Essays

In Relief

by Linda DeFeo

Translation from the Italian by Tom Berth

Translation from the Italian by Tom Berth

Quadernidialtritempi.eu. no. 24-2010

“The Mysteries of Lynn M. Randolph between Obsessive Metaphors and Promising Monstrosity.”

The poet is a pretender. He pretends so completely that he succeeds in pretending that it’s pain – the pain that Fernando Pessoa actually feels

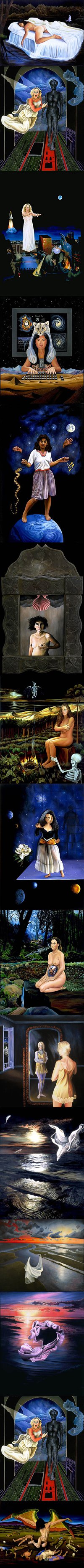

The visionary and metaphorical realism of the paintings of Lynn Randolph reinterprets symbols, icons, myths, representing material processes, perceiving the urges of an inescapable anthropological mutation, deciphering unfiltered reality in bloom in the natural-cultural world and foretelling the model of future humanity. This “outsider” artist, as she herself loves to define herself, drawing inspiration from literary tropes and philosophical reflections, from the heights of aesthetic theory to expressions from popular culture, she delineates the relations of confluent exchanges between experiences of the political and the socio-morphic representation of the cosmos, to underline man’s extreme defectiveness, constitutionally foreign in a world deprived of objective meaning.

Randolph splendidly weds, in the magic of the everyday sketched out, of the dream depicted, objects represented, the influence of late Medieval and early Renaissance painting, and the influence of artists such as Man Ray, Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo. Anchored beyond that in a disturbing recollection of the graphic writings of authors such as Edgar Allan Poe to the echo of novelists such as Philip K. Dick, James G. Ballard, Thomas Pynchon and of directors such as George Romero and Ridley Scott, masking, along the same lines as cybernetic punk heterogeneity, the traits that define the hyper-contemporary media landscape.

Retracing the paths of a technique that obsessively challenges its own limits, the painter welcomes the danger that the dynamic of emancipatory decentralization of the processes of communication might not find an adequate reflection in the stubborn affirmations of archaic and imperialistic models of hierarchical power. Giving form to signifieds, instruments and tropes of technoscience, Randolph delineates on the artistic plane that cultural universe, analyzed on the philosophical plane by Donna J. Haraway, transformed in an integrated cycle where individual, technology, libertarianism and politics weave themselves into a complex discursive matrix.

Acute political protests against military repression vibrate across the representation of creatures such as Merciful Angel, painted in 1984, from the imposing and colorful wings, fallen among pieces of corpses and skulls strewn about the battlefields, or of the winged woman, mortally wounded, smeared with blood, of U.S. Peace Plan, of 1990. The heavenly entities transform themselves in Annunciation of the Second Coming, from 1996, into the messenger with transparent wings—appearing on the cover of the Harawayan text Modest_Witness@FemaleMale_Meets_OncoMouse™–soft feminine figure, announcing the arrival of the Redeemer, an arcane image, inorganic, fantasmic, composed of silicon, chips and data, of digitized corporeal surfaces, that risk the night, but without avoiding the risks tied to the dream-nightmare of a technological transcendence of the body. Randolph shows how this latter, in order to integrate itself perfectly with intelligent machines, reconfigures itself, sorting the transformation of the man-form, the realization of synthetic organisms, the integration therefore of the synthetic capacity of the traditionally human mental functions with those analytical ones of artificial intelligence and dissolving the dependence of thought upon a specific physical structure (cf. Caronia, 1996, p. 55).

