Selected Presentations

- The Soul’s Eye: Art in the life of people with terminal illness

The Fourth Annual Symposium "The Collective Soul", January 30 -31, 2015, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center - Unspoken Stories

Houston Seminar, February 2013 - Modest Witness: A Collaboration with Donna Haraway, 2009

- Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Techno-Angels: A Series of Spectacles

Center for the Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, 1996 and Arizona State University, February 1998 - Between Cultural Eras: The Effects of Postmodern Thinking on the Modernist Concept of Regionalism

College Art Association 83rd Annual Conference, San Antonio, Texas, January, 1995 - The Ilusas (deluded women): Representations of women who are out of bounds

Presentation for the Society of Institute Fellows at the Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 1993 - Secular Uses of Traditional Religious Images in a Postmodern Society

Women's Caucus for Art, February 1991

The Soul’s Eye: Art in the life of people with terminal illness

The Fourth Annual Symposium "The Collective Soul", January 30 -31, 2015, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

by Lynn Randolph

I want to thank Dr. Delgado Guay for inviting me to speak to you this morning and everyone else who helped organize this important conference.

I will be talking about my work with the non-profit organization, Collage, The Art for Cancer Network, which pays artists to work with patients at M.D. Anderson hospital and how that work exemplifies the healing power of art.

Because of privacy laws, I don’t have a lot of images to show you. I am usually reluctant to ask patients to sign a release during an emotionally intense experience. The art works belong to the patients and their families. With the patient’s approval, I sometimes take photographs of the images we create together.

For nearly seven years, I’ve been an artist-in-residence for Collage, a non-profit organization created by Dr. Jennifer Wheler, an oncologist at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. As an undergraduate, Dr. Wheler had studied art history. At our first meeting she impressed me by quoting the great American painter Georgia O’Keefe, who said,” I found I could say things with colors and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way… things that I had no words for.” Dr. Wheler understands that art is a universal language that transcends boundaries and can transform lives and that it can serve as a powerful tool in helping patients express themselves in the midst of emotional and existential turmoil.

My husband had been an M.D. Anderson patient. He died in July of 2000. Because I had gone through a significant loss, I was drawn to respond favorably to the offer to work in palliative care. As far as I know–and several people have researched it– I am the first or one of the first visual artists to work regularly in palliative care in a major cancer center.

Several of my friends who are psychotherapists tell me what I do is therapy, but I don’t get patients to draw or create something and then ask them to tell me about it or look for significant signs in their art work for us to explore. I’m not trying to help them change their lives or create new ones. It is too late for that. During the last several years I came to understand that I can help enhance the quality of this last phase in their lives. It took me a while to live through the questions with the patients to understand my task.

When I thought about my husband’s illness and death, I recalled that outside of close friends and family, I hadn’t wanted a lot of people around. Every day with Bill was precious. We were in sacred space.

Remembering some people then who tried to violate that space, I respect the patient’s and caregivers right to say no, I withdraw immediately. Some patients just want company and our conversation stays close to the surface. Others want to tell me about their lives and what they are going through and what’s important and meaningful to them. Still others find metaphoric language and images that are astounding. It is a privilege to be allowed into this space.

One of the nurses working on the unit when I arrived was a friend of a friend. She told me about patients before I knocked on their doors. She told me if they were alert and oriented, if they were alone or if a family member or friend or staff member was in the room. She would tell me if they were heavily sedated, delirious, or actively dying.

Some of the other nurses started helping me too, although several were skeptical and very protective of their patients, which I completely understood. One of them confronted me and said she couldn’t see what good I could do, that these were very sick people and I told her I agreed and had doubts myself, but I wanted to help and was going to keep trying for a while longer. Almost immediately after this encounter I got a phone call from Collage telling me that one of the physicians had asked that an artist see a middle-aged Pakistani woman over the weekend. On Sunday I went in, and the nurse who had confronted me was on duty and this was her patient.

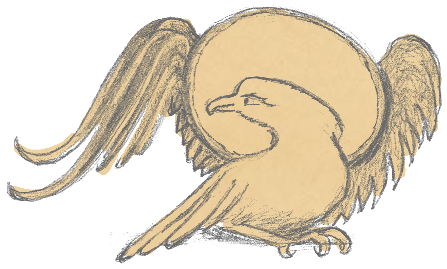

I asked the patient right away if she liked to draw or paint and she said she drew, but that she isn’t very good. She asked me to show her some of my paintings She was drawn to this image that I have on a card:

Suspended is a painting of a woman floating over a bed in an open room filled with water. The patient held onto the card for a long time and then she told me that it was like her religion. “Sometimes a soul gets stuck,” she said. “It can’t go to heaven or return to earth and powers have to intervene.”

