Essays

Moving Pictures

by Marilyn A. Zeitlin

Catalog essay from Millennial Myths: Paintings by Lynn Randolph, Arizona State University Art Museum, 1998

Lynn Randolph situates her work at the nexus of the familiar and the unknown She conceptualizes that territory and formulates visual metaphors to suggest a narrative that precedes and follows the moment to which she privileges us in the icon of the painting. She allies herself with the role of the artist as a maker of images for what may be invisible; as yet unknown, or strictly theoretical. The work, informed by Randolph’s understanding of contemporary critical theory, the history of science, feminism; and the history of art, sets forth a narrow platform of safety and of familiar ground only to rapidly catapult the viewer into conjectural space.

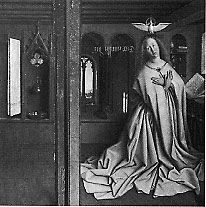

Randolph brings to her work a style she calls “metaphoric realism” that hovers between that of Jan van Eyck, 1 as seen in such works as “The Ghent Altarpiece,” 143 (fig. 9)2 and science fiction–a way of depicting the future; the inner workings of body and mind, and allegories of the present in a manner that is vividly specific. The work is disturbing; and intentionally so. Randolph, despite her deliberate constructing of beauty, does not set out to comfort the viewer. She conveys her own confrontation with the postmodern world and her predictions for the future with a toughness that is acceptable only because of the beauty of the painting.

fig. 8

“Transfusions” (detail), 1995

Oil on canvas, 48 x 60

Her work is always readable; especially to a generation literate in new technology with its acknowledgment and embrace of the reality of the present. The work is never meant to be abstruse, but rather to communicate an idea or vision to which the viewer is compelled to respond. And, beyond the first impact; the work never closes itself off from association and broad interpretation. Her freewheeling approach to borrowing–both stylistic loans and iconographic ones–is in the mode of post-modernism as well. Randolph is entirely comfortable collaging periods and styles, capturing the limpid color and intensely specific image of a Van Eyck, for example, then applying them to convey contemporary content. In fact, the two artists seek to achieve the same end: to depict another reality in a completely credible way.

Metaphor and Myth

One of the great contributions of critical theory to contemporary thought is the dismantling of the “grand narratives” of modernism and, indeed; of Western thought. These grand narratives incorporate societal assumptions so pervasive as to be invisible or, worse yet, to seem inevitable or “natural.” Within these grand narratives are embedded such assumptions as male supremacy, the place of humanity at the pinnacle of a great chain of being; and white supremacy–the last usually politely masked as the superiority of Western civilization, particularly in its function as the yardstick against which all others are measured. Who are the great masters of world art? Michelangelo. Leonardo da Vinci. Picasso. Perhaps Diego Rivera might sneak into this pallid crowd. What is wrong with this picture?

fig. 9

Jan van Eyck, “The

Ghent Altarpiece (detail

of closed state, “The

Annunciation), 1432

Oil on wood

135 x 172 inches, overall

Cathedral St. Bavo,

Ghent, Belgium

These narratives are encapsulated in mythology; a system of thinking that is perpetuated, first through the oral tradition and later in written form, as stories passed from generation to generation. But like all entertainments, these are also lessons, sets of rules, with implicit definitions of normalcy. Think of Odysseus wandering the world, seduced by sirens, while Penelope stays at home forever weaving, each night unraveling her day’s work to stave off the sexual advances of her husband’s enemies. He has the adventures. She stays at home performing a labor-intensive and ultimately useless task while preserving her virtue–as his property and, in turn, as a symbol of his power: she herself is perceived as powerful only as his wife. This story is not only diverting, but it describes Penelope’s conduct as normative. The myth forges a role model that reflects a socially ordained order, rewarding Penelope and all that emulate her for loyalty and chastity.

Mythology does demonstrate deviance, but it always seems to be clear that the alternative described is exceptional even if valorous, and not to be tried at home. Athena, from her genesis, out of her omnipotent sire, Zeus, from whose head–or thigh, which seems closer to the mark, really–she sprang full-grown, is ready to do battle. Like Joan of Arc, she offers a legitimate alternative female role. But both Athena and the Maid of Orleans are regarded as special cases in contrast to Penelope’s model-of-virtue norm. And in the case of Joan, she wears her hair suspiciously short.

Interestingly, the same contrasting pair of female role models appears in the classic Indian epic “The Mahabarata,” in which the domesticated Sita is contrasted with the warrior-woman Sri Kandi. Significantly, few female patterns are suggested between these two extremes, and there is no doubt that Sita is the ideal, with Sri Kandi on hand to pick up the deviants and so keep them within socially accepted bounds. Too much of a tomboy, she is put on the battlefront where she can be useful, but you would not want her outside a highly disciplined environment lest her deviance necessitate change in the social structure.

