Essays

Yesterday Inventing Tomorrow: The Imagist Language of Lynn Randolph

by Walter Hopps

Catalog essay from Millennial Myths: Paintings by Lynn Randolph, Arizona State University Art Museum, 1998

At the approach of the year 1000 in Western civilization, alarming, even hysterical questions and forebodings arose, darkly coloring the thought and art of that time. Ideas of humanity’s place in existence and the cosmos were shaken. As another such historical moment approaches. Lynn Randolph’s paintings from the past decade offer ample evidence of similar trepidation. For roughly the past thirty years, Randolph’s art has depicted representational views of animals and human figures combined in dreamlike settings, depictions I identify as within the modern imagist tradition. Arising from her body of paintings of the last decade, the theme and the title of this exhibition, ‘Millennial Myths: Paintings by Lynn Randolph,” addresses the unsettling forces that surround our entry into the third millennium. In these works, Randolph develops an imagist language for re- defining our responses to this new era.

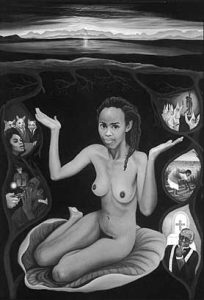

fig. 1

So?, 1993, Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 inches, Courtesy of the artist

Dark visions, often set in an indeterminate, inky astral space, encompass a diverse, foreboding subject matter Apocalyptic views of violence visited on women recur; in the painting “So,?” (fig. 1), 1993 , a naked and quizzical woman is surrounded by scenes of social brutality and political inquisition. The brutalizing effects of aberrant science are explored in “The Laboratory/ The Passion of OncoMouse”, 1994 (fig. 20), where the central figure becomes a woman/mouse mutant. In another group of paintings, the devastating impotency and terror provoked within patients by invasive medical experimentation are vividly depicted; in “Managed Care,” 1996 , the hapless male figure is splayed in an inverted cruciform position.

Each cautionary tale of terror nonetheless reveals some glint of hope through human understanding. This hope arises wherever the images provoke a fruitful spark of recognition in the viewer. In “Somnambulist Mall Walking,” 1995, a foreseeable horrific endgame is visualized that the prudent among us may then seek to avoid. In the painting “Millennial Children,” 1992, while

vicious hyenas, devils, and fires combine to threaten two young girls, tiny angels ally nearby to safeguard the inner peace and strength evinced by the endangered innocents. The lone male figure in “Credo,” 1990, beset by demonic figures of violence, is capable of connecting to the globe of the earth by inscribing in his own spilled blood a simple textual declaration of his faith in redemption.

Human frailty and the destructive forces society unleashes on its own most vulnerable members dominate the astral void and natural terrain, but the artist herself, through her willed confrontation with these terrifying environments and disquieting occurrences, seems to have devised a way out of the miasma. The very act of visualizing these images, of codifying these metaphors–the act of painting itself–provides the artist with a therapeutic balm: the conflicting forces are aligned into equilibrium on her canvas. The viewer who explores these dream locales thus may share in Randolph’s sense of closure, experi- encing the renewal that comes from directly confronting one’s demons. By awakening more humanistic responses, the artistes perception of primal chaos may yet yield harmony.

Randolph grew up in Port Arthur, Texas, near the Gulf of Mexico–as, coincidentally, did two other artists of renown, Robert Rauschenberg and Janis Joplin. Randolph seems to have come easily to a profoundly sensuous appreciation of natural phenomena. Perhaps a connection exists between her intrinsic sensibilities and the fact that the Texas Gulf Coast represents one of the major coastal wetlands for nourishing plant, fowl, and animal life forms. Yet, another topographical characteristic of the area is not natural but manmade: rising above the flatland is a vast array of petrochemical facilities that continually threaten the delicate ecology of this critical coastal plain. Much like Rauschenberg’s, Randolph’s response has been an abiding desire to preserve and nurture an in creasingly fragile nature; The opposition between technical or industrial forces and the natural phenomena they threaten forms a principal dynamic tension in Randolph’s representation of existence.

