Selected Presentations

- The Soul’s Eye: Art in the life of people with terminal illness

The Fourth Annual Symposium "The Collective Soul", January 30 -31, 2015, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center - Unspoken Stories

Houston Seminar, February 2013 - Modest Witness: A Collaboration with Donna Haraway, 2009

- Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Techno-Angels: A Series of Spectacles

Center for the Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, 1996 and Arizona State University, February 1998 - Between Cultural Eras: The Effects of Postmodern Thinking on the Modernist Concept of Regionalism

College Art Association 83rd Annual Conference, San Antonio, Texas, January, 1995 - The Ilusas (deluded women): Representations of women who are out of bounds

Presentation for the Society of Institute Fellows at the Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 1993 - Secular Uses of Traditional Religious Images in a Postmodern Society

Women's Caucus for Art, February 1991

Unspoken Stories

Houston Seminar, February 2013

by Lynn Randolph

Part I

Thank you for inviting me to speak to you this evening. I feel honored to be a part of this series.

In the spirit of your previous presenters, I would like to begin by telling you some stories, stories about images.

I will be talking about my work with the nonprofit organization, Collage, The Art for Cancer Network, which pays artists to work with patients at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Every Tuesday afternoon in my work as artist-in-residence on the palliative care unit at M.D, Anderson hospital, I see dying people.

A few weeks ago I knocked on a door and heard a man say, “Come in.” He was sitting in the dark holding his mother’s hand and crying. She was a heavy woman in her late 60s and was not conscious. Her tall, slim, mustached husband stood by the side of the bed, his red-rimmed eyes full of sadness. I told them who I was and why I’d interrupted them and I waited to be dismissed, but they invited me to stay. “What can I do?” I thought. “They have formed a sacred circle of love around her and now does not seem like a good time to interfere.” Intuitively I blurted out, “Is there anything I can draw for you?”

“Can you draw some mourning doves?” the husband asked. “Yes,” I said, and sat down and pulled out of my bag of supplies one of the handmade paper sketchbooks I designed just for this purpose. I proceeded to draw two mourning doves suspended in flight and handed it to the husband. “Oh,” he said, and clasped it to his body. He shared the drawing with his son and they both thanked me. I left them with his metaphor of the Holy Ghost, the image he wanted to be with them in their circle.

The sacred is defined as being set apart and as needing protection. I think of the first moments when I enter each room as being fragile and tender. Each situation is unique and I never know what is awaiting me on the other side of the door. I absolutely respect the patient’s and caregivers’ right to say No. Some patients want to tell me what they are going through. Others just want company. Still others offer astounding metaphoric language and images that connect to something deep within.

Not infrequently one of the doctors or nurses will have a patient or caregiver they want me to see. Early into my now almost five years of doing this work, I was greeted by one of my favorite nurses. She told me that a young woman in her twenties wanted to work with me. She cautioned that the woman was having some treatment that is usually exhausting. When I entered her room, she pulled herself up and greeted me. I was struck by her lovely face, bald head and gentle eyes. She had never painted before she said, but she wanted to try. I told her I would help her and asked what she wanted to paint. “A waterfall,” she said, and started describing how light falls and goes through the moving water.

I got out my watercolor set and filled a hospital cup with water. I drew the composition as she described it: a high rock ridge with water overflowing it down into an ovular pool at the bottom, surrounded by large boulders. I told her I would paint one side of the picture and she would do the other. I painted a few inches down and handed her the brush, she painted down to where I had stopped and handed me the brush. We continued this process slowly and in silence.

About half way down she said, “This is so relaxing.” a phrase I’ve heard many times since then. I noticed that she had a lot of control of the brush and was doing quite well. At one point she said “I love to watch your hand painting,” and I realized that no one watches me paint in my studio and told her so. When we finished she was happy with the result and recognized that this was something that she was good at, a talent she had never claimed. I looked at her and she didn’t seem at all tired, but radiant. She had been able to take something that was inside her, an image of light and water and make that visible. She had forgotten her discomfort and the exhausting treatment she’d experienced that morning. I left feeling good, but not without thinking of her short light life falling into the eternal blue.

One day Dr. Paul Walker, who is head of the palliative unit, recommended I see an attractive, late middle-aged man. He was dressed and standing in the middle of the room when I entered. He was welcoming and beckoned me to join him. He seemed very accepting of his situation, but extremely concerned for his pre-teenaged daughter. I told him that I was an artist and he seemed puzzled and curious. He couldn’t figure out what to do or what I wanted, but he was very open. I just kept talking and asking him questions.