This choice of myths is apposite to Randolph’s exhaustive research in feminist theory. Her knowledge and reading of the issues are both passionate and deeply analytic. Randolph is not party to the cssentialist school of feminism that attempts to redress the gender imbalance by declaring all women goddesses. She sympathizes with the approach to feminism that regards the differences between male and female–and among women themselves–as a product of social conditioning, yet she also acknowledges and celebrates what is special to femaleness, vividly portraying female sexuality and its potency. This attitude is reflected in the ongoing conversations and mutual influencing of Randolph and Donna J. Haraway, the distinguished radical biologist with whom Randolph has collaborated. Finally, Randolph’s feminism is linked with the global view’s of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, for whom feminism denotes not simplv the analysis of the role of women and the commitment to deconstruct assumptions that keep women in their places, but also a study and examination to find the violence inherent in treatment of all oppressed groups and species: the poor everywhere as well as children, animals, and colonialized subjects.

Randolph, then, does not discard the notion of mythology as a means of conveying social norms, but she has some serious issues with the standard canon. Undaunted, she undertakes to forge new myths, ones that may draw from the canon but that also press forward to forge new images of women–and of human beings altogether.

![fig. 10 "La Mano Poderosa" [The Powerful Hand], 1957 Oil on Masonite 20 x 14 inches Courtesy of David Connelly, St. Petersburg, Florida](http://www.lynnrandolph.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/47_lg-208x300.jpg)

fig. 10

“La Mano Poderosa”

[The Powerful Hand],

1957

Oil on Masonite

20 x 14 inches

Courtesy of David

Connelly, St. Petersburg,

Florida

This work, in simple terms, expresses Randolph’s persistent optimism. Having followed the breakup of the Enlightenment tradition to its apogee in modernism, Randolph acknowledges the exhaustion of that train of thought. Yet she is not prepared to jettison the utopian ambition it embodied and is just quixotic enough to consider alternatives to the nihilism toward which postmodernism seems to lead us.

In a sense, all her work is an inquiry into what it is to be human, exploring boundaries both with technology and with other species. Among the sources for Randolph’s new mythology are her honest assessments, from an informed political and ethical stance, of the post-modern condition. The utopian models and ideologies of modernism never

really dismantled the old canon. In fact, modernism seems to have preserved Western traditions of sexism, racism, and colonialism intact within the analysis that forged its utopian models. Socialism may have at- tempted to forge a New Man, but the gender restriction in those words alone tells much about who is left out of the ideal world thus proposed. Randolph creates alternatives that face up to the present reality with its pervasive violence, not only at the level of wars and disintegrating societies, especially in the Third World, but also in the cities, in schools, within the family, and within the body. The subtler violence of racism is an issue Randolph never can let rest, and she returns to it in many different ways.

Randolph finds sources for content in a broad range of disciplines. Among these are contemporary science, which she uses to presage the evolution of humans, animals, and technologies into new life forms, placing her visionary images into contexts that include the urban present, the nebulae. the biological microworld. and a glimpse of Armageddon in our own backyards. Randolph hardly takes a Luddite position–condemning technology for ruining what is natural–since she, of course, doubts the rigidity of any “natural” order of things. Yet neither does she fall into what she dubs “technophilia,” adoring new technology for its own sake.

Randolph brings together ideas of art, science, and technology using a vivid visual vocabulary. Unlike much art related to technology, this work focuses on scientific thought and visions of the future–both utopian and dystopian–rather than on special effects employed to demonstrate the capabilities of a given hardware or to over-whelm the viewer with sensation. In fact, the innovation in the work is not technical: it is in the ideas of contemporary art and science that the artist explores.

Randolph filters information through her own process of assimilation. Often the information, as the viewer encounters it in her work, is imbued with double–or triple, or more–emotional vectors. An image can be ghoulishly threatening and at the same time funny.

![fig. 11 Remedios Varo, Creacion de los Aves [Creations of the Birds], 1957 Oil on Masonite 21.25 x 25 inches Private collection, Mexico City](http://www.lynnrandolph.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/varo.jpg)

fig. 11

Remedios Varo,

Creacion de los Aves

[Creations of the Birds],

1957

Oil on Masonite

21.25 x 25 inches

Private collection,

Mexico City

One can see the impact of early Renaissance masters such as Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi on those canvases in which she engages contemporary and future-oriented issues. In the style that she calls “metaphoric realism,” Randolph presents a visionary reality in vividly tangible terms, giving the work an intensity and edge that satisfy the human longing for images of the unknown. Technically, like both Italian and Flemish painters who were engaged in portraying a vision in palpable terms, Randolph paints in a hard style. She uses black to offset the richly colored figures and landscapes, eradicating areas to eliminate any distraction from the drama recorded in the iconography. The black, too, creates a dreamlike ambience, a background against which images cross, “floating in the unconscious, out of the abyss,” as well as a distinctly theatrical staging, an effect reinforced by the persistent frontality Randolph most frequently employs. The vividness of the painting startles the viewer since the content is a fusion of a particular vision as reflected in contemporary critical theory with the contemporary culture it analyzes, all presented with a sense of both the grandeur and, oddly enough, the familiarity of ancient myth.

