Essays

Excerpts from The Vocation of the Artist

by Deborah Haynes

The Vocation of the Artist, Deborah J.Haynes,

Cambridge University Press, 1997

Part I. Preliminary Issues

Chapter 3 / Vocation

p.30-33

The idea of a calling is illustrated in Remedios Varo’s 1961 painting, The Call. The central figure, luminous with radiating filaments of light, wearing and carrying alchemical vessels, her hand in a gesture similar to a Buddhist mudra, leaves behind those half-awake, half-conscious, people who frame her. They remain caught in and part of an otherworldly sanctum, whose windows seem to open into nothingness. Labial walls simultaneously hold the figures in and seem to imply the possibility of their emergence. The figures’ feet and heads, in dull shades of brown, seem ready to emerge. Bright orange, the main figure has fully emerged from the dark alcove behind her. Her hair is connected to a planetary orb; her feet seem to illuminate the patterns on the floor over which she walks. The figure leaves behind the state of sleep that mystics such as Gurdjieff thought was our normal human condition. The sense of a “call” is clearly depicted, but toward what is this figure called? Perhaps she is making a personal journey towards wholeness and enlightenment. She is initiated into the process of spiritual becoming, although how or why is unclear. Who calls? We cannot know.

* * * * *

As I turn now to the concept of vocation, these eschatological concerns take another form. Our work matters. If the ecological crisis is a crisis of the whole life system of our planet – and I think that it is – then it calls into question all of our work in the world. “The ecological crisis today suggests to many observers that there is no future for our species on this planet and no future for the planet so long as our species refuses to change its ways. But this is where vocation enters – a voice from the future calling persons to believe in a future.” Belief in the future is not about dogmas, but it means acting as if there will be a future. A primary mode in which most of us act is by working in the world. Thus, my claim: our work matters.

This chapter is not an attempt to define work transhistorically or as a universal category of human experience. This would be extremely difficult, because the work is so diverse. Work is also so ordinary, so close to us, so interwoven with our ideas about who we are and what we might become, that to try to generalize about it would be folly. The nature of work is changing drastically with the development and application of newer technologies. There are also presently many crises concerning work around the world, crises of child labor, unemployment, discrimination, dehumanization, the exploitation of workers, and the destruction of the environment, to list but a few.

We work because we are human, but the meaning we attach to that work varies tremendously. The idea of work evokes a series of terms and related concepts. “Work” is similar to and sometimes synonymous with “vocation,” “labor,” “toil,” “drudgery,” “chore,” “job,” “gainful employment,” “action,” and even with the idea of an “opus.” Each of these terms has its own valence. Vocation is perhaps the most complex term, as I discuss in what follows. Toil, drudgery, and chore all identify negative demanding activities that most of us would rather not do. Job and gainful employment are more positive and life sustaining, though often viewed as a necessary unpleasantness. Opus, in the sense either of a creative work or of a lifework, as Carl Jung used the term, also has a positive meaning. A further significant distinction separates labor, work, and action. We labor to meet our everyday needs. WE work to create the world of things. But action, as we shall see, is born of another set of values more related to my ideas about vocation.

Artists, like other cultural workers, seldom think of their work or describe it in terms of vocation, although I suspect that many feel “called” to do it in some general way, like the figure in Varo’s Call. My purpose here is to provide a background or foundation for reconsideration of what it might mean to speak of the vocation of the artist. To this end, the chapter has a specific philosophical goal: to trace historical notions about vocation and work in influential writers such as Martin Luther, Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and Hannah Arendt, describing how the process of increasing secularization has affected views of work in the world, the purpose of work, and problems such as alienation. Beyond this, I want to reclaims a sense of vocation as action in the world, a calling that must be chosen with a sense of determination and commitment.

Marcuse thought that the Beautiful resonates with originality, with strong formal qualities, and that it allows complex meanings to evolve, rather than be obvious. This is certainly in keeping with the ideas of artists such as William Blake or Vasily Kandinsky, who believed that only through struggling to understand their poetry and art could consciousness be transformed. Many critics have not understood the subversive potential of the concept of beauty, especially when it is linked to social and political goals, as in Lynn Randolph’s paintings (Figures 31 and 32). But what of the ugly? Some activist artists, such as Nancy Spero and Leon Golub, consistently give prominence to the ugly. A major problem with much aesthetic theory is that it values only one half of the beauty-ugliness dialectic. In so doing, this theory and its supporters miss the subversive potential of the ugly as well.

