Essays

A Return to Alien Roots – Essay from Exhibition Catalog

by Margaret Miles

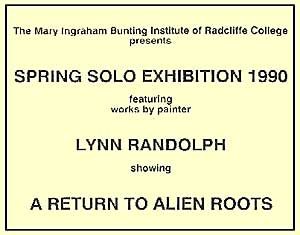

The Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1990

The Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College, Cambridge, MA 1990

Picture a tiny medieval demon in boxer shorts and a dotted green tie: picture a middle-aged woman crossing a fertile desert on the back of a huge snake: picture a young Jew writing “credo” with his own blood on a globe. These are images that disobey aesthetic conventions in order to provoke, disrupt, challenge, and heal: they are images of humor, hope, and rage, of violence and demanding beauty. Lynn Randolph’s art, a gentle, passionate, responsible art, provides a visual vocabulary which blocks the voyeuristic gaze and stops the fetishizing eye with images that are ancient and mythic yet are urgently contempory, marked by the last decade of the 20th century.This is an art that simultaneously seduces by its surreal beauty and nevertheless refuses to supply merely aesthetic pleasure. It is an art of humor and horror, an accessible public art, not an art addressed to connoisseurs and collectors. “Art is not done,” Picasso once said, “to decorate apartments.”

Randolph’s paintings achieve their power by a reduction of images to their most powerfu; motivating effects–fear and love. These paintings contradict the assumption that fear and love are opposites of the psyches just as they subvert the conventional polarization of pleasure and pain.They insist that what these “opposite” effects have in common is their power to unsettle, to move, to change–to startle the viewer into seeing and acting .The common enemy, they proclaim is, deadness– the paralysis and inertia–within North American public and private life.

These paintings name the collective evils that cause infinite individual suffering –homelessnes, hunger, United States foreign policies, disease, and religious fanaticism. In the same visual field are images of response and healing– shelter, nourisment, and flowering, fruitful abundance–images of a different power. The viewer’s first impulse is perhaps to sort images of violence and pain from images of healing, but the paintings resist that effort of conceptual control by deliberately presenting contradictory images in an irresistible cyclic oscillation. The paintings initiate and maintain a dialectic full of tensive, communicable energy.

And beauty? Randolph’s paintings are powerfully, painfully, beautiful–by Rainer Maria Rilke’s definition of beauty:

For Beauty’s nothing

but beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear.

________________________________________________________

Margaret R. Miles

Bussey Professor of Historical Theology

Harvard Universitiy Divinity School