I asked her what she liked to draw and she said “landscapes.” She said she had repeatedly tried to draw an image that she has in her head but she couldn’t make it look like she saw it in her mind.

I asked her if she would like to draw her image and she did, it was like a typical eight year old might have drawn and she was very frustrated with it. She had described it as “a house with large trees around it and an abundant garden.” When I saw her drawing I understood that it was a cottage in the woods with an abundance of brightly colored wild flowers. She asked me to draw it. Using colored pencils I drew a forest thick with trees and two large trees near the house. She was sitting behind me on the bed and when I started putting in the wild flowers I heard her whisper “Oh God.” I just kept on coloring and then she said, “ It’s just like I see it.” I felt like someone else had been drawing or that the drawing drew itself. When I finished she thanked me profusely and asked to buy it. I assured her that the drawing was hers and she said she would have it forever and then she burst into tears.

I stayed a few more minutes, but I could tell that she wanted to be alone and so I asked her if it would be ok if I left and she seemed relieved. I had been with her for over two hours but I wanted to tell the nurse what had happened. She was amazed. We were standing outside the rooms talking when the patient emerged with her IV’s and began walking around the unit. She was smiling and her skin looked radiant, much changed from earlier in the day.

I’ll never know what that particular image meant to her, just that it was very important and she was no longer stuck. The nurse, who I think of as a friend, is now very supportive and appreciative of my work. I rely on the nurses who care deeply about the patients to help guide me in my initial encounters. The doctors, social workers, chaplain, counselors, and therapists all have helped and have made me a part of the palliative team.

The White Dress:

One afternoon, a favorite nurse asked me to look in on a patient from Jamaica who had esophageal cancer. The patient’s two sisters and her daughter were with her. All of the women loved art and were eager to tell me about their favorite paintings in Caribbean museums. I showed them some of my paintings of the Texas coast, including this one:

We talked about the beauty of living near a big body of water. The patient who seemed to be in her late 50s, and was very beautiful, said, “I have a vision.” We all leaned toward her.

“I’m walking on the beach,” she said, “and I’m wearing a long white dress, with long sleeves (and she gestured with her hand down her arm) and no underwear. I’m listening to music on my iPod.”

One of the sisters said, “And are your little feet getting wet?”

“Yes,” she said, and she described the feeling of the water on her feet as she went splashing along.

The other sister said, “And is the wind blowing through your hair?”

“Yes,” she said, and we could all feel the cool air in our hair. We were all walking with her drenched in the pink light of the setting sun, all of our senses immersed in this moment. Everyone in the room had helped create another space, one very remote from the one we were standing in.

Our walk was interrupted by the patient’s oldest and dearest friend, who had just arrived. Before I departed I hurriedly gave them one of the sketchbook/ journals that I carry with me and suggested that they all write or draw in it. The following week the nurse told me that this patient was in a coma and actively dying. As I walked down the hall I saw one of the sisters and the daughter. They came running up to me and the sister said “You did a wonderful thing for us.” They had spent a good part of the weekend filling up the sketchbook and the patient’s only granddaughter had told them “When Granny dies I want that book forever.” The sister looked at me and said, “And we are going to bury her in that white dress.”

Defining Home:

Sometimes patients have just come to the unit after being told that there are no more treatments available to them. They can be unnerved and disoriented. Ms. J. was a middle-aged woman who lived alone in the country. She was anxious and in pain. She seemed to need someone to listen. She said that she had been feeling bad and came into Houston for help. Two weeks earlier she’d gone to another hospital where she said a nurse told her that she had cancer and needed to face up to it.

I got her to start describing her place in the country. She drew a rough sketch of the layout of the property and then I started drawing the details as she indicated. We drew the house, and the porch, and we put every tree in place and then fenced in the chickens and a cow. She had ten dogs and a cat. She became engaged, telling me where to put everything: the dog houses, the chicken coop, even the food bowls. Ms. J. had relaxed. Her pain and delirium had diminished. We were at her place.

We all have a screen in our mind, one that we project images across. We know this from our ability to dream and hold memories that we can retrieve. Sometimes the images reveal our fears and desires. They come from deep within the psyche and they have transformative powers that can make our lives whole.