The painter produces the fantasies of disembodied immortality, considered from biological cybernetics, which, celebrating a world in which mental structures are preserved as potentially eternal information models (cf. Moravec, 1998, p. 17), deny the rootedness of man in a material universe of extreme complexity (cf. Hayles, 1999, p.5) and ignore the body as the seat of being, looking for the substitution with a custodian of the bits that form its structure, a symbiote of the code, last precipitate of the assimilation realized of homo technologicus (cf. Longo, 2003, p.84), in extreme restriction of matter, now indifferent. And it is from the communication between body, mind and signs of the machine that give birth to the re-figuration of surreal beings attached to the technico-medical image of the frontal sections of the cranium in the self-portrait Immeasurable Results, of 1994, inspired from an advertisement for a magnetic resonance machine by Hitachi, a company that produces instruments for computerized medical visualizations, in which Randolph places herself lying down under the screen that projects diagnostic images and psychic levels, aware and unaware, the lived experience that continues living, the flux that exceeds its representations and causes syntax to break out, the erlebnis (experience), not reducible into simple elements, not measurable with machine computerized calculations. The painting seems to want to underline that intelligence, if conceived as mere abstract and logico-formal entity, does not point to the historical being in the world, and that intelligibility, with its humus of un-objectifiable beliefs, is never completely mathematizable, just as knowledge and signifying actions are not totally formalizable, nor insertable in theories and expressible using systems of rules. Subverting the conventional polarization of intellect and body, knowledge and matter, Randolph reveals the invisible, the unmovable substratum of life, the sphere of the pre-reflective, and radicalizes its own symbolism in the frequent appearance of archetype-images of the unconscious, present in humanity since ancient times, destined to represent phenomenal and psychical reality, images that in and for their being beyond thought are abundantly fed with productive alterity. Randolph’s figurative research delineates, with lyrical tragicality, dreamlike horizons on which are paradoxically strewn objects taken out of their original contexts, hybrid universes affected with contamination between the organic world and the machine world, states of putrefaction, with bodies crossed with adulterated livestock or torn by electronic artifacts, emblematic representations of a nature prodigiously empowered and dramatically tormented, that suggests flight towards alien worlds and unfamiliar stars: we are dealing with dreams which, more than occupying sleep, aim to wake up the sleeping, given the surprising quantity of revelations of so-called authentic reality, never ultimate, always penultimate, in perennial becoming, actually configured, according to the painter, in a most intricate network of connections, able to weave together ideologies, signs and needs of the collectivity.

Randolph’s canvases bring together, with expressive vigor, powerful material vibrations and vivid chromatic sfumature (shadowiness), holding them in airy views, while silent skies and enchanted places penetrate those who arrive, realizing an instinctive synthesis between a naturalistic and a metaphorical scene. Struck by the appeal of the planet, caught up in its charm and restored in scenographic visions of the whole or in magical minimal descriptions, the artist renders the intensity of the impression with a wild incisiveness of luminescent obscurity, of velvet blacks or iridescent blues, which flourish in manifestations of primordial life, of the fecundity of nature, as in Life Within, of 1984: phenomena that become universal symbols of revelations and transformations, of power and spirituality. The daring discoloring of the greens into blues, crossed by intense flames of solar colors, couches the theme of the immersion of man in a natural sacredness, of the eternal cyclicity of the cosmic order, while, in the decomposed figures, arbitrary perspectives are drawn and, in improbable places, the usual becomes absurd. Among inflamed reflections the spectacle makes itself vibrating, generating amazement and awe, and, among the emotive resonances, the eye loses itself in a transgressive and outlaw universe. The evanescent light that enlightens the works of Randolph or the transparent shadow that veils them insinuates themselves in the palpitating pathos of the scenes, to the point of offering hints of fervid metaphysical imaginings, mindful of the past, rooted in the hic et nunc (here and now) yet extended towards a hoped for future through desire, discovery, anxiety, a part of the game of remaining present and of the expressive adventure.