“This is very surreal to me,” he said, “like something wonderful is happening.” I asked him to tell me about himself and he looked at me directly and said, “I am a fisherman.” I showed him my little paintings of the Texas coast that are on postcards. He looked carefully at each one. He told me that a lot of people don’t see the coast like that. “They can’t see the beauty,” he said. It turned out that his favorite place to fish is a bay where my husband and I have a small cottage. I pulled out my watercolors and began to paint. “What time of day do you like to go?’ I asked. “Early morning when the sun comes up,” he said. “Do you go out in a boat or wade?” I asked. “I wade out to a sandbar,” he said. “And what color shirt do you want to wear?” “Blue,” he replied, “something between the water and the sky.” As I was painting a glorious sunrise with this fisherman in his blue shirt standing on a sandbar at dawn, he told me he had been writing his daughter letters, one for every birthday, her high-school graduation, college graduation, marriage and first child. I painted the sun rising midway over the horizon line with two radial arms of light parallel to the horizon and a vertical reflection on the water. I became aware that I had painted a cross and was afraid it might offend him. Moments later he announced that he had become a Christian only a few weeks ago. I was relieved and continued, directing his fishing line into the golden cross. When I gave him the painting – a gift for his daughter — he was overcome and found it difficult to express his gratitude. He wanted his daughter to see the beauty of that landscape and a man who loves to fish.

Another one of Dr. Walker’s recommendations was a Russian woman in her thirties. He said she was alert, very bright and extremely autonomous. Her mother and brother were in the room, but spoke little English. I will call her Ana. Ana was making her own arrangements to go to a hospice. She generously greeted me and inquired about my mission.

After I told her a little about my visits and asked her if there was an image in her mind that she wanted to express, her head moved slightly in a way that revealed a significant idea or image had occurred to her. She said that she would like to try, but that her mother and brother would have to leave the room. As they were leaving they reminded her that an orthodox priest was on his way to see her. She seemed unflappable and sent them off.

Ana had lost all her hair and a large tumor was visible on the right front of her head, which partially closed her right eye. She was invigorated and eager to begin. Immediately after her family left the room, she blurted out that she had an image of her tumor. It was a large, rounded, solid form that was ugly and had bruises around the edges. It was a flesh color with awful browns and purples and bloody parts. She said her white blood cells were white knights and they were attacking the tumor. She was very intense and talking so fast I knew it was going to be hard to capture everything in one image. I felt like I should be making a film. It needed a storyboard.

The few white knights became a whole army. They couldn’t use guns or explosives because that would damage the healthy parts. So, she armed them with axes and swords and knives. Their work was very bloody. An angry face appeared on the tumor. Its grimacing mouth kept consuming her good cells, so it had to be mutilated. Ana had closed her eyes and thrown her head back as she released her vision.

“The white knights are armored and they are highly organized, they are parts of myself,” she said, “and very protective. They are stronger than the tumor and they go straight to the mouth, to block it, to kill it. There are little noises. The mound of tumor begins to look like it’s suffering, it’s being cut up into layers and pieces, it’s limbs have been cut, it is dissolving.”

She said she felt victorious. The white knights continued to work and Ana said, “I’m standing watching all of this. I’m in command of the army of white blood cells and all its divisions.” She said the inside of her body was blue, sky blue. Then she saw a flag, a blue flag with an image on it, an image of a girl running. “The girl is me a healthy human running,” she said, and she interrupted herself to say, “I can’t run anymore. It hurts to move.”

But she continued. Every time she saw the flag she felt stronger. The running girl on the flag was throwing a spear, which became many spears. The tumor was diminishing and becoming paler. Next she saw herself with a saw and axe. She destroyed the tumor and lymph cells came with pitchforks and wheelbarrows and carried off the pieces. The army of knights was celebrating. They were flying her flag.

“Everyone is joyous,” she said. She heard a battle cry and they were all yelling Ana, Ana, Ana.” Finally she said she saw a “newly prepared ground” where her tumor used to be. “The spot is ready, pure, clear,” she said. “And I’m staking my ground and planting my flag in the newly prepared territory. On the flag you can see the person running. It’s me, and I am victorious.”