The Body Technologized

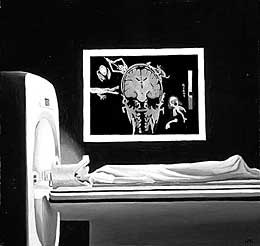

fig. 12

Imeasureable Results,

1994

Oil on Masonite

9.5 x 10 inches

Courtesy of Volker

Eisele, Houston, Texas

Since 1962, when Thomas Kuhn published “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” there has been a gradual integration of the study of history, philosophy, and the sociology of science. Yet the process of demystification that grew out of what came to be called “science and technology studies” was still conducted within the parameters of scientific biases, and among these are embedded racial and gender biases. Further, the cloud of awe that envelops science for its access to “truth” also elevates an elusive transcendent realm of objectivity. The work of scientists, philosophers, and historians of science in the past thirty years has paralleled, or dovetailed with, that of theorists of cultural studies, art critics, and artists articulating the postmodern condition. A nexus of the two–the cultural and scientific postmodernists–occurs in questions that concern the body, the envisioning of a future for humans and other species, and the relationships that exist among human beings, other living creatures, and technology.

fig. 13

Self-Consortium, 1993

Oil on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Courtesy of Jennifer

Gill and Paul Roberts,

Palo Alto, California

Long before the body had become the pervasive issue in art that it is today–before cyborgs were offered as the alternatives to goddesses of essentialist feminism–Randolph was painting images of women fused with an-imals or with machines, female figures with the strength–in part derived through their sexuality–of mythological deities of both past and future.

Now, with medical procedures that can replace vital organs with those of an unknown or animal donor, or with mechanical replacement parts, the boundaries defining what it is to be human are under pressure to expand. This is, in a sense, what is meant by the end of humanism. “Human” is not questioned as the pinnacle of the chain of being, but it has become a blurred category. Randolph is fascinated by this blurring and conveys in works such as “Transfusions,” 1995 (fig. 8), the power of this process. In this painting, bats are equated with an intravenous line, and the exchange of bodily fluids hints at both trans-species exchange and eroticism. It has an underlying humor in it, with its references to Nosferatu and vampirism. The occult is suggested, and a sense of ecstasy as well. While an indifferent scientist watches remotely from behind his console, which looks like both a television set and a puppet theater, the female figure writhes in an ambiguous gesture of pain and transcendence. “The Laboratory / The Passion of OncoMouse,” 1994 (fig. 20), in contrast, shares none of the glee of “Transfusions.” Instead, Randolph portrays the little subject of scientific manipulation as a martyr, complete with a tiny crown of thorns. The mouse-woman is surrounded by voyeurs–scientists observing her in the isolation of the laboratory. Both these paintings contain humor–or they would be intolerable–but they also take a serious swipe at conventional scientific objectivity, which so often can remove itself from philosophical questions of identity and ethics, leaving the subject in isolation.

Randolph repeats the format of isolating a subject / victim in a laboratory in “Managed Care,” 1996. A nude man writhes on a gurney. His open mouth and hand suggest a kind of sodomy, while the angle of the body relative to the picture plane recalls the dynamic foreshortening of Rosso Florentineo. 3 His supine helplessness also evokes Titian’s “Rape of Europa,” c 1559-62, 4 as Titian’s and Randolph’s models each raise a knee to protect the genitals. The exchange of gender in the victim in the work of Randolph would not be an accident. We know they are both doomed–to rape or the surgeon’s knife, seemingly equated in Randolph’s analogy. Her appropriation of the myth of Europa, whether intentional or instinctive, to elucidate contemporary medicine is precisely the forging of new mythologies that is at the heart of Randolph’s work.

Randolph’s skepticism about the practice of medicine does not preclude her awe at the knowledge and creativity it embraces. Nevertheless, in “Immeasurable Results,” 1994, (fig. 12) which shows the medical imaging of a brain scan above a faceless and insensate body, the real workings of the brain escape detection: immeasurable.