The theme of nature is interpenetrated with that of death, such that it is not only a case that tends to co-nature (equate in binomial terms) being with not being, letting filter, in the waning of the sun, a ray of unhealthy awareness. Among luxuriating woods and passing clouds, sparkling constellations and desolate plains, Randolph manages to show the way of the human pilgrim on the margins of the path of existence, gripped in the jaws of entropy, enrapturing the soul’s eye with canvases such as Memento Mori, of 2000, or Lamentation, of 2001, and evoking dramas that prevent ignoring the monstrosities, already foreshadowed in paintings such as Presiding, of 1991, on the tragedy of time, destined not to unravel her own threads anymore, not to flow anymore, not to explain, not to illuminate new days, time of the fateful shadow, total oblivion, the ultimate mystery in which hope is erased and knowledge enervated. The painter captures luminous reverberations, collecting from them, with a poetic feeling, infinite vitality, and she sets them in an exuberance of a tonality able to render the fleeting effect of a never-blinding-brilliance in the mythical world of mortal heroines, that cross the semi-divinity of the world, of the air, of water, of fire, not as mere ideal representations, but as specific characterizations of real women, fluctuating among organic nebulae, similar to uteruses, in the uneasy anticipations of Skywalker Biding Through, of 1994, or roving over the dissolute urban chaos in the horrific final game of Somnambulist Mall-walking, of 1995, while inedited, complexes and protoform identities forge themselves. To play (scheme) this way with the self requires an intertwinement of ontologically deformed entities, a complicated matrix of brain, body and technology, that constitute that which should properly be identified as “our selves” (Clark, 2003, p. 27): the DNA helix of the woman and of her android clone, which affects its own bioelectronic artificiality, drawn in Self-Consortium of 1993, and even the serpentine spiraling of a galaxy that marks the threshold between internal space and external space, around which moves the hybrid, no longer so futuristic, self-consortium. The science-fiction dimension is contaminated with the intrusion of traditional christian iconography, in the drawing of divinity as the Mestiza Cosmica of 1992, a native of a frontier land, contemporary version of the Virgin of Guadalupe, that watches over the world, standing on the border between Mexico and Texas, astride the redesigned conditions of free trade agreements of the new world order and the politics against immigration carried on in the principal countries of the global economy. The holy metic (resident alien, mixed breed) reprises the persistent dualism of the western tradition, functioning in the logics and practices of dominion over women, over people of color, over workers, over nature, which is to say of the power over whomever becomes constituted as “other” tasked with reflecting the self (cf. Haraway, 1999, p.78). From the 18th century, the great historical constructions of gender, race and class were tied together in the bodies of women, of colonized peoples, of workers, marked from the organic point of view, symbolically others with respect to the fictional and rational self of the species-man, universal and therefore not marked. The cosmic mother with one hand holds at bay an adamantine rattlesnake and with the other handles the Hubble telescope, mediating between the natural and the technological, splitting herself on that organic-cybernetic horizon that she found, already in 1989, the year of the violence perpetrated at Tian’anmen, finding expression in the drawing of a Chinese girl student, the animal-humano-machine entity of Cyborg, taken in the suggestive and perhaps promising solitude of a lunar landscape, among twinkling galazies and mathematical formulas of Einstein’s theory of relativity and of chaos theory. This totemic image, anticipating new techno-political realities, and in a certain sense, a figure similar to that in A Diffraction, of 1992, a narrative, graphic, psychological and political diffraction, a transmutation that, metaphorizing the incarnation of multiple selves in a single body, with two heads, extra fingers, floating in metaphysical space, unlike the reflection, it doesn’t move the same elsewhere, but recounts a heterogeneous story, no longer concerned with the originals, a transformation that is accomplished in the face of the abyss of the unknown, in the threshold zone between the present and the future, and which no longer opposes the false to the true, but substantiates the production of new realities and new identities with appearances neither true nor false (cf. Frasca, 1996, p.23).

Randolph understands that the organic-inorganic binomial, conceived in merely dichotomous terms, yields an explanatory framework of the phenomenal plurality that animates the anthroposphere: human culture represents in fact the greatest participatory project that nature has managed to launch. Man belongs to a species that goes beyond “the mirror of the innate” thanks to the help and mediation of a variety of alterities, first among which is the animal one (cf. Marchesini, 2002, p. 69). The cultural process, interpreted as absolutely as an hybrid event, realizes itself according to various modalities: “the use of an instrument, partnership with another species, the conferral of significance, the proposition of a theory—in short all that which activates a conjugation with external reality or reference.” (ibid. p. 25).