fig. 2

I Should Have Been a

Pair of Ragged Claws,

1971

Oil on canvas

50 x 40 inches

Courtesy of the artist

The first time I saw a work by Lynn Randolph was in 1971. I was the juror for a regional exhibition from the southwestern United States at the Oklahoma Art Center in Oklahoma City When I chose Randolph’s provocative portrait of a nude young woman sitting atop an oversized crab (fig. 2) for a purchase prize, the museum director pointedly asked me if I would consider changing my decision. I didn’t, and since that first encounter, I have followed the development of Randolph’s art with interest and enthusiasm. Her work has often been subject to the vagaries of censorship because her imagery depicts elements of the human erogenous zone, a place where each individual’s tolerance has a different threshold. Randolph has made a virtue of pushing the envelope of acceptability. The shock value of her subject matter is not intended to stir prurient interest, however but rather to force the viewer to deal more openly with his or her inhibitions. This method of discourse is an underlying construct of Randolph’s intentions: Her impatience with the status quo of a patronizing society invigorates her responses.

Since feminist ideas and issues are an abiding concern for Randolph, it was no coincidence that an unusually sensitive and prescient gallery owner, the late Bill Graham, represented Randolph (and a number of other women artists) at the W. A. Graham Gallery where, soon after I moved to Houston in 1983,1 was again intrigued to encounter Randolph’s work. Graham, who had worked with Man Ray in Paris, took a delectation in imagist painting. Likewise, Graham appreciated the affinity felt by many Texas artists toward their Mexican counterparts. Randolph has made this connection explicit in a scries of retablos and in her use of elaborate Mexican tin frames. Too great an emphasis can be placed on geographical influences, but there is no doubt that the artist, raised in Texas and living most of her life in Houston, plumbs a direct link to the mvths and images of Mexico and Central America. All of the aforementioned associations–eroticism, a feminist identity, a crossing of polite barriers, mythical and imag- ist depictions, and a strongly rooted geographical affinity between Texas and Mexico–form a consistent frame- work for Randolph’s paintings, shaping a complex and personal language of visual metaphor.

fig. 4 John James

Audubon, Great Blue

Heron from The Birds

of America, 1834

Aquatint engraving

on paper

39.5 x 26.5 inches

Private collection

Reviewing American art history, one can point to a number of precedents to Randolph’s paintings. The acuity of John James Audubon’s pictorial techniques (see fig. 4) led to an appreciation of naturalist causes in the mid-nineteenth century. An underlying agenda in Audubon’s rendering of birds and animals, though, was the sensuousness and luciousncss of the subject matter, used as a surrogate for sensual, even erotic emotions suppressed bv nineteenth-century society. In a similar fashion, Georgia O’Keeffe’s pioneering modernist works, especially those depicting natural forms, often carry a sexual charge. Randolph’s various creatures and flora portray recognizable natural forms, but thev also readily evoke sensuous associations. For the artist, these sensual scenes assert the primacy of the life force.

Randolph’s surfaces, her handling of paint, and her affinity for dream-state subject matter also suggest comparisons with the work of a number of Surrealist artists. Meret Oppenheim portrayed an erotic realm in the larger body of her work–not just in her infamous fur-lined spoon, saucer, and teacup (originally entitled “Fur for Breakjast”). Man Ray, in his allusions to the poetry of objects, regularly dealt with provocative sexual themes. A seminal literary trope of the Surrealist movement, Lautremont’s image of “the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella,” echoes throughout Randolph’s explorations of medical operations and experiments. The representation of the all-too-weak human flesh at the mercy of strange machines and methodologies is an extension of Randolph’s concerns with how nature interfaces with the rapidly developing technologies of the information age. And she readily acknowledges her love of Rene Magritte, an artist whose Surrealist depictions include not only a timid bowler-hatted man but also overtly sexual signs and symbols; Randolph admires his work as “about ideas.” 1

fig. 3

Frida Kahlo,

The Little Deer, 1946

Oil on canvas

8 7/8 x 11 7/8 inches

Collection of Carolyn

Farb, Houston, Texas

When Andre Breton’s Surrealist tenets alighted in Mexico, they coalesced with an already powerful native sensibility captivated by magic and visionary states. Randolph’s art certainly must deal with the shadow of Frida Kahlo, but Randolph had firmly established her themes and techniques independently of Kahlo’s direct influence: until 1978 she was not even aware of Kahlo’s work. When she first experienced a Kahlo painting, Randolph says she felt as if she had “been knocked across the room;” Certainly, stylistic and thematic concerns resonate between the two artists.