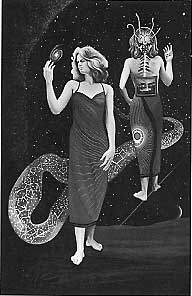

The question of cyborg transformation is glamorously treated in “Self-Consortium,” 1993 (fig. 13). Using the traditional device of continuous narration, Randolph presents a figure and its clone from the front and back, respectively. It is as if we see first the front and then the back, of a model on a runway. But what is revealed is the circuitry that powders the clone. The two are linked by a galactic ribbon, evoking the cosmic scale and power inherent in both nature and the technology.

fig. 14

Wounded, 1994

Oil on Masonite

14.5 x 10.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

fig. 15

Excessive Absorption,

1993

Oil on Masonite

14.5 x 10.5 inches

Courtesy of the artist

fig. 16

Embrace by Fire, 1993

Oil on Masonite

14.5 x 10.5 inches

Courtesy of Macey and

Harry Reasoner,

Houston, Texas

The Body Eroticized

Randolph’s relationship to the body is only partially reflected in her work concerning medicine and technological trans-formations. She is particularly interested in the female body, going beyond the cliches of its place in the male gaze, or as a commodity, erotic only for the benefit of another, usually a man. Referring to the “Ilusas” of the Spanish Inquisition, Randolph has painted a series of small images of women experiencing private sexual ecstasy. They are depicted alone, each framed in a Mexican hammered tin frame like those used on retablos for images of saints. Randolph thus elevates this moment of acute sexual experience above the sordid by framing it as sacred. Sexual and religious ecstasy has been famously conflated in Gianlorcnzo Bernini’s “The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa,” 1644-52. 5 Randolph’s “Ilusas,” however, are not nuns (figs. 14, 15, 16). Yet they do seem to span two worlds, placed in contemporary settings that reverberate with Renaissance imagery. In “Venus,” 1992, Randolph sets the figure in a gray ground with darker gray clouds at the top. From the clouds depends a pink scallop shell that is a hallmark of Renaissance painting and architecture, a symbol of purity. Formally, it provides the perfect form for creating a niche, which is how we most frequently see it: as a canopy over the Virgin. It is also familiar to us turned up and serving as a platform for Sandro Botticelli’s figure in “The Birth of Venus,” c. 1485. 6 But Randolph’s Venus is not a virgin, proven by the lactation that she aggressively displays, nor is she the modest Venus of Botticelli who with one hand partially covers her breasts (thus calling our attention to them) and with the other holds a hank of hair in front of her genitals. Randolph’s Venus instead returns the male gaze with a directness that challenges any authority beyond her own. She is a powerful female figure looking us straight in the eye.

By conflating the iconography and symbolism of the Virgin and Venus–who are, after all, sisters under the skin–and projecting these associations on a figure painted from a life model, Randolph forges a contemporary myth, grafting the power of its precursors to a meaning that consolidates a feminist position: the painting acknowledges female potency in a figure with physical strength and erotic power under her belt.

The dark side of sexuality is a subject that Randolph docs not evade. Before time and before subjectivity, before social organization, sexual relationships linked human beings: after all, and despite the “superior” brain and culture and technology, we are animals subject to instinctual drives.

Randolph has been using specific models–usually her family and friends–for a long time. She expresses love through her detailed representations, which give the paintings a powder akin to Surrealism. One of her influences is Rene Magritte (like many Houston artists, Randolph is nurtured by the treasures of The Menil Col

lection, which has extensive and outstanding Magritte holdings). The hard-edged style used by both Magritte and Randolph to convev the visionary is like dreaming with one’s eyes open.

Randolph has read widely and with her critical faculties engaged. What she has learned, what she thinks about it, and what she sees as a result of her absorption of infor-mation and theory, strained through her personal world view, are distilled and projected in her paintings. These are often apocalyptic, prophetic, and frightening, but they are also irreverent and witty–and ahvays passionately felt.

Randolph’s work is often mistaken for the output of a much younger artist (she is in her mid fifties) because it is so alert to contemporary thought, so full of readings of popular culture, and–almost by coincidence–so compre-hensible to the cyberculture generation. The influence of late medieval and early Renaissance painting on her style, once it is applied to a visionary imagery of the future, gives her work the punch of a J. G. Ballard novel or Thomas Pynchon’s “Gravity’s Rainbow.” The vision hovers between the films of Andrei Tarkovsky and Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner.” In fact Rachel in “Blade Runner,” a cyborg with the emotional capacity for fear, love, and confusion, personifies [sic] much of Randolph’s notion that the changes that science will bring need not be regarded as invasions of mind-and body-snatchers but possibly as the creation of the next “human” model.

Randolph often places her figures in a “pre-social” setting. She carries a vision in her mind of the primordial desert of Big Bend in southwest Texas, a place in which the extra-ordinary can occur, one where human scale is overwhelmed by the landscape. She also works within a charged celestial realm: the sky populated with nebulae. In “La Mestiza Cosmica,” 1992, a Latina woman stands on the earth and, with a gesture that recalls that of a Buddhist deity holding