Selected Presentations

- The Soul’s Eye: Art in the life of people with terminal illness

The Fourth Annual Symposium "The Collective Soul", January 30 -31, 2015, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center - Unspoken Stories

Houston Seminar, February 2013 - Modest Witness: A Collaboration with Donna Haraway, 2009

- Cyborgs, Wonder Woman and Techno-Angels: A Series of Spectacles

Center for the Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, 1996 and Arizona State University, February 1998 - Between Cultural Eras: The Effects of Postmodern Thinking on the Modernist Concept of Regionalism

College Art Association 83rd Annual Conference, San Antonio, Texas, January, 1995 - The Ilusas (deluded women): Representations of women who are out of bounds

Presentation for the Society of Institute Fellows at the Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 1993 - Secular Uses of Traditional Religious Images in a Postmodern Society

Women's Caucus for Art, February 1991

Secular Uses of Traditional Religious Images in a Postmodern Society

Women's Caucus for Art, February 1991

by Lynn Randolph

“Religion, it has frequently been said, both articulates and responds to the life experience, the ideas and the ultimate concerns of human beings and communities.” (1) These lines from Margaret Miles’ book, Image as Insight, give voice to feelings I have about religion as being broader and deeper than either most instituted religions or the secular world perceive it to be. To me, the history of religions is largely one of domination and repression; from the threats to Galileo which forced him to renounce the evidence of his own eyes to Salman Rushdie’s fugitive life, from two hundred years of the horrors of the Inquisition to the current indifference of many churches to the continuing tragedies of AIDS. It is less than five hundred years since the Council of Trent where the Catholic Church finally declared that women have souls.

But this is only one side of the question. I am also aware of the involvement of churches in the sanctuary movement, protecting Central American refugees, and numerous other “good works” done by religious groups. I think the issue of religious beliefs makes many of us who lead secular lives in a largely secular society feel ambivalent, at times torn, and sometimes embarrassed .Much of what we as feminists and artists are trying to overcome originated in the early discourse of religion.

Ecclesiastical rule marked the beginning of the production of master narratives including the canons of art. Religious images simultaneously express some of our most noble ideals and our most debased behavior. Notions of sacrifice, transcendence and elevation are double-edged. Many lives have been needlessly sacrificed in the name of some god and many have been enslaved, like the indigenous population of South America.

Perhaps in attempting to lift our eyes above our own conditions, we have been blinded, intimidated, and diminished. Since we help to create each other, as we continuously produce and reproduce, our common culture, I see little reason to hand over rich and powerful images to those who stand for all that threatens to make religions instruments of oppression and destruction. To the contrary, I think that religion can be a vital re-source for making art and constructing a life. This, of course, involves an expanded sense of religion, one which articulates and responds to the deep human experiences, the ideas and the ultimate concerns of being human in the late 20th century; a sense of religion that is enhanced by broadening and making relevant religious texts and images.

One very interesting development in biblical studies was the discovery in 1945 of some “gnostic” texts in upper Egypt at Nag Hammadi. Elaine Pagels’ book (2) on these secret teachings offers us a view of God that is distinctly different than those projected by more conventional expressions of the Judaic-Christian tradition, who insist that a wide chasm separates humanity from its creator, that God is wholly “other.” The gnostics believed that self knowledge is knowledge of God, that the self and the divine are identical. Pagels defines gnosis as “insight,” an intuitive process of knowing oneself. She points to the shared premises that many of the gnostics have with contemporary psychotherapy. Both agree, in contrast to orthodox christianity, that the psyche bears within itself the potential for liberation or destruction. Few psychiatrists would disagree with the words attributed to Jesus in the Gospel of St. Thomas, “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will serve you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you. Such insight comes gradually, through effort. Recognize what is before your eyes and what is hidden will be revealed to you.”

This pursuit of gnosis, or knowing god through a consciousness of the vast cosmos within ourselves, is the path that the late Joseph Campell attempted to teach. He, too, believed that self awareness and spiritual growth is a solitary and difficult process, with many internal resistances struggling to remain unconscious. For him the relationship between art and religion is immediate. “Art,” he wrote, “Literature, Myth and Cultural philosophy and ascetic disciplines are instruments to help the individual past limiting horizons into spheres of ever- expanding realization.” (3)

Similarly, Pagels compares artists to the gnostic view that original creative invention is the mark of anyone who becomes spiritually alive. The gnostics, she observes, “like artists, express their own insight, their own gnosis by creating new myths, poems, rituals, dialogues with Christ, revelations and accounts of visions.” They also believed that all who received gnosis had gone beyond the teachings of the Church and had transcended the authority of its hierarchy.