The paintings of Randolph, hostile to technophilic euphoria, explore the aberrant effects issued from vertiginous and uncontrolled scientific progress, from the stubborn foolishness of medical experimentation in the therapeutic brutality of Managed Care, of 1996, operating on the basis of the dominion of economic priorities, that yields obscene happiness and offers spectacular spectacles of death, in a special-temporality in which the accomplishment of natural evolution seems broken, leaving in any case the individual caged in a physicality destined for extinction. Reduced to inextricable tangles of circuits, batteries, valves and bobbins, kept up by the activity of ticking machines, human beings, suffering, in their profound torment and their hard-headed cooperation, wait for death. The challenge is inane against the implacable triumph of human weakness, issued against the ongoing organic transformations, fruit of research on an artificiality that defeats the inevitable destiny of dissolution, unavoidable despite its distance, final stage of an individual path. Equipped with microchips, pace-makers and electro-catheters, or even furnished with artificial hearts and blood, pathetic “manufactured bastards” (Haraway, 2000, p. 34), that swallow up life or entrust it to a machine, facts of science and death, reduced to commodities down to their DNA while biotech companies rush to file patents, men follow their cyborg destiny, stamped on their circuits, gathering inedited opportunities, establishing new dependencies, prolonging existence, combating senselessness. The passion of chimerical hybrids is related, in all of its atrocity, in the drawing of the woman-mouse of The Laboratory, or The Passion of the OncoMouse, of 1994, the transgenic guinea pig presumed savior of the human race, become an object of transnational, technoscientific surveillance, if not an instrument that reconfigures biological knowledge, laboratory practices, economic fortunes, individual and collective hopes and fears. Site for the transplant of a human tumor gene that produces breast cancer, the first patented animal in the world, the OncoTopo™, model of transpacific research, is condemned to accomplish a counterfeit path of a life cycle, remodeled by the regulatory institutions of the global market. “The controversies surrounding the patenting and the commercialization of the “Harvard mouse” were at the center of attention in the popular and scientific press in Europe and in the United States. …April 12, 1988 the federal office of patents issued a patent to two genetic researchers, Philip Leder of Harvard Medical School and Timothy Stewart of San Francisco under the name of the president and administrators of Harvard College. The subsequent concession of the patent to E.I. Du Pont de Nemours & Co. for the commercial development became the highlight of the symbiosis between industry and academy in the field of biotechnology from the end of the 1970’s on. With the unlimited concession to Philip Leder for the study of genetics and cancer, Du Pont was one of the chief sponsors of the research. Du Pont made subsequent agreements with the Charles River laboratory Wilmington in Massachusetts for commercializing OncoTopo™. In its Price List of 1994, Charles Rivers published five versions of these mice carrying different oncogenes of which three led breast cancers. These mice can contract many kinds of cancer, but breast cancer was the one semiotically most striking in the press as in the original patent” (ibid. p.120).

New alterity, disturbing and unrecognizable, undefined and undefinable, OncoMouse seems to go beyond the future even before it has arrived, connected in a redone temporal flow, no longer resting on its supports, no longer based on the natural sequence of past-present-future. Redefined by its patented status, circulating commodity on the trade routes of transnational capital, fragment of enervated power in the flesh, coagulate of science, money and nature, the biotechnical and biomedical laboratory animal is a creature belonging to the kingdom of the living dead (cf. ibid. p. 119), a metaphor of mortality and a promise of existence. The oncogene transplanted in the planned rat, guaranteeing death, betrays spontaneous biochemistry, adulterates the identity and conditions its end. The implanted needs, the profitable agony, that inoculates death in the search for more life, the palpitating squeaks of the human mouse express the suffering of a sacrificial victim, icon of the pain drawn as a Christological image, with swollen breasts and a crown of thorns on its head, while living the mystery of the flesh, interjecting technology, investing progress, patenting developments, paying for failures, in a cruel form of alternative existence, that justifies the ferocity and sublimates the sadism.

