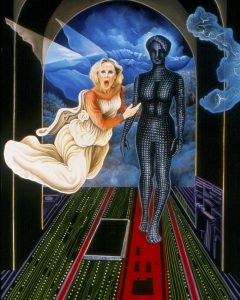

“The Annunciation of the Second Coming” (1996). This was the last painting I did for our collaboration. Except for her transparent wings, the angel on the left was roughly modeled after one of Botticelli’s paintings of the Annunciation. His angel calmly announces the coming of Christ and is very different from her postmodern sister, who is issuing a warning: life as we’ve known it is changing. The ethers of the past have escaped like the large strand of DNA that forms a galaxy on the right. The angel gestures toward the electronically constructed Galatea, a goddess who has left her pedestal and controlling creator. They are moving into the future through a sort of 15th–century colonnade with a computer circuit board for flooring. The wired goddess is shaped like a Greek statue, but the surface of her body is entirely digitalized. We see a collision of social fabrics from different eras and cultures. There is a danger here of becoming absorbed in the dreams and fantasies of a technological transcendence of the body and to demands for extenders of life beyond the possible and to becoming a technophilliac. Nevertheless, there are new technological devices that have enhanced lives, created freedoms and a sense of well being for many. And there is pleasure in becoming competent to manipulate them. Still, as Haraway writes in Modest Witness, “the classical and statuesque electronic goddess carries in her troubling body both a threat and a promise; she is a matrix, one who is pregnant with the contradictions, emergences, delusions and hopes of colliding sociotechnical worlds.”11

“The Annunciation of the Second Coming” (1996). This was the last painting I did for our collaboration. Except for her transparent wings, the angel on the left was roughly modeled after one of Botticelli’s paintings of the Annunciation. His angel calmly announces the coming of Christ and is very different from her postmodern sister, who is issuing a warning: life as we’ve known it is changing. The ethers of the past have escaped like the large strand of DNA that forms a galaxy on the right. The angel gestures toward the electronically constructed Galatea, a goddess who has left her pedestal and controlling creator. They are moving into the future through a sort of 15th–century colonnade with a computer circuit board for flooring. The wired goddess is shaped like a Greek statue, but the surface of her body is entirely digitalized. We see a collision of social fabrics from different eras and cultures. There is a danger here of becoming absorbed in the dreams and fantasies of a technological transcendence of the body and to demands for extenders of life beyond the possible and to becoming a technophilliac. Nevertheless, there are new technological devices that have enhanced lives, created freedoms and a sense of well being for many. And there is pleasure in becoming competent to manipulate them. Still, as Haraway writes in Modest Witness, “the classical and statuesque electronic goddess carries in her troubling body both a threat and a promise; she is a matrix, one who is pregnant with the contradictions, emergences, delusions and hopes of colliding sociotechnical worlds.”11

The collaboration between Donna Haraway and me culminated in the book, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©_ Meets_OncoMouse™. It is a dialogue between images and words that embodies ideas that we both were passionate about and reflects our dialogue with each other. Before the publication of Modest Witness in October 1996, Haraway sent me a letter in which she said “As you know, I feel like your paintings and my words are parts of a braided argument as well as a shared critical, hopeful, narrative and dreamscape about knowledge, politics and bodies of many kinds.”

There is an epilogue to our collaboration. In 1997 Haraway wrote a catalogue essay for a one-person exhibition I was having at Arizona State University Museum. She has a highly developed visual sense. Her ability to read visual language from cartoons, advertisements, charts, graphs, movies and paintings is acute. Haraway doesn’t just write using references to references or text upon text, she incorporates images and narratives from a broader world into her imaginative “Cyborg Surrealism.”12 Her talent for seeing and then translating the visual to the verbal would stand up with the best art critics and writers anywhere. She sees the variation and repetitions of forms and colors and how they shape an idea.

In the catalogue essay, “Living Images, Conversations with Lynn Randolph,” she begins a conversation with the paintings, but along the narrative path, the paintings began talking to each other and the viewers. Reading it astonished me.