A large part of my job as artist-in-residence on the palliative care unit is to be a translator, a conduit, a means whereby patients can express the images they hold in their minds that embody their memories, dreams, and reflections and convert these images, that have meaning for them into drawings, paintings or other art forms.

When patients find an image that is internal or buried in the unconscious and with my help can make it external, visible and conscious, they feel a powerful connection to it. Often they recognize something that relates to the goodness within them. The artwork helps them feel whole or complete or restored. Usually when that happens, their eyes fill with tears or they suddenly become radiant, or both. In these moments I feel whole and complete and elated too. That’s also how I feel when I complete a painting that is meaningful to me.

Some time ago I worked with an extraordinary young man who had recently finished medical school. I will call him James. He was thirty years old. The week after he received his match at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in anesthesiology, he was diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer. He had been through twelve rounds of chemotherapy and radiation and was now in palliative care. James and his mother welcomed me into their room. He wanted to talk to me about painting and he was quite knowledgeable. I asked him if he liked to draw or paint and he just laughed and said no. I asked him if he liked to write. He said he had written an article for a medical journal. He was proud of this work and said writing it had helped him. He seemed accepting of his life’s tragic turn. He knew that he was unlikely to ever practice medicine. He told me that part of his regret was that he would be able to empathize with patients far better than before his illness, and that he was shocked at how difficult it all was to process.

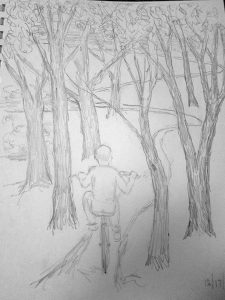

When I asked him if there was an image in his mind that had meaning for him, he seemed puzzled. Nothing came to him at first, but he took his time and finally said that he could see himself when he was twelve years old getting on a bicycle and riding on a path through the woods near a high lake in the hills of Tennessee. This was where his mother grew up and they had visited many times. He paused again and then told me that this was his first memory of being consciously happy.

I asked him if he would like me to draw that and he said yes. I drew the back of a boy riding his bike through the trees on a winding path.

While I was drawing I looked up and he was crying, remembering how happy he was and wondering out loud if he could ever feel that way again. His mother tried to console him, but it was a painful moment. When I finished the drawing his mother saw it first and said, “That is how it was.“ James nodded and just held the sketchbook and stared at it. He was beaming.

When I got home I checked out his article on the Internet. It is full of self-awareness, courage, and insight. I hoped having recovered that acute feeling of happiness, he could return in some way to that path again for the rest of his journey.

Months later James and his mother returned to the hospital. I saw his name on the list and went in to see how they were doing. James was unconscious, the room was dark and I slowly and quietly moved towards his mother and asked her if she remembered our visit. She smiled and said, that as time had gone by, James told her to get rid of most of his personal effects, but to hold onto that drawing. She assured me she would.

There is no way to generalize about the mystery that is behind each door and there is no preparation except to be completely open to what each unique encounter brings. I rely heavily on my intuition to guide me. It is the patient’s desire to bring forth the psychological and spiritual dimensions of their own lives that determine what we do. I turn myself over to whatever happens. The first moments are fragile and tender as I wait for a response to my introduction. I feel I have to enter each room in a state of almost complete passivity and openness to the experience that awaits me. It’s a bit like sailing, I have to feel the emotions stirrings to know which way to tack or turn. Sometimes just remaining still can smooth the way to revelation.

Nothing prepared me for a woman I will call Gabriel. The vision of Gabriel sitting up in bed, her long arms extended along each guard-rail and her head turning slowly to greet me is burned into my retinas. She looked like a barely living skeleton, her dark skin stretched tightly against her almost visible bones. Her protruding teeth and the corneas of her eyes were so white they appeared much larger than they were. I found it difficult to believe that she was alive. She had a thick bubble of black hair–a wig–and matching false eyelashes. She had painted the nails of her very long fingers with raspberry-colored polish.

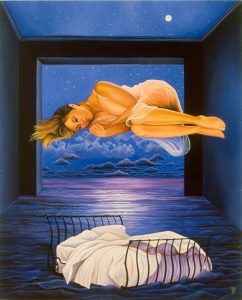

Gabriel’s mother beckoned me in. I introduced myself and told her that I was a painter. Her mother said that Gabriel was an artist, too, and that her home was filled with her artwork. The mother asked to see some of my paintings. I pulled the post cards from a folder and started showing them to Gabriel and her mother. A few of the images had figures in them.