The mystery that permeates, in its multiple declinations, all of Randolph’s work is revealed in this last one with expressive vigor through fantasized articulations of an aesthetic phrase building in which illusions and delusions unexplain themselves in a fertile imaginative logic. The energy that pulses in the chimerical bodies of the cyborgs or in the vampiresque figures represented in the horror of technoscientific rooms, such as one, infested with bats and their metaphorical weight, of Transfusions, of 1995, is not all that far from the force that hits disobedient bodies, lost beyond boundaries in orgiastic ecstasies, inspired by the mystical experiences of the Eleusinians, Mexican women, living in the 17th century, widows, orphans, prostitutes, refigured in an evocative series of small drawings and reproposed while they go beyond the bounds of their own body, as in the divine rebellion of Venus, from 1992, or they spread out on the sparkling whiteness of the solipsistic pulsing of eros, as in the shameless abandon of Alone in the Wetlands of Desire, of 1993.

Randolph’s painting is colored with naïve touches and immersed in surrealism, situating itself in the shadowy zone in which the glance pushes itself up to the limits between conscious and unconscious, simple surfaces and hidden depths, natural world and metaphysical universe, past, present and future, life and death, and to their reciprocal relations, strong and illogical. The narration solidly anchored to places and attached to objects is tempered during the most recent phase of her production in a rarified composition often inspired from Magrittian glances, in a sea of backgrounds that dissolve into memorable skies, illuminated by vermillion sunsets or silvery nights, penetrated by gloomy shadows or violet rays, and in the reference to those absent through the swirling drapes which at one time they were wrapped, as in the Shrouds of Light, of 2002, Spirit Cradle, of 2003, and again in Soul Sail, of 2006, or mediating the delicacy of harmonious silhouettes that hint of the human form as in Sacred Wedding in the Night, of 2002, and which, defying the laws of physics, levitate, fleeing upwards, floating on celestial and crystalline panoramas, while the view of the observer, dwelling on the ethereal transparencies, unchains itself from the force of gravity. Existence is here designated not as a graspable presence of a being in its unexplained appearance, but as an evocation, diaphanous promise of life, that lightly but stubbornly reaffirms itself, emphasizing its loss and reconstituting human permanence in its fragile origins, persistence already evoked moreover in the little angels that seems to want to protect the tender embrace of the innocent girls of Millennium Children, of 1992, hunted by a pack of hyenas, harassed by a clownish demon with a stomach in the form of a frightening death mask, kneeling on the banks of a polluted swamp, under vultures flocking on a dried up tree, smoking chimneys of a nuclear power plant and a view of Houston in flames and futureless.

Randolph’s painting is colored with naïve touches and immersed in surrealism, situating itself in the shadowy zone in which the glance pushes itself up to the limits between conscious and unconscious, simple surfaces and hidden depths, natural world and metaphysical universe, past, present and future, life and death, and to their reciprocal relations, strong and illogical. The narration solidly anchored to places and attached to objects is tempered during the most recent phase of her production in a rarified composition often inspired from Magrittian glances, in a sea of backgrounds that dissolve into memorable skies, illuminated by vermillion sunsets or silvery nights, penetrated by gloomy shadows or violet rays, and in the reference to those absent through the swirling drapes which at one time they were wrapped, as in the Shrouds of Light, of 2002, Spirit Cradle, of 2003, and again in Soul Sail, of 2006, or mediating the delicacy of harmonious silhouettes that hint of the human form as in Sacred Wedding in the Night, of 2002, and which, defying the laws of physics, levitate, fleeing upwards, floating on celestial and crystalline panoramas, while the view of the observer, dwelling on the ethereal transparencies, unchains itself from the force of gravity. Existence is here designated not as a graspable presence of a being in its unexplained appearance, but as an evocation, diaphanous promise of life, that lightly but stubbornly reaffirms itself, emphasizing its loss and reconstituting human permanence in its fragile origins, persistence already evoked moreover in the little angels that seems to want to protect the tender embrace of the innocent girls of Millennium Children, of 1992, hunted by a pack of hyenas, harassed by a clownish demon with a stomach in the form of a frightening death mask, kneeling on the banks of a polluted swamp, under vultures flocking on a dried up tree, smoking chimneys of a nuclear power plant and a view of Houston in flames and futureless.