I had drawn the white knights attacking the tumor with nasty colors and grimacing mouth and lots of blood. One charging knight held a flag with an image of Ana running and throwing a spear. I showed her the drawing and she held it close to her body. She began to cry. She said she was crying “because it was me.” After drying her eyes she thanked me. Her face was clear and flushed and radiant.

Ana’s brother entered to tell her the priest had arrived for her last rites. On my way out I passed him in his full regalia. I was overwhelmed by the depth of this lovely young woman’s sacred vision. I knew she couldn’t survive physically and that she was running as fast as she could to rid herself of the misery embedded in her body. She was going to the “newly prepared ground” that was “clear and pure” where she would plant her flag forever.

There are many stories I could tell you of how creating images with these patients whether I do it or they do it, or we both do it, has the power to distract them from their pain or anxiety and helps bring them back to their own lives and ego integrity and away from the medical world they are dwelling in.

My favorite sessions are with patients who retrieve an image from deep inside themselves and make that visible through our work together.

Once I visited a middle-aged couple. The wife was ill. They had five children; the youngest was seventeen years old. They greeted me with open warmth and easily began to talk about their lives. They had met when they were both in college. She described her cancer and learning recently of her impending death. She looked at me and said, “This sucks.” I looked back at her and said, “Yes, it sucks.”

Then I asked her if there was an image in her mind that had special meaning to her. She became still, put her head down into her hands and after several minutes of silence she began to sob. Finally she looked at her husband and said, “It’s that chapel.” He knew right away what she meant. She was sitting in a chair out of bed and I pulled my chair up close to hers and asked her to tell me about that place. I started drawing what she was describing.

The chapel was a small, open-air, rustic structure behind a large Episcopal church. She found it one day on her way home from school when she was twelve years old. She started going there almost every afternoon after school to delay going home to what she called her dysfunctional family. She described the chapel as being open, with a large rectangular window over a simple altar. The light streamed through the window in the afternoon. When she faced the light, she could see trees and birds. I asked her if she sat or knelt. “Knelt,” she said. I asked her what color her hair was when she was a girl and she said, “I was a towhead.” I drew this little girl kneeling with her white-blonde hair and head facing the light and life she would claim.

As I was drawing and coloring I heard her whisper, “I feel like I’m there.” She said that this sanctuary and the god within had saved her life. She told me that her siblings had never found this kind of solace and had led difficult lives. She believed that finding the chapel had enabled her to go to college and find her husband and build a close family. I gave her the drawing and she held it to her body and with tears and a smile thanked me. As I was leaving the room I glanced back and saw them embracing and crying together.

When patients find something that is internal or buried in the unconscious and can make that external, visible and conscious, they feel a powerful connection to that external object. Their visual metaphors help them recognize something in their lives that often relates to the goodness within themselves. The connection is something they can bond with and it makes them feel whole or complete. Usually when this happens their eyes fill with tears or they suddenly become radiant, or both. In these moments I feel whole and complete and elated too.

There is no way to generalize about the mystery that is behind each door and there is no preparation except to be completely open to what each unique encounter brings. I am a translator, a conduit. It is theirs to bring forth.

Often before I go to the hospital, I think to myself, what wonderful people will I meet today and what will I learn? One day when I arrived I found one of my favorite nurses waiting for me. She said there was a woman on the unit who really wanted to work with me. She was in her late sixties and her husband was close to death.

When I entered he was lying unconscious with an oxygen mask covering his face. I sat down next to her and told her that my husband had been a patient at M.D. Anderson and died several years ago. This allowed her to tell me what she was going through and we shared some of our pain and grief. She liked to draw and make things with her hands and she intended to take art lessons after he died. She said that she could only draw inanimate things. I gave her a sketchbook and pencil and we talked about making something related to her husband.

She decided that she wanted to draw his hand. It was swollen and drawn up into a claw. She carefully straightened each finger and placed his hand by his side. She sat down, picked up the pencil and sketchbook and asked how to begin. I told her to look at the outline of his hand and let her hand follow her eye and begin drawing. She drew a very nice hand that captured the character of that old paw. She was weeping while she was drawing and I could feel her remembering that hand holding her, helping her, embracing her. With tears in my own eyes, I helped her finish shading it. She told me that she thought about taking photographs of him, but that this drawing would always mean more to her.

Whatever art comes out of these beautiful experiences belongs to the patients. These are their images, even the ones that I do, and I don’t keep them. I often have to do them quickly, sometimes in the dark, sometimes with a mask and gloves on, and sometimes copying blurred photos from a cell phone. Sometimes I feel the drawings draw themselves, that I’m barely there. The work is rarely like a finished work of art, but it has real meaning for its creators. I have come to see the power of representational images in peoples lives in a profound way.