In an interview with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, Haraway talked about our collaboration. Here are some of her responses. “ I feel about Octavia Butler much the same way that I feel about Lynn Randolph. Octavia Butler does in prose science fiction what Lynn does in painting and I do in academic prose. All three of us live in a similar kind of menagerie and are interested in processes of xenogenegis, i.e., of fusions and unnatural origins. And all three of us are dependent on narrative. Lynn is a highly narrative painter, Octavia Butler is a narrator, and, as you mentioned, the use of certain kinds of mythic and fictional narrative is one of my strategies.” And at another point in the interview, Haraway defends what Goodeve refers to as my use “of garish hyperealism to literalize the imagery and arguments.” Haraway replies, “I just don’t agree with your interpretation of Randolph’s realism. I think she is committed to certain ‘realist’ conventions and narrative pictorial content in order to foreground the joining of form and content. She takes up a resistance to the imperatives of abstract formalism as the only way to paint.” To which Goodeve replies, “which is what she means by ‘metaphoric realism?’ Haraway says, “Yes and for her, and me, this metaphoric realism–or cyborg surrealism–is the grammar we may be inside of but where we may, and can, both embody and exceed its representations and blast its syntax.”13

After Modest Witnesswas published and my Arizona exhibition was over, we relaxed into occasional e-mail updates. Although we haven’t continued our intense collaboration, her work remains an integral part of the way I see and think about the world.

Ours has been a dialogue between words and images that embodied ideas that we both were passionate about. These ideas bore witness to the dangers and pleasures of life on the earth at the end of the second millennium. Our words and images were not captions or illustrations of each other’s ideas. They were inspired by one another’s efforts and by the urgent social, cultural, and political practices we wanted to interrupt.

Ours was a feminist process. It was not a Socratic dialogue in any argumentative way, nor were we completing each other’s sentences. Rather we were two partners creating something new: a dialogue that recognizes parallels and differences. It was a relationship between word and image, one where word doesn’t dominate, where the two converge and both are ideas in there own realm. It was an embrace.

My collaboration with Donna Haraway began as a dance, not the close embrace of the tango, but one where two different figures entered the stage from opposite locations. Haraway, who moves through words, set the theme, and a slow pas de deux began. We were improvising, each expressing herself in her own way, but also in conversation with the other’s performance. Neither dancer led nor followed. There was no set choreography. The image-maker occasionally took flight, changing the lighting and movement, where upon the poetic partner embraced the colors and initiated her own riff. We seemed to amaze and delight each other as we moved harmoniously. When the ideas and spirit of one reached a finely honed image or text, the other drew inspiration and was spurred to greater heights. Thus we continued together and separately, searching and improvising until we found our groove, and together became modest witnesses to many worlds.

Notes

- Donna J. Haraway, “The Promises of Monsters,” in Cultural Studies by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula Treichler, Routledge, 1992, page 328.

- Donna J. Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©_ Meets_OncoMouse™, Routledge, NewYork and London, 1997, pp 125-126.

- William Simon, Postmodern Sexualities, Routledge, London and New York, 1996.

- Jessica Benjamin, The Bonds of Love, Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and the Problem of Domination, Pantheon Books, New York, 1988.

- Margaret R.Miles, Carnal Knowing Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West, Beacon Press, Boston, 1989.

- Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, translated by Gillian C. Gill, Cornell University Press, 1985.

- I’ve used portions of descriptions of several paintings from an unpublished paper, “The Ilusas (deluded women), Representations of Women Who Are Out of Bounds,” presented November 30, 1993 for The Society of Institute Fellows of the Bunting Institute. Donna Haraway quoted from the same paper in Modest Witness. The paintings so described are “Venus,” “Self-Consortium,” and “Diffraction.”

- Donna J. Haraway, “Living Images: Conversations with Lynn Randolph,” essay in Millennial Myths Paintings by Lynn Randolph, 1998, Arizona State University.

- Donna J. Haraway, “Mice into Wormholes: A Techno-Science Fugue in Two Parts,” Modest Witness, page 47.

- Donna J. Haraway, “Universal Donors in a Vampire Culture,” Modest Witness, page 213

- Modest Witness , cover description for paperback edition, 1997.

- Donna J. Haraway, How Like A Leaf, An Interview with Thyza Nichols Goodeve, Routledge, NewYork, London, 2000, page 120.

- How Like A Leaf, pp 120-122.