Simone Weil, the much revered French mystic writer and political activist wrote something that helped me define my own feelings about the church. She wrote, “You can take my word for it too, that Greece, Egypt, ancient India, and ancient China, the beauty of the world, the pure and authentic reflections of this beauty in art and science, what I have seen of the inner recesses of the human heart where religious belief is unknown, all of these things have done as much as the visibly Christian ones to deliver me into Christ’s hands as his captive. I think I might say more. The love of those things that are outside visible Christianity keeps, me outside the church.” (My emphasis, L.R.)(4)

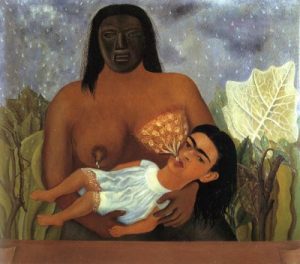

Much of the Imagery that we inherited from early christian art, to and through the Renaissance, is aesthetically beautiful, but also reflective of our “official” history and culture. As such, its attachment to only one story or master narrative has limited us to a narrow range of interpretations, burdening us with images that have reduced, and essentialized the total life experience, to versions of the life of Christ. (I suspect this could also be said of Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and Jews.) For example there are thousands of images of the Madonna and child, Mary holding and, most typically, looking adoringly at the Christ child. Where, one might ask, are there images of a fearful, tired, playful, questioning, etc., mother? I think Frida Kahlo’s painting, My Nurse and Me,” [slide.] is unique in the way it represents the mother-child relationship to us. The Mother wears a dark mask, the hidden ancestor, the child has an adult head. There is no emotional bond between them, Instead, the milk that rains down from the sky could also be the source of milk dripping into Frida’s mouth. To me this is a religious painting, because it brings forth a deep feeling that was within the artist and now connects to the experience of others.

Much of the Imagery that we inherited from early christian art, to and through the Renaissance, is aesthetically beautiful, but also reflective of our “official” history and culture. As such, its attachment to only one story or master narrative has limited us to a narrow range of interpretations, burdening us with images that have reduced, and essentialized the total life experience, to versions of the life of Christ. (I suspect this could also be said of Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and Jews.) For example there are thousands of images of the Madonna and child, Mary holding and, most typically, looking adoringly at the Christ child. Where, one might ask, are there images of a fearful, tired, playful, questioning, etc., mother? I think Frida Kahlo’s painting, My Nurse and Me,” [slide.] is unique in the way it represents the mother-child relationship to us. The Mother wears a dark mask, the hidden ancestor, the child has an adult head. There is no emotional bond between them, Instead, the milk that rains down from the sky could also be the source of milk dripping into Frida’s mouth. To me this is a religious painting, because it brings forth a deep feeling that was within the artist and now connects to the experience of others.

I think that a breaking down of hierarchical systems, by fusing them with other systems offers us a way to delegitimate and disorient prevailing structures of power, while, at the same time, inserting the values of the oppressed and marginalized. Thus, to create art that redistributes suffering, that empowers the image of women, magnifies dreams, ennobles the image of the outsider and the marginalized, and generally inverts hierarchies is to intervene in the history of the present. Our task is to imagine, not merely new styles, but new visual languages that recover that which has been deformed or marked by the dominant institutions of culture as unacceptable, to articulate a vision of the world that is inclusive.

The recent dialogues in new critical thinking, both by revisionists and theorists in many disciplines have much to offer our discussions. Their ideas seem to have more to do with intellectual strategies than with any concrete theories. For example, many are learning to ask the questions pushed forward by the work of Jacques Derrida — Who is speaking for whom and what location are they speaking from? In whose interest does this discourse work? Who is representing whom? Who is silenced? By whom? By learning to ask these questions of texts and images, we learn to speak the unspeakable.

The recent dialogues in new critical thinking, both by revisionists and theorists in many disciplines have much to offer our discussions. Their ideas seem to have more to do with intellectual strategies than with any concrete theories. For example, many are learning to ask the questions pushed forward by the work of Jacques Derrida — Who is speaking for whom and what location are they speaking from? In whose interest does this discourse work? Who is representing whom? Who is silenced? By whom? By learning to ask these questions of texts and images, we learn to speak the unspeakable.

Latin American culture, particularly Mexico’s, is a good example of the fusing of different systems to create still richer forms. Though the Indians were forced to learn Catholicism, its symbols and codes, they managed, in many instances, to incorporate their own colors, designs, as well as rituals, into their new “Christian” lives. In the 19th century, Mexican artists painted small religious images on tin. Some of these represented incidents in the lives of a saint, Christ, or the Virgin. These are known as Retablos (or altar pieces). They were household Gods who were placed around personal altars and appealed to for good health, fertility, an abundant crop, and everything else. [slides.]