Part II

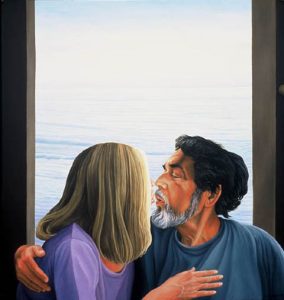

My husband, Bill Simon’s death in the summer of 2000 helped prepare me for my work at M.D. Anderson. It took more than five months after Bill died before I could pick up a paintbrush. Then for almost two years I painted and cried. These paintings, the death paintings, helped me live through my deep loss.

Click images to view in lightbox.

My step-son took a photograph of us sitting in the kitchen on the Monday before his death on Friday. I changed the background and enhanced the light and colors. We are only a breath away.

During the months when I still couldn’t pick up a brush, I found myself looking at Renaissance paintings of Lamentations, Descents from the Cross and Pietas and seeing them with new eyes. The grief, so deeply expressed in many of the paintings, was very moving to me in a more personal way. While I was painting this Lamentation, I felt like I was touching him with my brush, I could feel each distinct feature, his finely chiseled nose, and his thick black hair and while it was excruciatingly painful, it was done with great love. Love is an achievement that life does not erode or death diminish.

Bill took on his own death with incredible strength and grace. He was highly aware of his total environment for most of his life. The painting of the Mage includes the refineries at night, downtown Houston, the freeways, and a large Galveston wave rising up in the bed. Cancer cells circle his body. The metallic light in the tunnel of medical imaging devices predicts an awaiting world beyond. Bill stood up for what he believed and for many less fortunate than himself. There is a way to think of portraits of the dead as extensions of life. One is able to detect in them an increase, a regaining of force, a sort of potency beyond replacement or substitution. For me, this painting is an image of resurrection. I could see him alive again and I no longer felt the need to keep painting him. After finishing it I was in a quandary. I have been a figure painter for most of my life, but there was no one else I wanted to paint.

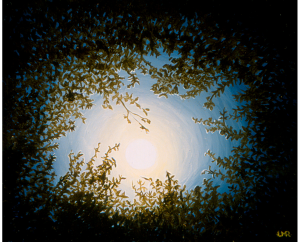

I turned toward nature, toward the landscape void of incarnate souls. Bill didn’t share my love of the natural world. He wouldn’t go anywhere where there wasn’t a Holiday Inn within fifty miles. I had taught him to see the moon through the trees. So I painted maybe six or seven of these. In several I stopped painting the trees as I was moving from the center out and realized I had painted a wreath around the moon. It occurred to me that looking at the moon through the trees might have been the origin of burial wreaths in ancient Greece.

Bill liked to go to Galveston and we spent many hours holding hands and walking on the beach. I took a photograph of this wave late in the afternoon on New Years’ eve, 1999 with Bill standing beside me. I came upon it after he died and painted two versions. Recently I was reading a poem by Zbigniew Herbert ( Zbignef Xerbert ) and these lines came off the page: “ those who sailed at dawn but will never return left their trace on a wave.”

An elegy keeps our losses from oblivion; it struggles to immortalize them and recognizes the miracle of someone’s life. For the next four years I went up and down the Texas coast and painted elegies trying to make the invisible visible, the absent present.

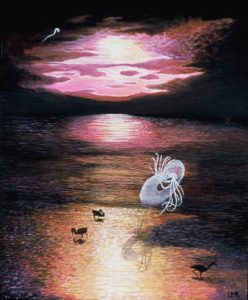

6. (“Moonrise, Shorebirds, Spirit”)

6. (“Moonrise, Shorebirds, Spirit”)

In several of them I created small transparent forms that lingered over the water and marshes. They are spirits-presences that comforted me.

The meaning of a painting extends beyond the visible and emotions like grief, desire, pain, joy, fear, ecstasy are not easy to make visible. The challenge is to create visible equivalents to the feelings. I wanted sunsets and sunrises the sacred, quiet in-between times. I wanted the nightscapes, the glowing moons and auras around clouds, that represent dreams of immortality, and I was going to have to wander all alone through the night to capture them.