Gabriel was particularly taken with this one. She could not let it go. She stroked the card and stared at it for a long time. I felt as though she had gone into the seascape, or light, or beauty. She had left us. Gabriel could barely speak. She made guttural sounds that only her mother seemed to understand. As I was about to leave and had coaxed the postcards back, Gabriel made a sound that I misinterpreted as one of physical pain. I left to allow her mother to attend to her. I was standing outside her room when Gabriel’s mother came out to ask if she could buy one of my paintings or a postcard. I told her I would be happy to give her one and went back in the room to let Gabriel choose one. She sorted through the cards, holding each one gently and touching different parts of each image. I realized that she had to have them all and gave them to her. The sound of pain was at the loss of those post cards. I did not expect her to live through the night, but she had something to hold onto.

The next week I found Gabriel alone, sitting up in bed She looked stronger and wanted to talk about art. She asked for a pencil and paper. I could hardly believe that she felt good enough to draw, but she drew several really nice butterflies. I told her how the children in one of the Nazi death camps found old nails and sticks and etched images of butterflies on the walls. Gabriel understood metamorphosis. She said that she was planning to go home. She lived with her mother and a son. She said her mother was scared and uncertain of how to care for her. Gabriel said that some people get so beaten down when they are kids that they never feel capable. She told her mother, “You have to be gentle with everything you touch,” and “Just give me a kiss, just stay connected.” Gabriel gave me the butterflies. As I was leaving, her mother appeared and I showed them to her and she seemed to love them, so I gave them to her thinking how much they might mean to her later.

The following week Gabriel was still in her room. It is unusual for me to see a patient more than two weeks in a row. Gabriel was sitting up, full of grace and style, wearing a leopard-print turban and talking to an attractive young man. He said that they had performed together for several years, and that Gabriel was a great vocalist. I asked him to tell me about their performances. He told me several stories and Gabriel seemed to enjoy listening and reliving their time together. He said that she had BIG hair, always wore black with something in a leopard pattern. I told him that she was a very talented artist and that she had drawn some lovely butterflies the week before. She asked me where they were and I told her that I had given them to her mother. She became agitated. She had wanted me to keep them. It had been a trade: my post cards for her butterflies and I had violated the trade. She found a large scrap of paper, asked for a pencil and drew another butterfly. Then she drew a line coming down like a kite tail from the butterfly and drew herself with big hair and thick eyelashes wearing a black dress holding onto that kite’s tail and flying off with the butterfly. She motioned for me to come closer and put her right hand up with the palm facing me. Then she pointed to the veins she had drawn in the butterfly’s wing and showed me how she had repeated the lifelines in her hand on the butterfly’s wing. I told her I would always keep and treasure that drawing. It is the only patient drawing I have. Remembering her advice to her mother, I kissed her on the cheek when I left. She died at home a few days later.

With the exception of Gabriel’s drawing, whatever images come out of these experiences belong to the patients or caregivers. I often have to do the drawings quickly, sometimes in the dark and sometimes with a mask and gloves on. Sometimes I feel the drawings draw themselves and that I’m barely there. The work is rarely a finished work of art, but it has powerful meaning for the creators. They have strengthened my belief in the representational and metaphoric ways one can communicate the soul.

Not all the patients and caregivers that I work with discover images that are deeply meaningful. Some of their images are predictable and stereotyped, like colorful flowers, dogs or cats. Drawing or painting can be a relaxing and pleasurable activity regardless of the content. The act of creating images with patients, whether I do it or they do it or we both do it, distracts some of them from their pain, anxiety, or depression, and helps bring them back to their own lives and ego integrity and away form the medical world they are dwelling in.

One day one of the male nurses told me that there was a young man on the unit who is an artist. The nurse said that he had only been drawing for several months, but he had a lot of drawings. When I walked in and saw him, he looked familiar. I had helped him start drawing months before. He had filled the sketchbook I had given him and most of a much larger one he had acquired. He was very excited to see me and show me all of these mostly cartoon-like drawings. He had discovered a talent he didn’t know he had and drawing was now a part of his daily routine. His art enhanced the quality of his life.