Beyond the visual arts, one of Randolph’s strengths as an imagist is a serious and diverse engagement with numerous other disciplines (a complicated topic that can only be noted in the present text). Well-versed in psychology, sociology, and history, especially feminist studies, she creates paintings that are unique clearinghouses for the juxtaposition of intellectual themes and explorations in which the highs of aesthetic theory and lows of popular culture easily coexist. Randolph, both an avid reader and cineast, has acknowledged a diverse range of inspirations from other art forms: literature ranging from author Edgar Allan Poe to science fiction writers like Octavia Butler (“Dawn”) and John Varley (“Press Enter”); and films from directors George Romero (“Night of the Living Dead”) to Ridley Scott (“Blade Runner”).

Within painterly traditions, Randolph cites her fascination with the tenets of Renaissance painting, works by such artists as FraAngelico and Sandro Botticelli. An especially redolent technique of the Renaissance is the treatment of drapery (see fig. 5). The unveiling light and enclosing shadow of the fabric forms became a metaphorical mode that enabled Renaissance artists to introduce sensual concerns into their work even as they depicted religious subject matter. Randolph has extended this metaphor in numerous paintings where flowing drapery, clothing, fabric, or bed linen have taken on overtly labial forms. This fascination with enfolding and unfolding at its most basic evokes both the penetration of sexual intercourse and the dilation of birthing. The crease and flow of fabric, which convey these associations, also indirectly imply the moment of genesis, the emerging from womb into the wonderment of experience.

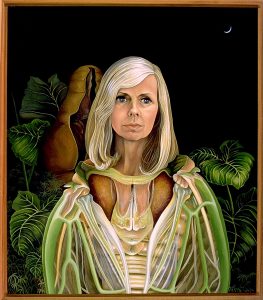

fig. 6 Me Waxing, 1985

Oil on canvas

31 x 27 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Thus, Randolph’s paintings often deal by extension with the theme of dawning human awareness. In one of her most remarkable self-portraits “Me Waxing,” 1985 (fig. 6) Randolph’s face emerges into a lushly rendered natural landscape from the molting shells of a cicada, a process that signals the ecological origins of human responses. In “Alone in the Wetlands of Desire,” 1993, a woman lies on her bed, the private locus of much human sexuality, in an equilibrious state, suspended between quiet repose and erotic reverie. The bed itself is a melting flow of undulating forms that simultaneously evoke rippling bed linens and cascading water; it floats in a primordial swampland, the cradle of life. The phallic form of a distant egret suggests the presence of the male animus. Here Randolph describes another avenue to awareness, her desire–couched in specifically feminist terms, removed from an existing culture predominantly described by men–to return in her work to a state representing the origin of life and, by extension, the roots of cultural development. By returning in this painting to a primordial wetland, she hopes to free herself and her audience to reinvent a culture and myth unfettered by previously inbred–and for Randolph unacceptably freighted–responses.

Given Randolph’s fertile base of sometimes surreal elements and her complex metaphorical references, it is perhaps startling to realize that in any given work she is also emphatically dealing with portraiture–and portraiture in its most traditional sense. Randolph’s works are almost always populated with depictions of actual people: her friends, associates, and contemporaries. They may appear as themselves or in marvelous guises, but they are uniformly recognizable as actual people. Similarly, she returns regularly to the self-portrait.

fig. 5

Sandro Botticelli,

The Annunciation,

c. 1489-90

Tempera on wood panel

59 x 61.5 inches

Uffizi, Florence

Much as Renaissance artists often assigned the actual visages of patrons, peers, or themselves to the subjects in their paintings, Randolph builds her representations from personal associations. In her studio, a motley bulletin board covered with fading snapshot portraits reveals the photographic source of many of her posed figures, but the success of her characterizations is based more on an innate understanding of human foibles. In a process akin to the development of character in literary works, the richly observed agglomeration of humankind in Randolph’s paintings is infused with a specificity that provides a compelling entryway to the artist’s morality plays. The acuity of her observational details has the effect of connecting the viewer via a recognizable, accessible human personage to the scene depicted, a scene that may otherwise reveal only an enhanced hyper-naturalism or a purely dreamlike environment. Thus, Randolph has devised a useful method for grounding the ethereal by means of the actual, allowing the viewer access to her vision.

