Essays

Acts of Faith: Politics and the Spirit – Essay from Exhibition Catalog

by Lucy Lippard

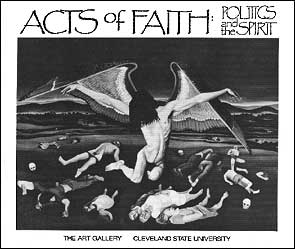

MERCIFUL ANGEL

oil/canvas, 20″ x 26″ 1986

Cleveland State University Art Gallery, Cleveland, OH, 1988

Let me say at the risk of sounding

ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is

guided by great feelings of love.

–Che Guevara

The political and the spiritual, like art itself, are fundamentally moving forces, acts of faith. If we are ineffective in these areas, we are not moved; we stand still, and the status quo is our reward. The artists in this show remind us that there are no contradictions between politics and the spirit except those artificially imposed in societies that rule by division. Of course they, the political and the spiritual, affect in different ways, but a head in the clouds need not preclude feet firmly on the earth, nor eyes and a voice with which to bear witness.

At the vortex of these two forces lies a renewed sense of function, even a mission, for art. These artists share little in stylistic terms, but they have in common an intensity and a generosity associated with belief, with hope, even with healing. Few, if any, would call themselves “religious” in any institution-alized sense, and few could deny that they are guided at least by vision with a small v. Some of them are activeists, some hang out on street corners with people both like and unlike themselves, and some don’t look too often out their studio windows. But in all of this work there is a sense of history happening, unfolding the stories of the North American Disappeared.

There is an urgency to politics that is balanced by the longer, deeper views of the psyche. Politics insists on time; spirituality denies time as we know it. All art is supposed to be “spiritual” on some level, and all art is supposed to be separated from the “political” on any direct level. Yet in an art world notoriously short on morality and morale, the introduction of both elements could be crucial. The integration of esthetic and social Integrity with a critical sophistication and with such old-fashioned sentiments as love, conviction, and accessibility is more likely to produce “new” art than new manipulations of the picture plane or “new” appropriations pulled out of the top hat.

For some time now, only feminist and the cultural left have dared to embarrass their viewers with a positive passion. It’s easier to be didactically disengaged, ambiguous, ironic, self-deprecating, or analytical from a dis- tance. Involvement and activism are difficult and often painful. The artists in this show have challenged this double taboo. The fact that many of them are people of color, of mixed race, and/or have chosen to work in cross-cultural situations is no coincidence. They are privileged in their access to more than the dominant culture, if underprivileged in view of the racism and ethnocentrism that assimilates their cultures and often denies them access to the mainstream.

As the population of the United States confronts the invigorating possibility of becoming a truly multi-cultural society, conservatives are digging in their heels with immigration found laws and English-only laws and other reflections of xenophobia–fear of the Other. Art now has the chance to be an affirmative action. It has become abundantly clear over the last decade, espe-cially to women and others isolated by their “otherness” that a concern with audience, context, and the social function of art opposes the so-called norm of an isolated and alienated art that is either above it all or below it all–“out of it,” either way. There is a growing sense that racial, political, and sexual outcasts from the dominant culture are simply turning away from it–not only in bitterness and anger, but also in profound disinterest in the value system and the incestuous games played there. Facing outwards, into the world, the view is different, and it’s often mythic, as well as politically based. The unfamiliar images and symbols buried in cultures not our own offer fresh ways of seeing the world, and art.

Lynn Randolph was led into her Angel series (Merciful Angel, Surviving Angel, Despairing Angel, Vigilant Angel, Angel of the Mourning Mothers) through activism on Central American issues. These spirit guides evade religious stereotypes; they come to us in all colors, pleading Intimately with viewers for a responsible spirituality. The paintings are small, dark, heavy with pain, and pay homage to the santos and retablos of Latino America. In Viral Eclipse, Randolph’s more typically glowing, meticulous and visionary realism parallels the care and caring with which she watched a close friend die of AIDS, as though the painstaking detail could exorcise the anguish.

It’s all about transformation–a much overused word that nevertheless is irreplaceable both for the self and for society, or self towards society. The artists in “Acts of Faith” work from a certain innocence, and a certain outrage, mediated by political consciousness and a sense of humor. Transcending without denying the barriers of class, race, and gender, they support Emile Durkheim’s contention that society itself is a creative power and the origin of religion, that only the Intensity of collective life can awaken individuals to new achievements.

Lucy R. Lippard

____________________________________

Excerpts from the catalog for the exhibition, Acts of Faith: Politics and the Spirit,

Art Gallery, Cleveland State University, 1988