8. (“Sacred Wedding In The Night”)

8. (“Sacred Wedding In The Night”)

came from a deep understanding that part of me went dancing off with him. That the way I was with him was a way I would never be with anyone else.

comes from a similar recognition that my love like a winged garment was wrapped around him and went with him.

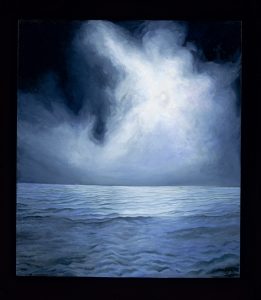

10. (“Moon through the Clouds over the Gulf”)

10. (“Moon through the Clouds over the Gulf”)

this is one of the paintings that is reproduced on small postcards that I show to patients. Doing these paintings brought me a lot of peace and serenity. Finally, after painting about ninety-six of these elegies, I could see a figure floating.

She is floating over the water, merging with the clouds and the paintings that preceded it.

In this painting I moved to a more liminal state. It is dawn, between night and day, dark and light, between water and earth and sky. It is between impending death as represented by the flying vulture and life as seen in the gentle presence of two white pelicans. And the woman is neither alert, nor asleep, but caught in a liminal and vulnerable state.

The young woman, in this painting, is fully alert and capable of defending a family of whooping cranes in the Texas Marsh. Of course, she is endangered too. At this point in my recovery, I had fallen in love with a wonderful man, Michael Berryhill, and he had a ten-year old daughter, and we formed a new family. Michael loves the Texas Coast and has written about it extensively. He had, and we continue to have, a cottage on San Antonia Bay, which we visit frequently. Michael is also a bird-watcher.

During all my journeys up and down the coast I could not help but observe all the birds that dwell and migrate in and out of the landscape. I love to watch them, how they fly, feed and roost. They are impossible to ignore. I’m not interested in counting them, but I like to know their names.

Sometime during these observations I began to think of them as the poet Rainier Maria Rilke’s angels, which have fascinated me for a long time. Rilke’s angels bear witness to the world much like poets and painters do. His angels are also points of inspiration. They are “Creation’s spoiled darlings, ranges, summits, dawn red ridges of all beginnings” he wrote, and “They are mirrors, drawing up their own out-streamed beauty into their faces again.” They are also reflections, “nowhere beloved, will world be but within us.”

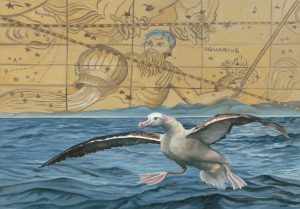

The Angels represent perfect consciousness and are known only through the psyche, as they attempt to keep life open toward death. In the second elegy of The Duino Elegies, Rilke wrote, “Every Angel is terrible still though, alas, I invoke you, almost deadly birds of the soul.” That last phrase “birds of the soul,” became the metaphor for a whole new series of bird paintings. The birds are angels, they are birds of the soul and they can carry a lot of metaphoric weight and are laden with mysteries. Rilke’s angels unite life and death in art.

I call my paintings “metaphoric realism.” They are not real in the natural sense, but they feel real. This requires seeking visual equivalents in the natural world for the vision within, and the birds or angels were flying all around me and within me and Rilke was there to help me identify them. In fact the tittles of the first seven paintings I will show you are lines from Rilke’s poems.

14 (“The Distance Between Two Doors”)

14 (“The Distance Between Two Doors”)

Rilke wrote: “Time passes through us, or we pass through it as guests to God’s wheat, in a previous present, a subsequent present, just like that, we are in need of a myth to bear the burden of the distance between two doors.” This large Blue Bird is so full of life and love that she can hardly fit through the door. She passes from the light before to the dark beyond under an egg-blue sky.

15. (“May Humble Weeping Bloom”)

15. (“May Humble Weeping Bloom”)

Another Rilke line, this one from the 10th elegy, captures a Kingfisher perched in a wetland, weeping the loss of what he observes, and perhaps a mate, and blooming in the sense that mourning is an incessant discourse with the departed one in order to draw him nearer. The work of mourning can produce a transformation into a new realm of visibility something is not just taken away, but is gained in a way never before experienced. I had become more than I was, an expanded container of my beloveds’ essence.

16. (“How Dear the Nights of Grieving”), also from the 10th Elegy, identifies the posture of this little phoebe that looks within to bear its burden of grief. This painting is another way of identifying the grieving process I just described.