Ex Votos are also small paintings on tin and these are personalized in a different way; they are offerings of thanks given in gratitude for miraculous favors. In the top portion the image of the saint or holy person who granted the favor is depicted. In the center, the disaster, serious illness, or other unfortunate event is represented. At the bottom, a text describes the event and offers thanks. These were nailed to the walls of local churches, as well as the walls of homes. [slides.] Some images came from the New World. One called “el Mano Poderoso” or “The Powerful Hand,” [slide.] always represents the Holy Family or Mary, Joseph, and a young Jesus with Joachim and Anne. My version includes everyone. [slide.]

Ex Votos are also small paintings on tin and these are personalized in a different way; they are offerings of thanks given in gratitude for miraculous favors. In the top portion the image of the saint or holy person who granted the favor is depicted. In the center, the disaster, serious illness, or other unfortunate event is represented. At the bottom, a text describes the event and offers thanks. These were nailed to the walls of local churches, as well as the walls of homes. [slides.] Some images came from the New World. One called “el Mano Poderoso” or “The Powerful Hand,” [slide.] always represents the Holy Family or Mary, Joseph, and a young Jesus with Joachim and Anne. My version includes everyone. [slide.]

The art of some contemporary Latin Americans, as well as some of their neighbors across the border in the Southwest of the U.S., fuses myth, history, religion, popular culture and current events. In 1984, when I saw no visible signs of compassion for the suffering people of Central America, especially the “disappeared” in El Salvador and Guatemala, I had a vision of an angel, whose wings of mercy covered their bodies. [slide.] I’ve used the angel as a metaphor for goodness, compassion, and suffering. [slides.] Recently, I’ve tried to combine old metaphors and myths like angels and demons with current concerns and issues. I’m also using some formal devices from traditional religious art like the borders in medieval manuscripts which reference the subject in the illumination. My small scale retablos are an attempt to paint what many think of as political, social, and economic concerns in a spiritualized context. [slides.]

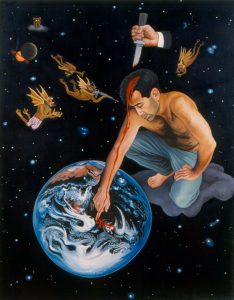

One recent painting, entitled “Credo,” [slide.] uses Fra Angelico’s image of St. Peter,the Martyr as one of its sources. In the Fra Angelico, St. Peter, who is stabbed in the head, writes with his own blood on the ground, “Credo i deu R” (I believe in God the King). The young man in my painting is stabbed in the head by the Multi-national Corporate hand of God. Medieval demons circle him with an AK-47, dollar bills, and political uniforms. The young man, from his position in outer space, writes “Credo..” (I believe—) on the Earth in his blood; his belief is not a given, it is in the process of happening.

One recent painting, entitled “Credo,” [slide.] uses Fra Angelico’s image of St. Peter,the Martyr as one of its sources. In the Fra Angelico, St. Peter, who is stabbed in the head, writes with his own blood on the ground, “Credo i deu R” (I believe in God the King). The young man in my painting is stabbed in the head by the Multi-national Corporate hand of God. Medieval demons circle him with an AK-47, dollar bills, and political uniforms. The young man, from his position in outer space, writes “Credo..” (I believe—) on the Earth in his blood; his belief is not a given, it is in the process of happening.

In what might be called a post-paradigmatic world, that reaches unprecedented levels of complexity, persistent change, and multi-layered pluralism, many of us find that the most constant factor in our lives is ourself. And so it may be that the self is the sacred ground in a postmodern society from which we form our values, including our understanding of the other as a self also struggling with self consciousness, also struggling to find what it is to be. This paper is not just about secular ethics or secularizing the spiritual. It is a call to not be afraid or embarrassed to spiritualize the secular, or to encompass the non-rational truths in our lives and art.

Presented at the panel on “Religion as a Re-source,” at the National Meetings of the Women’s Caucus for Art. Washington, D.C. February, 1991

SLIDES

[1] My Nurse and Me. — Frida Kahlo

[2] Retablos — St. Raymond

[3] Ex Votos —

[4] The Powerful Hand

[5] My Powerful Hand

[6] The Merciful Angel

[7] Angels — Surviving, Fallen,

Inconsolable, and U.S. Peace Plan.

[8] Recent slides (3)

[9] The Shepherdess

[10] Credo