The discourse of Randolph has as its object a politics that does not just translate into the protections of specific forms of social life, but even in the defense of life itself, that deconstructs therefore the dominion that power exercises through the principle of sovereignty. The living becomes the source of inspiration for a bio-politics, that begins with an idea of life note merely understood as a biological category, vertical line between birth and death, but interpreted in its complexity as a multidimensional phenomenon, discontinuous, layered, intermixed, contaminated with artificiality. The incarnation of the cyborg, generated by “technoscientific uteruses” (ibidem, p.41), imploded creature to the embryonic state, evades the usual physiological parabola, unhinges the process of replication from the biological reproductive plan, realizing itself in a world “with genesis” that could become a world “without end” (op. cit. 1999, p. 41), negating the origin of the original magma and the annihilation into the final dust. Residing in the techno-bio-power spatial-temporal regime, the cyborg follows less the terrains of “’life’ with its evolutional and organic rhythms, than ‘life itself’ of which the timeframes are intrinsically connected to advances in communication and reconfigurations of the system” (op. cit., 2000, p.40).

A political practice capable of sustaining life without suppressing it must presumable be sought in a marginal territory, where identity is able to include alterity, particularly of the technological type, in a very complex relationship, not reducible to a relation of pure opposition, as much as a nexus of reciprocal implications, that, given its problematics and dangers, requires being considered with special understanding. Turning away from sterile dichotomies, that oppose social theory to the realm of imagination, the material of thought to the truth of art, the painter lets her imaginative energy explode and converts it into a poetics of the body thanks to visual expressions of rebirth from a world of obscurity, evoking the plastic strength of man that, in inexhaustible conflictuality and in the infinite theory of contradictions reserved for him by existence, is called to reaffirm his own liberty and own responsibility at impart meaning to events, often senseless, and to make choices conscious of the daring process of technological advancement. Randolph concentrates the ethical interest, projected on a terrain of pragmatic relations, in the indissoluble know between individuality and universality, in the undefined slipping away of sense, precisely of the metaphor, quasi-obsessively recurrent in her work, in the rejection of the traditionalism of any philosophy of history, by showing the contrast between the autonomous power of the subject and its extreme marginalization, apocalyptic violence of macabre impulses, states estranged beyond time and space, gathering the ineludible ties between life and its representations, and celebrating art, independently of the forms that that assumes, high or low, elite or of the mass, sophisticated or trivial as that might be, as one of the privileged places for the communication of truth, as one among the noblest lies that consent the recognition of truth.

Bibliography:

— Caronia A., Il corpo virtuale. Dal corpo robotizzato al corpo disseminato nelle reti, Padova, Muzzio, 1996.

— Clark A., Natural-Born Cyborg. Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003.

— Frasca G., La scimmia di Dio. L’emozione della guerra mediale, Genova, Costa & Nolan, 1996.

— Gould S. J., Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, W.W. Norton, New York, 1989.

— Haraway D. J.,Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, New York, Routledge, 1991, trad. it. parziale di Borghi L., Manifesto Cyborg. Donne, tecnologie e biopolitiche del corpo, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1999.

— Haraway D. J., Modest_Witness@FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™, New York, Routledge, 1997, trad. it. di Morganti M., rev. di Borghi L., Testimone_Modesta@FemaleMan©_incontra_OncoTopo™, Milano, Feltrinelli, 2000.

— Hayles K., How We Become Posthuman. Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, Chicago-London, The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

— Haynes D. J., The Vocation of the Artist, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997.

— Longo G. O., Il simbionte. Prove di umanità suturava, Roma, Meltemi, 2003.

— Marchesini R., Post-human. Verso nuovi modelli di esistenza, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2002.

— Moravec H., Robot. Mere Machine to Trascendent Mind, Oxford-New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.