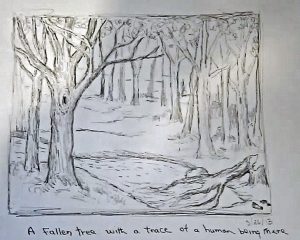

One afternoon last year I met a thirty-one year old man, I will call Bryan, who worked in information technology. He had lived in the Northwest before he had left home, gone to school and later worked in Colorado. He was sitting in the middle of the bed with crossed legs and his mother was with him. He said he liked to dabble in watercolors. I asked him if he would like to paint and he declined but said he might do some drawing. I could tell he felt a little intimidated and didn’t want me to see him draw. He also liked to write and he read a lot of science fiction. As we were discussing sci-fi, he told me that he had visualized his cancer as a dragon. I told him he could draw that but he felt self-conscious and asked me to do it. I told him we could do it together. In his vision he saw his chest open, revealing his heart, which the dragon was trying to devour. He said the chemo was supposed to have cut off the blood to the dragon, but hadn’t.

I drew him with an exposed chest cavity and Bryan drew the heart. He wanted me to draw the dragon, which I did. It had a wide mouth that surrounded the heart and claws digging into his shoulder and a tail wrapped around his neck. Bryan was amazed. He drew arrows sticking out of the dragon and other wounds on its body. Then he colored the wounds and the heart red. He seemed to enjoy working with me, but I could tell he wasn’t satisfied. He had already accepted the fact that the dragon couldn’t be defeated, and he wanted another image.

He told me how much he loves the rainforest on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State. I have been in that rainforest, where saplings sprout from the trunks of fallen trees and continuously bring new life. The rainforest is close to where he had chosen to spend his final days in hospice. He wanted me to draw a stream running through the woods. When I finished drawing that and showed it to him, he said he wanted something else that would catch attention, a fallen tree. So I erased an area and drew a tree that had fallen partially into the stream in the foreground.

Bryan looked at it and asked me if there was something else I could draw that would indicate that someone had been there. I drew a pair of footprints entering the drawing on the lower right bank of the stream. He held the drawing close to his body and told me he loved it.

My final story this morning is one in which my participation was minimal. One afternoon while going over the list of her patients to tell me who she thought might be available, one of my favorite nurses described a woman in her mid 50s as being sad, frustrated and depressed. She said that the patient lived alone but had an adult son who couldn’t seem to help her handle things such as her insurance problems and other arrangements. She had been trying to negotiate between him and the insurance company all morning. So, I expected to see a reluctant frustrated woman. Instead the patient told me very pleasantly that someone had told her I might come by. She was alert and enthusiastic, although I could tell she was in some pain. I almost never encounter patients who just want to dive in and create something on their own, but this patient could hardly wait. She said she liked to work with all kinds of media: oil paint, acrylics, colored markers, pencils, and water- colors. I opened my bag of supplies and she chose water colors and colored pencils.

She started by painting one long purple sweep of a line followed by a turquoise blue one beside it. She told me later that she was trying to think of sacred colors and these were her choice. She wanted me to talk to her while she was painting. I was seated so that I couldn’t see exactly what she was painting. So I chatted with her while she painted. Her son called and she calmly told him to call back in a little while that she was painting. One of her good friends arrived and she asked her to sit and wait that they would visit after she finished painting. She seemed happy and excited to have this opportunity. After a while she said, “this is so relaxing.” I asked her how long it had been since she painted and she said, twenty years. The paint was flowing and she seemed very confident about what she was doing. I was thrilled to find a patient alert and capable of painting. I thought she was enjoying the paint and making an abstract design. She didn’t seem concerned with a subject or representing anything. She was talking about her life, how she had taught kindergarten for many years, then decided to become a golf caddie, and then went to work at a health food store. Her friend had a better view of the painting than I did and kept telling her it was beautiful. Finally she finished and I glanced at it not really seeing it and I looked again and saw the hands.

I looked at her and the painting and she said, “Take me Lord” and then, “I’m ready.” I could now see her reclining body, it was smooth, non-resistant. She seemed as if she could just slide away. She lifted the palm of her hand in a submissive gesture. She pointed to the areas of dark red. That was the pain shooting down. She had used the colored pencils too encode her initials in the pattern on the lower left of the painting. She said she wanted to title it “Peace”. “I’m at peace,” she said. She had taken what was within her soul and had directly made it visible. It was a sacrament, an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace. I looked at her and told her that this is what art is, the real thing. She was glowing.

I realized after I left the room that this was an artwork we could share and I went back in the room and got her to sign a release, allowing me to reproduce it for others to see. She was very pleased to sign her name.

Thank you very much.