Part III. The Reclamation of the Future

Chapter 10 / Visionary Imagination

p.228-230

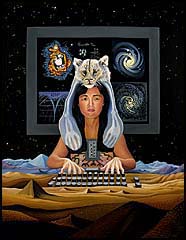

What future would the visionary imagination reclaim, and what would that future look like? Neither the paintings of Porfirio DiDonna nor the performances of Laurie Anderson enable the viewer to answer such questions. In fact, I hesitate to posit any answers at all, for it is the task of the artist who takes such ideas seriously to work out those answers for herself or himself. This conviction notwithstanding, I end this chapter with two paintings by Lynn Randolph that present imates of moving into the future: “Cyborg” (Figure 31) and “Skywalker Biding Through.” (Figure 32).

Fig. 31

Cyborg, 1989

In Randolph’s 1989 “Cyborg”, a Chinese woman not only sits at, but her hands are connected to, a computer keyboard. She links the various domains – animal, vegetable, mineral – but is herself not of them. For the figure is a cyborg, a mixture of human and machine, an expression of the latest technological possibility. Randolph’s “Cyborg” directly engages Donna Haraway’s concept. The cyborg is both myth and tool, a frozen moment in time and an imaginative reality. The integrated circuit board on its chest represents the possibility of connecting with other galaxies in the vast universe. The cyborg exists at the boundary of the animal and human realms and at the boundary of the machine and the human. It has no unitary identity. Born where automation meets autonomy, the cyborg expresses an important element of transgression. Haraway means for this border crossing to be a progressive alternative to patriarchal fantasies of the domination of nature, of woman, and of the machine. But is Randolph’s cyborg really free?

The landscape she inhabits is desolate, nowhere we know. The desolation of the land suggests a moonscape. The background is a starry night but not the familiar night sky; it is the cosmos. Directly behind the central figure is a screen, on which appear four computerized images alongside three handwritten ciphers, including Einstein’s relativity formula and a chaos theory equation. The entire image is totemic: keyboard, the torso of a cyborg, a human face, the animal head (is it skinned or still alive?), and handwritten ciphers. Northwest Coast tribes such as the Kwakiutl, Tlingit, and Haida typically carved totem poles to invoke the presence of their deities, but what is invoked here? In the background, a tic-tac-toe diagram is filled, not with Xs and Os, but with symbols for male and female. If we are creators of our own salvation, then what is suggested by this mutant creature, a creature whose actuality becomes more and more real every day?

Fig. 32

Skywalker Biding Through, 1994

Randolph’s “Skywalker” suggests another set of values about the future than “Cyborg”. Randolph had stopped painting nudes for a period of years, not wanting to participate in the objectification, explotation, and commodification of women’s bodies. Simultaneously, however, she did not and does not want to pretend that women’s bodies do not exist, thereby underlining women’s invisibility. Wrestling with the problesm surrounding gender and representation, Randolph seeks to incorporate self-love in nonpatriarchal visions. As the artist puts it: “By refusing to participate in oppositions like theory versus fiction and truth versus art, which are hierarchical, a space opens up that transforms the logic of power into new methods that interrupt, intervene, short circuit, disperse and diffract endlessly, making energy explode into a new poetics of the body which will shelter many interpretations.”

In “Skywalker Biding Through”, a nude woman strides confidently towards the viewer, pushing aside planets or asteroids, perhaps pushing aside the veil that separates the past and present from the future. Like the “Cyborg”, she inhabits cosmic space, but here the woman is center stage, the sole agent in this starry night. Not afraid of the dark, “Skywalker”s gaze, like Olympia’s, locks with ours, but she is no passive spectacle awaiting the consummation of a business proposition. She commands her space and her right to stride into the darkness and into the unknown.

Perhaps, in the end, the visionary imagination must remain open to what artists and others will make of it. Even when all master narratives have been debunked, or at least seriously thrown in to question, we still need to recognize the importance of stories. Narratives form the past, present, and future archive of human experience; and “narrative identity is a task of imagination.” “The Vocation of the Artist” should be read as a narrative containing possibilities for consideration.