16. (“How Dear the Nights of Grieving”), also from the 10th Elegy, identifies the posture of this little phoebe that looks within to bear its burden of grief. This painting is another way of identifying the grieving process I just described.

17. (“Creations Spoiled Darlings”)

17. (“Creations Spoiled Darlings”)

What else could I call the always enchanting but often vicious hummingbirds? They are articulations of light and awe. They inspire ecstasy. They are a life force above us and beyond us as they play with our souls.

In order to suggest the extended consciousness of the dead, Rilke asks one to “Be able to see the cry of a bird and hear by means of the soundless flight of the owl”. This owl is like a ghost or spirit to me, it can move among the living and the dead, it is a presence that occurs during the soul’s nightly flight.

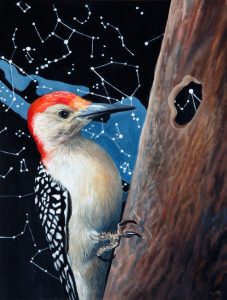

19. (“Neither Here Nor Beyond”)

19. (“Neither Here Nor Beyond”)

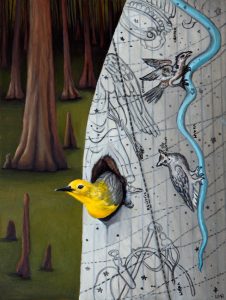

“There is neither a here nor a beyond but the great unity, in which these creatures that surpass us, the angels, are at home,” Rilke wrote. The Red-Bellied Woodpecker is neither here nor beyond. He is situated between a magical tree and a star chart. After I finished about a third of these bird paintings, I realized that they are often like my patients in palliative care, and the patients were helping me paint them. Many of the patients I see are neither here or beyond. They are between worlds.

They are intermediators like this prothonotory warbler and this one:

21. (“Lunar Warbler”) a lunar warbler.

21. (“Lunar Warbler”) a lunar warbler.

This angel has human attributes: she’s part avian and part woman. She is another angel in transition passing beyond nature. The older I get and the more I experience the loss of beloveds, the more often I feel a flow of currents between the living and the dead, and I find it consoling.

23. (“Seraph wrapped in a Veil of Light”)

23. (“Seraph wrapped in a Veil of Light”)

I have projected onto these angels an infinite consciousness, one that embodies the highest attributes of being. They are beings, like Rilkes’ angels, in whom thought and action, insight and achievement, will and capability, the actual and the ideal are one. They are wrapped in a veil of light, one that captures love.

This angel is transcending herself. Every soul is and becomes that which she contemplates. Some of these angels are straining toward the divine.

There is a human striving, a curiosity that seems timeless. In this painting I thought of ancient images of the Ibis and how that image has been transformed through time and also how it has remained the same. We all search for meaning in life and we explore the world and ourselves to experience and live out our capacities fully.

One wants to sense the divine spark in one’s being on a grand scale and these two paintings are metaphors for traveling in space and time like the angels.

Our lives pass in transformations, here an angel, a whooping crane, is transporting a soul to another world, much like medieval angels carried souls to heaven in what looks today like a diaper. These angels can transport patients away from tubes and ports and punctures and they can guide them during their transitions.

Recently I entered a room and discovered a very nice, bright woman in her late sixties, who had been a nurse before she became ill. She wanted to talk and she told me about her four children and ten grandchildren. She liked to work in her yard and she loved flowers. I asked her if there was something I could draw for her. She couldn’t think of anything, but she wanted me to draw something. I gave her a list: flowers, birds, animals, her children, angels. “An angel,” she said, “my angel is elegant, joy and peace”. After I started drawing her an elegant angel, she dozed off. I worked hard on this angel. She was tall and slim, with large wings and flowers falling from her hands. I wanted her face to resemble the patient’s lovely countenance. When I finished, I held the drawing in front of her and spoke. She looked up and saw her angel and seemed astonished. She held the sketchbook to her chest and said, “That’s my angel.” Then she told me that her grandson had asked her three days ago if she had seen any angels yet and that had startled her. She hadn’t quite accepted her departure. It seemed to me that the elegant angel she had conjured up was going to be her guide, and was offering her joy and peace.

Sometimes I feel the souls of my dead, like distant visitors, neither dead nor alive, more like a bird passing through me.

All of these paintings are an artistic response to sorrows and deep distress. To regret and loss. They also offer hope and visions of transformations, love and light. They attempt to make the invisible visible, and offer a vision of a transitory life that reveals my unspoken story.

Thank you