Essays

The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inapproriate/d Others

by Donna Haraway

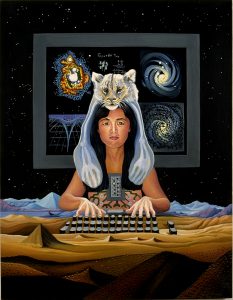

The final image of this excessive essay is “Cyborg”, a 1989 painting by Lynn Randolph, in which the boundaries of a fatally transgressive world, ruled by the subject and the object, give way to the borderlands, inhabited by human and unhuman collectives. These borderlands suggest a rich topography of combinatorial possibility. That possibility is called the earth, here, now, this elsewhere, where real, outer, inner, and virtal space implode. The painting maps the articulations among cosmos, animal, human, machine, and landscape in their recursive sidereal, bony, electronic, and geological skeletons.Their combinatorial logic is embodied; theory is corporeal; social nature is articulate. The stylized DIP switches of the integrated circuit board on the human figure’s chest are devices that set the defaults in a form intermediate between hardwiring and software control–not unlike the mediating structural-functional anatomy of the feline and hominid forelimbs, especially the flexible, homologous hands and paws. The painting is replete with organs of touch and mediation, as well as with organs of vision. Direct in their gaze at the viewer, the eyes of the woman and the cat center the whole composition. The spiraling skeleton of the Milky Way, our galaxy, appears behind the cyborg figure in three different graphic displays made possible by high-technology visualizing apparatuses. In the place of virtual space in my semiotic square, the fourth square is an imaging of the gravity well of a black hole. Notice the tic-tack-toe game, played with the European male and female astrological signs (Venus won this game); just to their right are some calculations that might appear in the mathmatics of chaos. Both sets of symbols are just below a calculation found in the Einstein papers. The mathmatics and games are like logical skeletons. The keyboard is jointed to the skeleton of the planet earth, on which a pyramid rises on the left mid-foreground. The whole painting has the quality of a meditation device. The large cat is like a spirit animal, a white tiger perhaps. The woman, a young Chinese student in the United States, figures that which is human, the universal, the generic. The “woman of color,” a very paraticular, problematic, recent collective identity, resonates with local and global conversations. In this paintinig, she embodies the still oxymoronic simultaneous statuses of woman, “Third World” person, human, organism, communications technology, mathematician, writer, worker, engineer, scientist, spiritual guide, lover of the earth. This is the kind of “symbolic action” transnational feminisms have made legible, S/he is not finished.

The final image of this excessive essay is “Cyborg”, a 1989 painting by Lynn Randolph, in which the boundaries of a fatally transgressive world, ruled by the subject and the object, give way to the borderlands, inhabited by human and unhuman collectives. These borderlands suggest a rich topography of combinatorial possibility. That possibility is called the earth, here, now, this elsewhere, where real, outer, inner, and virtal space implode. The painting maps the articulations among cosmos, animal, human, machine, and landscape in their recursive sidereal, bony, electronic, and geological skeletons.Their combinatorial logic is embodied; theory is corporeal; social nature is articulate. The stylized DIP switches of the integrated circuit board on the human figure’s chest are devices that set the defaults in a form intermediate between hardwiring and software control–not unlike the mediating structural-functional anatomy of the feline and hominid forelimbs, especially the flexible, homologous hands and paws. The painting is replete with organs of touch and mediation, as well as with organs of vision. Direct in their gaze at the viewer, the eyes of the woman and the cat center the whole composition. The spiraling skeleton of the Milky Way, our galaxy, appears behind the cyborg figure in three different graphic displays made possible by high-technology visualizing apparatuses. In the place of virtual space in my semiotic square, the fourth square is an imaging of the gravity well of a black hole. Notice the tic-tack-toe game, played with the European male and female astrological signs (Venus won this game); just to their right are some calculations that might appear in the mathmatics of chaos. Both sets of symbols are just below a calculation found in the Einstein papers. The mathmatics and games are like logical skeletons. The keyboard is jointed to the skeleton of the planet earth, on which a pyramid rises on the left mid-foreground. The whole painting has the quality of a meditation device. The large cat is like a spirit animal, a white tiger perhaps. The woman, a young Chinese student in the United States, figures that which is human, the universal, the generic. The “woman of color,” a very paraticular, problematic, recent collective identity, resonates with local and global conversations. In this paintinig, she embodies the still oxymoronic simultaneous statuses of woman, “Third World” person, human, organism, communications technology, mathematician, writer, worker, engineer, scientist, spiritual guide, lover of the earth. This is the kind of “symbolic action” transnational feminisms have made legible, S/he is not finished.

We have come full circle in the noisy mechanism of the semiotic square, back to the beginning, where we met the commercial cyborg figures inhabiting technoscience worlds. Logic General’s oddly recursive rabbits, forepaws on the keyboards that promise to mediate replication and communication, have given way to different circuits of competencies. If the cyborg has changed, so might the world. Randolph’s cyborg is in conversation with Trinh Minh-ha’s inappropriate/d other, the personal and collective being to whom history has forbidden the strageic illusion of self-identity. This cyborg does not have an Aristotelian structure; and there is no master-slave dialectic resolving the struggles of resource and product, passion and action. S/he is not utopian nor imaginary; s/he is virtual. Generated along with other cyborgs, by the collapse into each other of the technical, organic, mythic, textual. and political, s/he is constituted by articulations of critical differences within and without each figure. This painting might be headed, ” A few words about articulation from the actors in the field.” Privileging the hues of red,green, and ultraviolet, I want to read Randolph’s Cyborg within a rainbow political semiology, for wiley transnational technoscience studies as cultural studies.

We have come full circle in the noisy mechanism of the semiotic square, back to the beginning, where we met the commercial cyborg figures inhabiting technoscience worlds. Logic General’s oddly recursive rabbits, forepaws on the keyboards that promise to mediate replication and communication, have given way to different circuits of competencies. If the cyborg has changed, so might the world. Randolph’s cyborg is in conversation with Trinh Minh-ha’s inappropriate/d other, the personal and collective being to whom history has forbidden the strageic illusion of self-identity. This cyborg does not have an Aristotelian structure; and there is no master-slave dialectic resolving the struggles of resource and product, passion and action. S/he is not utopian nor imaginary; s/he is virtual. Generated along with other cyborgs, by the collapse into each other of the technical, organic, mythic, textual. and political, s/he is constituted by articulations of critical differences within and without each figure. This painting might be headed, ” A few words about articulation from the actors in the field.” Privileging the hues of red,green, and ultraviolet, I want to read Randolph’s Cyborg within a rainbow political semiology, for wiley transnational technoscience studies as cultural studies.