While one can often find Randolph’s humankind experiencing hope, enlightenment, or empowerment, her figures invariably are surrounded by a landscape of impending gravitas. In many recent works, this mood is set by an encompassing black void, which envelops the depicted personages not only in astral environments but also in seemingly interior spaces. This mood dominates paintings such as “Yesterday Inventing Tomorrow Today,” 1996, where she and her husband, Bill Simon, with close artist friends Ed Hill and Suzanne Bloom are depicted grappling with technological implications for human thought and actions. Making eye contact with many of Randolph’s portraits can convey not only a sense of awe and wonderment, but also one of melancholy. This emotion evoked because the portrayed are often caught in a moment of serious reflection; more precisely, they seem poised between shifting, sometimes threatening, forces. Sad resignation coexists with positive contemplation.

Bending the conventions of portraiture, Randolph has executed a riveting combination of metaphor and image based on historical events in a richly evocative series of small portraits called “The Ilusas,” 1992-94 (figs. 14, 15, 16) 2. In seven-teenth-century Mexico, a diverse group of women that included widows, orphans, and prostitutes banded together outside the patrimony of church, state, or marriage. Using their bodies in exotic rituals, they vomited blood at will, simulated lactation, or smeared themselves with menstrual blood, often regressing into infantile behavior or moaning in orgiastic ecstasies. Defiantly challenging the Catholic Church and the Inquisition by symbolically performing private events of femininity in very public places such as the Zocala, they were among the first women from the Amcricas to physically commandeer a public forum. They did not explicitly embrace the Devil, but on the contrary, claimed to speak with God. Therefore, the Inquisition (male guardians of a matriarchal system of devotion to the Blessed Virgin who cruelly directed vengeance primarily against women) could not annihilate the possessed women as witches; instead they chose to ostracize them as “Ilusas” (or deluded women). The “Ilusas” turned this damnation to their favor, flaunting their “madness” in recalcitrant acts of empowerment.

fig. 7

Annunciation of the

Second Coming (detail)

Oil on canvas

68 x 56 inches

Courtesy of Richard

and Janet Caldwell,

Houston, Texas

Randolph (herself an active participant in a defiant feminist drum corps) seized on the notion of the “Ilusas” as a means of expressing her own cultural liberation. Embracing the historical idea of these “mad” women, Randolph developed a means of associating her modern sensibilities with this obscure cult, in the process validating both the actions of her remotely associated cultural ancestresses and her own sensibilities. Exploiting her inclination to let actual people portray the roles in her paintings, she dramatically transposed the actions and ravings of the historical “Ilusas” onto portraits of a group of contemporary women associates and onto her own self-portraits. The artifacts of this transposition, the small paintings themselves, are among some other most accomplished and intriguing recent works; for modern viewers, they carry a primal rage that rehabilitates the spirit of the “Ilusas.” Rigorous primary works, they also comprise the artistic residue of a complex intersection of metaphorical language and historical precedence, the very act of their painting allowing both the painter and her audience to look at the world anew.

Randolph brings this theme of empowerment and resulting enlightenment from the historical past to the technological present in her 1996 painting “Annunciation of the Second Coming” (fig. 7). Borrowing the traditional setting of a receding architectural perspective and distant mountainscape, the artist inverts key iconographic elements of Christian Renaissance Annunciation scenes. Gabriel, the male archangel is displaced by a woman, who is not addressing the Virgin but rather faces the viewer. The angel’s startled expression seems balanced between disbelief and ecstasy. In a further transformation of established representation, the standing figure seems to represent the coming Savior himself transformed into a female figure; composed of silicon chips and data, she represents a cautionary harbinger of the dangers of the information age. A floating strand of DNA hints that chance and natural selection processes have been subverted by male-dominated traditions of artmaking, iconography, and criticism. Randolph’s refrain here, as with “The Ilusas” series, is the substitution of a new matrix of metaphorical representation that demands inclusion and equality–a call in this pivotal historical moment to see with fresh eyes the advent of the next millennium.

NOTES

1 Unless otherwise quoted, quotations are from interviews with Randolph, August and November, 1997.

2 My analysis is aided by reading a transcription of Randolph’s slide talk, “The Illusas (deluded women): Rep-resentations of women who are out of bounds,” presented at the Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, November 30, 1993.